• Have you had any formal art training (art school, private/public lessons, etc...)?

I've had only the minimal art training one receives in regular school plus encouragement from my mother who did go to art school herself. She taught me the rules of perspective when I was about ten or eleven. By the time I was old enough to apply for art school I was sick to death of the whole education system. There's very little training required in most art practice, anything you don't know can be found in books; all the rest is whether you're any good or not. All my friends who did go to art school had an awful time being bullied by idiot tutors.

• Does the majority of your work (professionally and personally) fall within the weird/horror genre, or had you created works outside of that field (fantasy, documentary, whatever)?

The majority of my work centres around the horror field although much of the Lord Horror material I've produced with Savoy we tend to regard as (very) dark fantasy. I don't trouble myself with categorisation too much, there's always a blurring at the boundaries of genres and I often like things that mix genre rather than remain within a given area. Even Lovecraft's work does this; many of his early stories are fantasy/horror, many of the later ones horror/SF. I've produced over 20 paintings for the Magic: The Gathering card game which are straight fantasy stuff, plus other CCG work. There have also been odd forays into the SF world, mainly with the (largely dire) covers I was painting for Hawkwind. I got bored with straight SF years ago whereas I can still read fantasy novels with enthusiasm, provided they're any good, of course.

• What of your work, outside of The Haunter of the Dark and Other Grotesque Visions, has been published or met the public eye in any way?

The main body of material outside the Lovecraft work so far has been the Lord Horror comics for Savoy plus various pieces of illustration. I've done eight issues of Lord Horror (another is on the way) since 1989 plus assistance on some of their Meng & Ecker and other titles. Savoy is currently putting together a series of reissues of cult books; I'm designing these and will also be providing illustrations for one of them (The House on the Borderland by William Hope Hodgson).

[A Savoy edition of The House on the Borderland never materialised but I did illustrate the novel eventually for Swan River Press —JC]

• I noticed you had done (and still do) a lot of work for Savoy. How did that all come about?

I moved to Manchester in 1982 as the city seemed to have a lot more going for it than Blackpool (still does) plus a number of friends were attending the university there so settling in was relatively easy. Blackpool is a small-town holiday resort and Manchester was the nearest big city; at the end of the '70s its excitement was defined for me by the presence there of Factory Records (home of Joy Division) and especially Savoy Books, then producing their first run of distinctive paperbacks. When I moved here, I was producing sleeve art for the rock group Hawkwind; from 1981-85 I painted 10 album covers for the group, also single sleeves, T-shirts and concert programme designs.

Within a month I met Michael Butterworth backstage at a Hawkwind gig. I knew Mike from his association with Michael Moorcock's New Worlds magazine and his connection to the whole British New Wave of SF in the late '60s and 1970s; he'd known the band for a few years but this was the first time we had met. Most importantly for me, there was also his association with Savoy.

David Britton and Michael Butterworth set up Savoy in the late '70s as an independent publishing enterprise, specialising in quality fantasy, graphics and post-New Wave SF (Michael Moorcock, Harlan Ellison, Samuel Delany, Henry Treece, James Cawthorn among others). Fortunately for me, they also ran a number of bookshops in the city and I was able to maintain contact with Mike and later David Britton by visiting the shops.

Working for Savoy came directly out of the Lovecraft adaptations I was doing. I had painted my last cover for Hawkwind (The Chronicle of the Black Sword, based on Moorcock's Elric books) in 1985. I'd decided I wanted to try something that was new and closer to my own interests; the result was my comic strip adaptation of The Haunter of the Dark which I spent most of 1986 drawing. I was disappointed that there was no decent book of Lovecraft illustrations out there (there was HR Giger's Necronomicon, of course but the Lovecraft connection is peripheral). It seemed evident that if no one else was doing it, I'd have to have a go myself; so began the long haul ... While I was working on the pages I was showing them to Dave and Mike and receiving their encouragement and, on occasion, criticism. The idea was to adapt three visually dramatic stories and package them as a book. I chose Haunter because of the focus on the church; The Call of Cthulhu had a varied, world-spanning storyline and a great ending in R'lyeh; the third choice was The Dunwich Horror. The Call of Cthulhu took 18 months to draw; as it was being completed, Haunter received its first outing in a large format edition of 500 copies, published by Roger Dobson and Mark Valentine's Caermaen Books. Halfway through The Dunwich Horror, I received an offer from David Britton to contribute to Savoy's Lord Horror comics series.

• So tell me about Lord Horror.

Lord Horror first came to trouble the world in 1989 via David Britton's eponymous debut novel. The novel recounts the exploits of the razor-wielding fascist Lord Horror, a character based on the real-life "Lord Haw-Haw", William Joyce, an English traitor who broadcast for the Nazis during the Second World War. The novel is violent, scatological, funny, gross and surreal in equal measure as it details Horror's search for Adolf Hitler through increasingly nightmarish landscapes. In 1988, while Dave was still working on the book, Savoy inaugurated an accompanying series of comics called Hard Core Horror which followed Horror's progress through an alternate history of the events of the war, with drawings by ex-Cramps illustrator and Lord Byron of the fibre-tip, Kris Guidio.

The series begins lightly, with a picnic on the grass in 1929, growing increasingly dark and disturbing as Horror encounters various leading figures of the time: Winston Churchill, Oswald Mosley (leader of the British Union of Fascists), Unity Mitford and, finally, Adolf Hitler. The fourth and fifth issues lead inexorably into the Nazi death camps; it was my task to attempt to render the horrors of the Holocaust in Hard Core Horror 5. As is stated in the foreword to the Haunter book, the drawings of Hard Core Horror 5 came directly out of the Lovecraft strips I'd been working on, as well as attempting to present 20th century scenes in the manner of Piranesi's celebrated Carceri engravings. David Britton felt that these were so successful he started immediately planning a new series, to be called Reverbstorm, which would extend Lord Horror's universe into the fictional realm of the necropolis known as Torenbürgen. Work commenced on Reverbstorm in 1990; six issues have been published so far, with a seventh due out soon and the eighth, and final, issue to follow.

• I had heard about some legal dilemmas that Savoy had run into upon the initiation of the Lord Horror series. Would you like to talk about that?

The problem here is usually knowing where to begin, like most encounters with the legal system, Savoy's travails have been long and complex. Being based in Manchester, they had the misfortune to come to the attention of the most authoritarian police chief in the country, James Anderton. Anderton's jurisdiction in Manchester lasted from the mid-'70s to the late '80s and became notorious for its endless shop raids in pursuit of "pornography" and the increasingly lunatic pronouncements of its chief officer; a devout Christian, he stated to the press that he believed God spoke to him personally and, during the initial AIDS crisis in 1987, outraged the gay community by describing gays as "swimming in a cesspool of their own making" and suggesting people with AIDS should be interned in special camps to protect the rest of society.

In David Britton's Lord Horror novel, Horror invites a local police chief called "James Appleton" to give an edifying talk on his radio show; Dave used some of Anderton's anti-gay statements verbatim, only replacing the word "gays" with the word "Jews". This didn't go down well with the Greater Manchester Police. After a shop raid in 1981, Dave had been sent to prison for 21 days for selling "pornographic books" (books, mind you, not magazines). The police raids on Savoy shops in the early '80s were monotonous in their regularity. By the late '80s things had slackened off but picked up again with terrific force when Savoy's Lord Horror campaign began. The shops and offices were raided a number of times and copies of the (limited run) novel seized. The result of this activity was that David's book became, in 1992, the first (and, to date, last) novel to be prosecuted for obscenity in an English court since Hubert Selby Jr's Last Exit to Brooklyn in 1968.

The appeal was a high-profile affair, reported in the national newspapers, with Michael Moorcock called as a defence witness and renowned freedom-of-speech lawyer Geoffrey Robertson QC defending. The ruling was overturned but the raids continued immediately afterwards; a year later David went to prison again, this time for three months. The result of these raids was a long series of trials in 1995 and 1996 which resulted in the Hard Core Horror comics being declared "obscene", the first successful ruling of its kind in Britain (various underground comics had been prosecuted in the UK since the early '70s but all previous rulings had been defeated). My experiences in the courtroom, trying to defend my work against ignorant accusations, made me realise how backward this country is in comparison to the rest of the free world.

There is still no freedom of speech defence in English law, nor is there likely to be in the near future. There's a lot of detailed information about this whole episode in the History section of Savoy's web site. Despite all this, Savoy continues, bloody but unbowed. All the above has achieved nothing save the destruction of some of Savoy's product and the wasting of hundreds of thousands of pounds of taxpayers' money. David's third novel, again featuring Lord Horror, Baptised in the Blood of Millions, is due for publication this year.

• What artists, would you say, have had an influence on where you've taken your art and why?

A big influence early on came from an unusual quarter of the album cover art prevalent in the '70s. Our local record store window was like an ever-changing gallery of surreal and bizarre images during the heyday of designers and artists such as Roger Dean, Barney Bubbles (the classic Hawkwind covers and later Stiff Records) and the Hipgnosis group. The attraction was chiefly in the imaginative imagery, I usually had no interest in hearing the records. As I scoured the library for art books I quickly realised how much of this stuff was ransacking the work of the Surrealists and artists of the fin de siècle.

Two poles of interest established themselves very quickly; one in the presentation of fantastic imagery in popular media such as book and record jackets and the other a searching through the history of art for equivalent images and approaches. I was astounded on my first visit to the Tate Gallery in London at the age of thirteen to see the massive canvases of Biblical cataclysms by John Martin, an artist I'd never heard of who seemed totally absent from the history books. Equally surprising were Francis Bacon's Three Studies for Figures at the Base of the Crucifixion, shrieking and distorted monsters that seemed to embody a rare and disturbing "otherness" that I hadn't encountered anywhere else. This quality of "otherness" has been a key thing for me over the years and it took me a long time to realise that many of the works I valued most seemed to embody it to a profound degree.

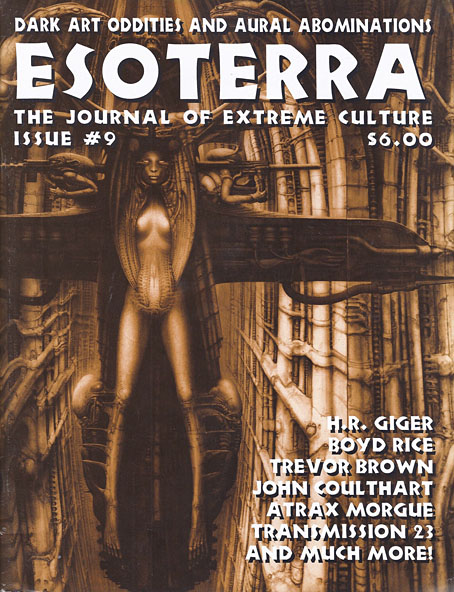

Two artists I can select whose work exemplifies this would be HR Giger and artist/occultist Austin Osman Spare, another name absent from most art histories. Put psychologically, "otherness" is really the degree of truth in some image from the subconscious that is given flesh in a work of art; this is what the Surrealists were always trying to capture and remains the thing that most interests me about the work of other artists.

Trying to keep this brief then, I think influences are those things that have altered your creative approach in some way. Artists that have done this for me would include Giger, Spare, Gustave Doré, Aubrey Beardsley, Francis Bacon, Max Ernst, Joel-Peter Witkin, Piranesi and architectural renderer Hugh Ferris, among others. In the field of comics, James Cawthorn's Moorcock adaptations and Berni Wrightson's Frankenstein were a big influence on the approach I took towards adapting Lovecraft. Reverbstorm owes a great debt to Burne Hogarth, the definitive illustrator of Tarzan; the Ononoe creatures which Hogarth invented for Tarzan to battle appear in the first Lord Horror novel and I put them and other elements of Hogarth's style into the comic series. Bryan Talbot's The Adventures of Luther Arkwright assisted enormously in showing how to convey a story using graphic narrative; the series is a textbook of comic techniques (Bryan's latest Arkwright series, Heart of Empire has just been published by Dark Horse and features a guest panel by yours truly).

• Had any other people (musicians, writers, etc ...) influenced your style in any way?

The biggest single influence from 1989 on would be David Britton with whom I've collaborated on the Lord Horror Reverbstorm series for Savoy. Dave's whole artistic philosophy of constant questioning of your work and working methods, and of the intention to push your work as far as it can go, to surprise yourself, has had a profound influence on my working methods over the past ten years. It's helped, of course, that his Lord Horror character has been one that's been a great vehicle for me to explore a wide range of subjects and techniques. Comics writer Alan Moore has also been something of an influence over the past decade, also partly due to the fact that we've ended up working together.

Aside from the obvious influence of Lovecraft and Hodgson, William Burroughs and JG Ballard have been an influence in their imaginative reach, the surreal landscapes which permeate their work and their willingness to go to extremes when necessary. Serious intent and serious intelligence are always inspiring.

• What medium/media do you prefer?

My original medium was chiefly pen and ink, with occasional forays into painting using gouache. I was happy to replace the gouache with acrylics (on canvas or board), a far more durable and flexible medium; I don't use oils. These days I'll use anything to achieve the required result. I recently produced a book jacket that began as a collage/painting hybrid, was scanned into the computer then added to using Photoshop so the final image is a digital one. Some of the art in my Lovecraft book began as pencil drawings on paper which were then subjected to considerable mutation via Photoshop again. Since computers have become capable of working at photo quality, their scope as an artistic tool has become limitless.

Digital and non-digital art have their respective strengths and weaknesses and my main interest now is working in the hot zone between the two.

• Did you use Bryce to compose all of your pure CGI artwork? If so, which version? If not Bryce, what program did you use?

I used Bryce 2.0 for the (Haunter) cover picture of R'lyeh only. I'm still intending on doing more with this brilliant program but I need to upgrade my hardware first; the final image took 26 hours to render. All other computer-related work was via Photoshop; I remain more interested in 2D rather than 3D work where computer graphics are concerned. Most 3D programs leave me cold due to the obvious artificiality and lack of texture in their results, Bryce being an obvious exception especially if the final rendering is tweaked a bit in Photoshop as the R'lyeh picture was.

• Why did you dedicate Red Night Rites 1 and 2 to William Burroughs? Did you decide this before or after the pieces were complete?

The Red Night Rites paintings (actually one painting in two sections) were intended from the outset to be "Burroughsian" due to my belief that William Burroughs is a genuine successor to Lovecraft (a controversial opinion but there it is) and I wanted to try and blend some images and elements from these two visionaries. Burroughs thought very highly of Lovecraft, a rare thing for someone which such a notable literary reputation, moreover there are numerous sequences throughout Burroughs' work that echo Lovecraft's landscapes. Let's not forget the malign invocation at the opening of Cities of the Red Night which includes the words "...to Kutulu, the Sleeping Serpent who cannot be summoned...".

You'd never get John Updike or Saul Bellow starting a novel that way. By an unfortunate coincidence, Burroughs finally sloughed off his mortal form while I was working on the painting, which explains the dedication.

• Were the Hawkwind covers your first step into professional illustrating? How old were you when you took that step?

Yes, the Hawkwind covers were my first professional work and, even though I tend to disparage that stuff now, it was very encouraging at the age of 19 to see your work in print and in record stores all over the country.

• Have you any plans to illustrate more Lovecraft stories (or other authors for that matter)? If so, what?

I certainly don't feel I've finished with Lovecraft's work although I'm not sure I want to adapt whole stories in the way I was doing before. The process of adaptation, as well as being laborious, tends to destroy the story for you, as you have to break it into its constituent parts to make it work in another medium. Since the publication of the book, the gravity of the Lovecraftian mass seems to be pulling me more in its direction once again and, having gone through the Reverbstorm series, I feel I've got some fresh perspectives on how to develop this material. It's interesting how Lovecraft's fiction is increasingly a metaphoric vehicle for viewing the world, just as much as say, the work of Kafka or William Burroughs. I'm excited by this evolution and the way that others have been adding to in things like The Starry Wisdom anthology and David Conway's Metal Sushi collection.

I feel you can contribute to this without saying "Here's another Cthulhu story"—Lovecraft himself did that first and did it best. A couple of things are already planned (for next year, probably): the illustrated edition of The House on the Borderland for Savoy (not Lovecraft, of course, but one of his favourites); we're intending that this should be as definitive as we can make it. Grant Morrison is also working on a very bizarre Lovecraftian novella for Oneiros which he wants me to illustrate. As well as this, I'm currently putting together a 2001 calendar for Armitage House using images from the Great Old Ones section of the book, plus a couple of new pieces. That is not dead which can eternal lie, as we know already.