Three Colours: Red.

Van den Budenmayer was a Dutch composer. He was born in 1755 and died in 1803. We know what he looked like from the engraved portrait that appears on recordings of his music but his first name has never been revealed. The most pertinent thing to know about him is that he never existed at all outside a handful of films, being the invention of director Krzysztof Kieslowski and soundtrack composer Zbigniew Preisner. A composer invented to enrich a scenario isn’t usually worth mentioning but Van den Budenmayer is a cinematic rarity, a recurrent presence in four different films, only two of which have any internal connection to each other. This is a common technique in literary fiction—writers love to invent details which turn up in otherwise unconnected stories or novels—but it’s uncommon in cinema.

Dekalog 9 (1988)

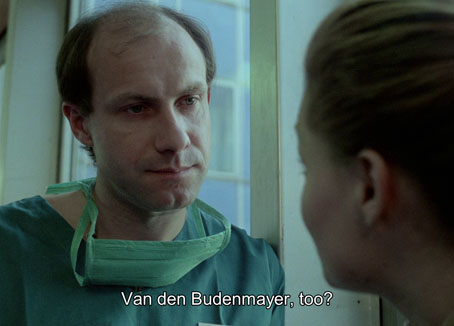

The first mention of the composer’s name occurs in the penultimate story of the Dekalog cycle, a drama about a surgeon (Piotr Machalica) who suspects his wife is having an affair. One of the surgeon’s patients is a young woman who tells him that her potential singing career has been compromised by her heart condition. During the course of their conversation she mentions favourite composers: Bach, Mahler and Van den Budenmayer. The surgeon, curious about the latter, is subsequently shown listening to a recording by the composer when the wife’s lover happens to call on the phone. The musical theme, which is reprised throughout the film, thereby becomes linked with the episode’s theme of infidelity. And since Preisner himself wrote this music, some tonal continuity is maintained with with the scores for the other films in the cycle. Dekalog was Preisner’s first soundtrack work for Kieslowski, a collaboration that continued with the following feature films.

The Double Life of Veronique (1991)

Kieslowski’s first feature made outside Poland connects his Polish years with the final films of the Three Colours Trilogy in a story that begins in Poland before moving to France. The music of Van den Budenmayer links these episodes via the lives of two more young women, both played by Irene Jacob, who share similar interests and histories. What’s notable here is that the predicament of the young woman in Dekalog 9—a weak heart endangering a potential singing career—is shared by Weronika in Poland and Veronique in France.

In the Polish sequence, Weronika passes an audition to sing in concert as a soloist with an orchestra, the composition she sings being another piece by Van den Budenmayer although we don’t know this until later on. This is where Kieslowski and Preisner’s invention is transformed from an expedient story detail to an actual character. The composition is never named in the film but the soundtrack album gives us two versions of the same piece, complete with a name and catalogue number: Concerto En Mi Mineur (SBI 152)—Version De 1798 and Concerto En Mi Mineur (SBI 152)—Version De 1802.

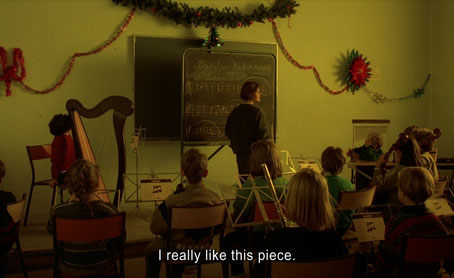

In the French section of the film Veronique is a teacher at a junior school where she takes the music class. An early view inside one of these classes shows her chalking the name of the composer on a blackboard together with the years he was alive. “He was only recently discovered,” Veronique tells the children, before she listens to them play a Portsmouth Sinfonia version of the piece we heard earlier.

Three Colours: Blue (1993)

Music is a central element in the first film of the Three Colours trilogy, with Julie (Juliette Binoche) haunted by memories of an unfinished composition by her husband, an internationally famous composer who died with their daughter in a car crash. Julie eventually feels compelled to help her husband’s friend, Olivier (Benoît Régent), complete the composition which turns out to be based on a Purcell-like funeral theme by Van den Budenmayer.

Three Colours: Red (1994)

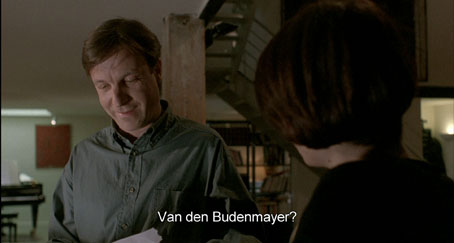

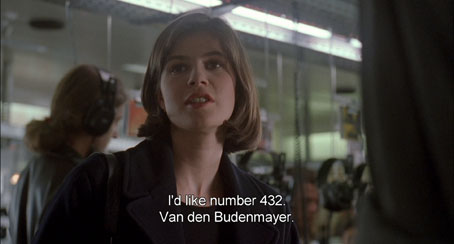

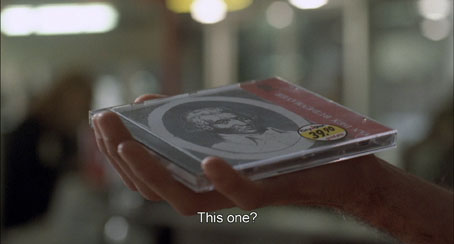

Everything comes full circle in the final part of the trilogy, with fashion model Valentine (Irene Jacob again) listening to the music from Dekalog 9 in a record shop, a piece which the Red soundtrack album has titled as Do Not Take Another Man’s Wife. This is doubly significant for a very tangled story since Joseph Kern (Jean-Louis Trintignant), the retired judge that Valentine meets, was betrayed by his girlfriend years before in a predicament mirrored by that of a legal student (and future judge) who lives near Valentine. The embittered Kern spends all his time listening to his neighbours’ phone conversations with a scanner; he also likes Van den Budenmayer’s music enough to have an album lying around although we never see him listening to it. We do, however, hear the Dekalog theme when Kern is alone in his house. (The camera lingers briefly on the composer’s portrait but it’s left to eagle-eyed viewers to make sense of that “…ayer” on the album cover.) The later scene in the record shop seems superfluous at first but I take it as a sign of the growing friendship between Valentine and Kern, especially after Valentine has melted Kern’s cynicism enough for him to tell her about his past. I only spotted the connection with Dekalog 9 after watching all these films again, also the connection between Kern and the surgeon, both of whom are victims of infidelity who eavesdrop on phone conversations.

It’s tempting to construct an elaborate explanation for all of this—parallel time-stream, Borgesian game—but the simplest rationale, beyond the mere pleasures of pastiche, would be that inventing a composer allowed Zbigniew Preisner to imitate older musical styles which were still in keeping with his own compositions. The Dekalog theme may have originated elsewhere but it doesn’t sound at odds with the beautiful bolero that Preisner composed for Red. Kieslowski and screenwriter Krzysztof Piesiewicz (who co-wrote all of these films) evidently loved constructing patterns and finding connections between their characters; Dekalog is like Joyce’s Dubliners crossed with the “Wandering Rocks” chapter of Ulysses. In these intricate scenarios Van den Budenmayer and his music become yet more tiles added to the mosaic.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The car in the snow

• Dekalog posters by Ewa Bajek-Wein