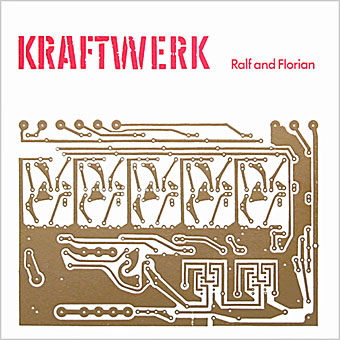

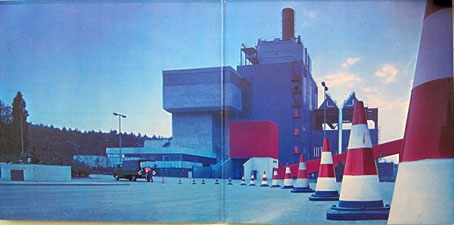

Gatefold interior for Doppelalbum (1974), a double-disc compilation album by Kraftwerk.

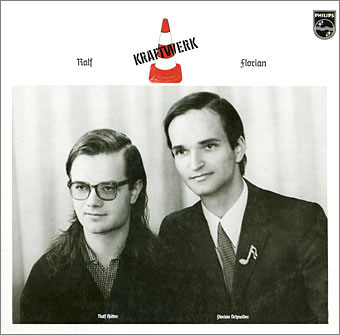

More Kraftwerkiana. “Leitkegel” is the German name for traffic cones, and it’s immediately obvious to anyone browsing Kraftwerk’s pre-Autobahn recordings that Ralf and Florian had a fixation with these objects. The closest thing I’ve found for a rationale is in Tim Barr’s history of the group, Kraftwerk: From Dusseldorf to the Future (1998), which features some musings about the influence of Joseph Beuys and the Düsseldorf arts scene of the late 60s. Prior to Kraftwerk, Florian Schneider was a member of a short-lived art collective/music outfit with the very un-Kraftwerkian name of Pissoff. Recordings exist of the group performing with Beuys. A more straightforward explanation might be to look towards Pop Art (something that Barr also suggests), with the traffic cone serving as a symbolic objet trouvé that’s also the first inkling of the future Kraftwerk obsessions with roads, trains and cycling. Whatever the impulse behind its adoption, between 1969 and 1973 the traffic cone was turning up everywhere that Ralf and Florian went.

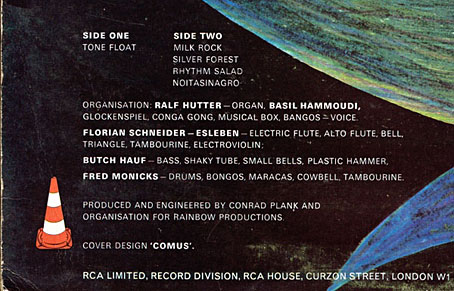

Cover design by “Comus” (Roger Wooton).

The first instance is on Tone Float (1970), the pre-Kraftwerk album by Organisation, a collection of freeform improvisations that’s very much of its time. The album wasn’t very successful, and matters weren’t helped by the poor cover artwork. That multicoloured head and Ringlet typeface are also very much of their time but if you look on the back of the sleeve you find a traffic cone beside the album credits.

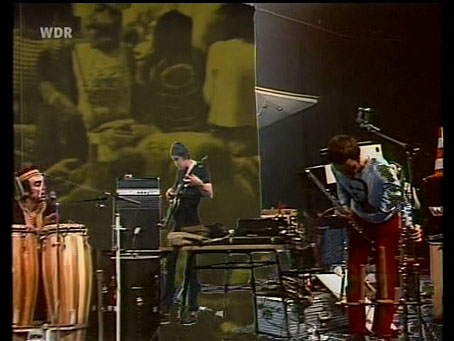

Organisation live (1970).

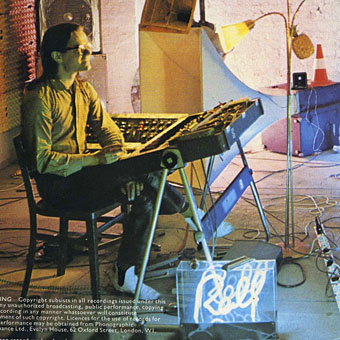

Before the group split they were recorded by German TV, a performance that gives a good idea of the Organisation sound and of how odd they all look together. Ralf Hütter isn’t visible but you do glimpse a traffic cone for a moment when Florian is moving his microphone stand. I suspect the proliferation of cones around Florian (see below) is an indicator that their adoption was his doing.