Complete Stop (2008), an oil painting by Gregory Thielker from his Under the Unminding Sky series.

• For Halloween last year I watched a very poor copy of a BBC Play For Today production, Robin Redbreast, a piece of rural horror by John Bowen which received a single screening in 1970. That poor copy—black-and-white, timecoded, multi-generation video—has been circulating for years, so it’s good to know that the BFI will be releasing Robin Redbreast on DVD in time for this year’s Halloween. This might be news enough but the following month the BFI also releases Leslie Megahey’s stunning adaptation of Schalcken the Painter in a dual DVD/Blu-ray edition. I wrote a short review of the latter film last October.

• Mixes of the week: August Sun High from The Advisory Circle, and John Wizards’ Quietus Mix “African music, R&B and chamber pop, filtered through gentle electronic arrangements that cross-pollinate with South African house, Shangaan electro and dub”.

• A trailer has surfaced for The Counselor, a film by Ridley Scott from an original screenplay by Cormac McCarthy. Trailers are too spoilerish so I’m refusing to watch it but for those interested Slate has the details.

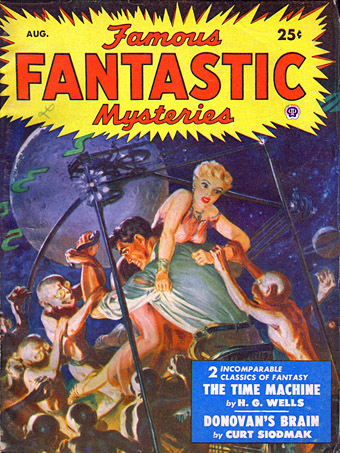

Luckhurst makes an admirable attempt to link Lovecraft’s most frustrating writing tic to this theme of the unknown when he claims that Lovecraft’s “catachresis”—deliberate muddling of language through the use of mixed metaphors and the like—is a tool he uses to bolster the atmosphere of futility in the face of “absolute otherness.” The trauma of encountering something so far outside the realms of imagination triggers a collapse of logic in the language itself.

Cate Fricke reviews The Classic Horror Stories of HP Lovecraft, a collection from Oxford University Press edited by Roger Luckhurst.

• “Contemporary audiences found it too weird, too wonky and even borderline distasteful…” Xan Brooks goes looking for the locations from Powell & Pressburger’s 1943 film, A Canterbury Tale.

• Two songs from Julia Holter’s forthcoming album, Loud City Song: World and Maxim’s I. Also unveiled this week: Evangeline, a new track by John Foxx & Jori Hulkkonen.

• Have Ghost, Will Find: Colin Fleming on William Hope Hodgson’s Carnacki, The Ghost Finder.

• At PingMag: Urban Calligraphy: Turning the Streets into Big, Loud Canvases.

• Sex, Spirit, and Porn: Conner Habib talks to Erik Davis.

• Serendip-o-matic: Let Your Sources Surprise You

• The Pronunciation of European Typefaces

• Twilight (2004) by Robin Guthrie & Harold Budd | Luminous (2009) by John Foxx & Robin Guthrie | Cling (2011) by Robin The Fog