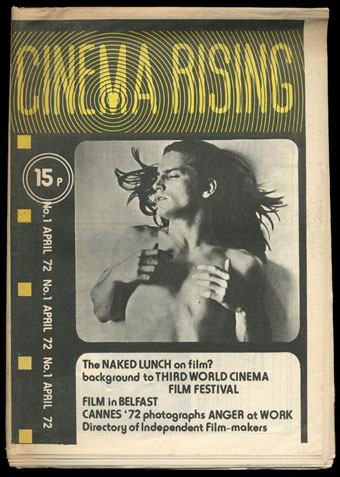

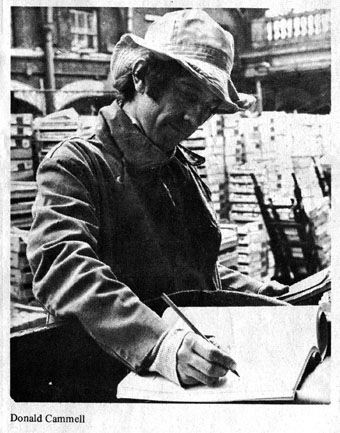

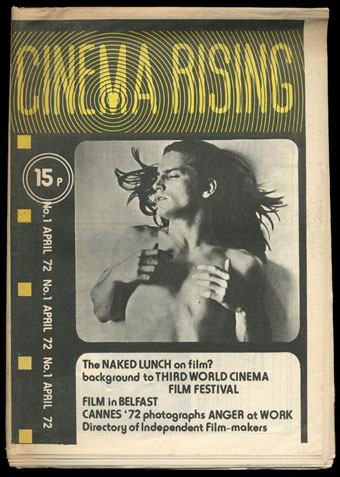

Another resurrected article. Cinema Rising was a short-lived newsprint film magazine that ran for three issues in the UK in 1972. I have a few pages from the rare first issue that was part of a batch of old underground newspapers I was given a few years ago. (The Frendz Hawkwind strip is from the same haul.) Cinema Rising was edited by Simon Hartog and Tony Rayns, the latter being a long-time Kenneth Anger aficionado which would explain both the magazine title and the presence of a photo feature about Anger’s Lucifer Rising. The bulk of this post is a short interview with Donald Cammell that’s of interest for his comments about the gender roles in Performance and his opinion of Jorge Luis Borges whose recurrence as both signifying text and presiding magus in Performance is never really explained.

Cammell’s next film after Performance would have been Ishtar (no relation to the notorious Warren Beatty flop), the themes of which Cammell discusses at the end of the piece. The Cammell biography describes a script concerning a film star and Hollywood producer who want to make a film in Morocco. While there they get involved with a woman who embodies various mystical/mythological feminine attributes; there’s also a sub-plot about the pair kidnapping an American judge. Mick Jagger was down for the role of the film star while William Burroughs was slated to play the judge. Given how wayward Cammell’s later films became it’s difficult to say whether this would have been good or not. Performance could very easily have been terrible but that film also had Nicolas Roeg on board.

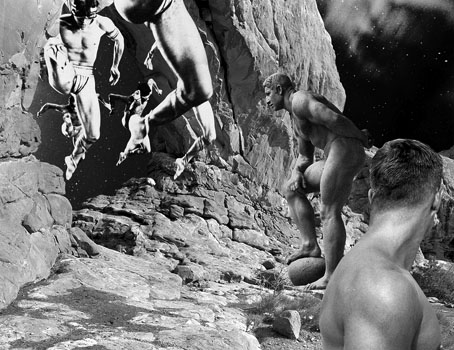

After the Cammell piece there are photos from Cinema Rising‘s Kenneth Anger feature which show the director at work on the new version of Lucifer Rising. I’ve not seen any of these stills or the two black actors before—what happened to their parts? Note that some of the captions are misspelled: the photos should be credited to Diarmid Cammell—Donald’s brother—while the Adept (not “Lucifer”) is Haydn Couts. •

DONALD CAMMELL: PERFORMANCE TO ISHTAR, Cinema Rising, no. 1, April 1972

Donald Cammell’s first movie was Performance, made in collaboration with Nicolas Roeg; the most unexpected British movie of recent years, and one of the very few products of the British industry capable of holding its own in an international context. Cammell’s new script is Ishtar, originally written with Mick Jagger in mind for the lead again, but possibly to be made without him; Cammell is currently in America to raise the backing for the film.

In the following extracts from a conversation with John du Cane (recorded last year), Cammell speaks of his background and interests…matters that inform his new script at least as much Performance.

Collaboration

“In the recent past, reverence for the director of a film as sole creator has been vastly exaggerated, through critical efforts. I’m thinking particularly of the Cahiers du Cinema ‘author’ concept—I’ve been living in Paris, and have been quite aware of it for a long time. The kind of theory of creativity that’s arisen there (and in related worlds in New York) is, succinctly, crap. It’s a way of trying to demonstrate the view that cinema is an artform, and that therefore there must be a single creative mind controlling the artefact, through to its ultimate form. It’s a way of justifying movie-making, socially and culturally.

“But leaving aside the reasons for the concept, I think it’s contradicted by the facts. I think that many of the greatest artefacts things that have moved people most throughout history—have been collectively produced. You don’t even have to look for examples: the whole of Egyptian culture, arcane cultures generally. Today in tribal cultures, the vast majority of the products are collectively produced. The hangup is the concept of one ego necessarily controlling the production in order for that ego to be expressed; the notion that the expression of an ego is the final goal of any artwork, that this is what it’s for. I think that an artwork expresses itself, that the creators involved will all see in it their own egos, each one individually satisfied when looking at the final work. My analogy is with contemporary music, where people go into it collectively, and their egos are satisfied collectively and individually. Look at Mick and Keith and their confreres: they see in their work as The Rolling Stones what they each wanted to say. Working in the film medium is ideally suited to interaction of different heads; it’s the ideal medium for all the good functions of collective work.”

Continue reading “Donald Cammell and Kenneth Anger, 1972”