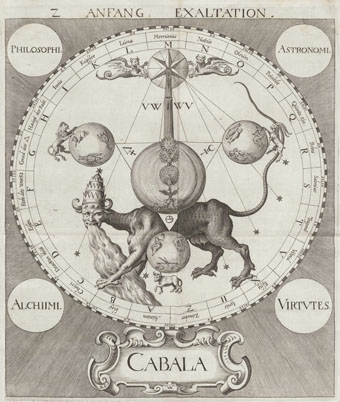

An engraving by Rafael Custos from Cabala, Spiegel der Kunst und Natur, In Alchymia (1615) by “Father C.R.C.”.

• “Writing is very subconscious and the last thing I want to do is think about it.” Cormac McCarthy responded to a handful of questions from a couple of lucky high-school students. Lithub’s list of McCarthy’s rare public manifestations missed this chatty encounter with the Coen Brothers from 2007.

• Strange Flowers celebrates Rosa Bonheur, “the most famous and successful woman artist of the 19th century, dressing in men’s clothing, smoking cigars, riding astride and living openly with female partners.”

• A Secret Between Gentlemen by Peter Jordaan “details a British Government coverup of a gay scandal involving great names. Hidden for 120 years, it is a history that has never been told, and until recently could not be told.”

[Mark E. Smith] liked HP Lovecraft, whose monster of The Call of Cthulhu and The Dunwich Horror appears in the song N.W.R.A., “Body a tentacle mess”. He quite liked MR James’ Ghost Stories. He liked the more recent, seemingly disgraced, and by then unfashionable, occult fiction of Colin Wilson: The Black Room and Ritual in the Dark. But He LOVED the writing of early twentieth century Arthur Machen. “Machen’s fucking brilliant.” In his autobiography Renegade he comments, “He lives in this alternative world: the real occult’s not in Egypt, but in the pubs of the East End and the stinking boats of the Thames—on your doorstep, basically.”

Woebot goes deep into the grotesque and esoteric worlds of Mark E. Smith and The Fall

• “It sometimes seems as though inn signs are the symbols and the focus of some great alchemical experiment in the landscape of England.” Mark Valentine on inn signs and some of the theories about their origins.

• “…we’re going back into this shipwreck and, you know, pulling out the gold pieces”. Dennis Bovell on reworking the Pop Group’s incendiary debut album as Y in Dub.

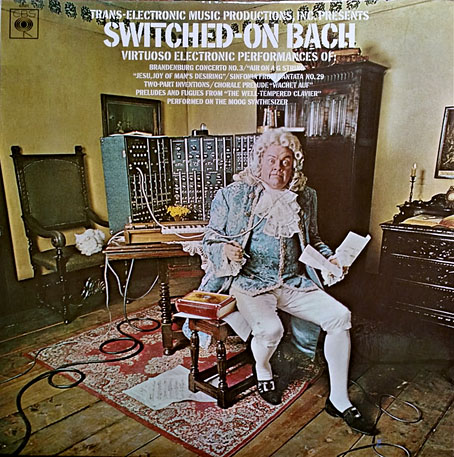

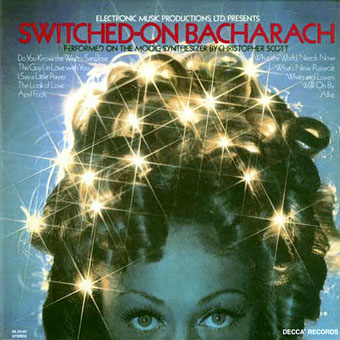

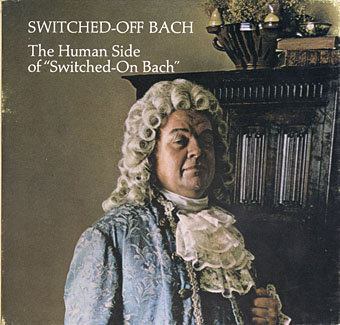

• Mixes of the week: A Wendy Carlos mix by Erik DeLuca for The Wire, and a psychedelic/post-punk mix by Robert Hampson for NTS.

• Landscapes is an exhibition of torn-paper collages by Jordan Belson at Matthew Marks Gallery, New York.

• “A force entirely of itself”: Robert Fripp on the difficult legacy of King Crimson.

• White Landscape I (1971) by Douglas Leedy | John Cage: In A Landscape (1994) performed by Stephen Drury | Primordial Landscape (2013) by Patrick Cowley