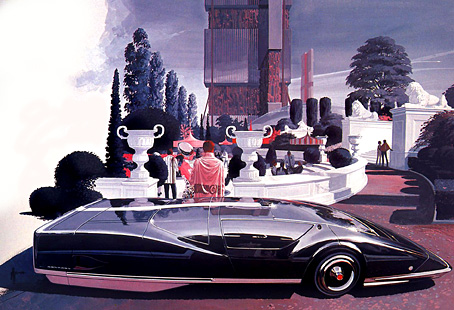

The Sentinel 280, a car design by Syd Mead from 1964.

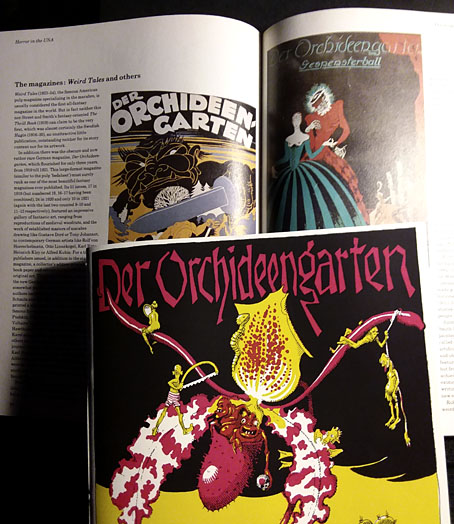

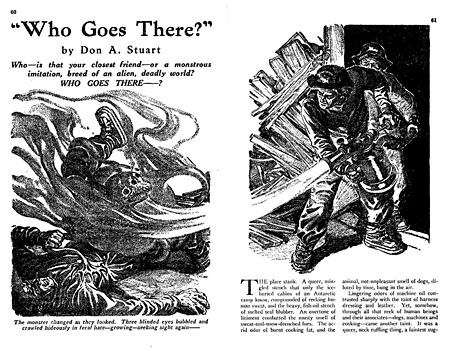

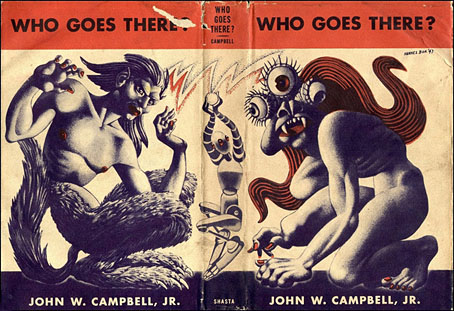

• “Boris Dolgov did not exist. The man who bore that name may have existed, but there never was a man in the United States with that name until 1956, too late for Weird Tales.” Teller of Weird Tales on the mysterious identity of a magazine artist.

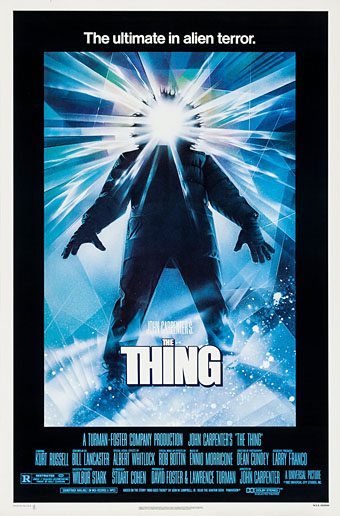

• Saying goodbye to 2019 also meant saying farewell to Vaughan Oliver, Neil Innes and Syd Mead. Related: Vaughan Oliver at Discogs; I’m The Urban Spaceman; a look back at Syd Mead’s vehicle designs.

• Lanre Bakare on how ambient music became cool. (Again. This begs the question of when it became uncool, especially when a ten-year-old Brian Eno piece about “the death of uncool” is being quoted.)

Westerners interpreted the peyote experience very differently from the practitioners of the peyote religion, where the focus was “ritual, song and prayer, and to dissect one’s private sensations was to miss the point”. Writers such as Havelock Ellis, who published an essay on his peyote experiences in the Lancet in 1897 (it’s likely that he also administered the substance to his friends W.B. Yeats and Arthur Symons), instead tended to focus on its visual effects. Ellis described “the brilliance, delicacy and variety of the colours” and “their lovely and various textures”. Peyote reached Europe in tandem with the X-ray, cinema and electric lights, Jay notes, and “nothing delighted the eye of the mescal eater so much as the new electrical sublime”.

Emily Witt reviewing Mescaline: A Global History of the First Psychedelic by Mike Jay

• Peter Bradshaw takes on the thankless task of ranking Federico Fellini’s feature films.

• Geoff Manaugh on when Russia and America coöperated to avert a Y2K apocalypse.

• “Music is an ideal medium for interstellar communication,” says Daniel Oberhaus.

• Keith Allison on Karel Zeman, a creator of remarkable cinematic fantasies.

• Japanese Designer New Year’s Cards of 2020.

• At Dennis Cooper’s: Vera Chytilová Day.

• Sentinel (1992) by Mike Oldfield | Sentinels (2001) by Cyclobe | Sentinel (2004) by Transglobal Underground