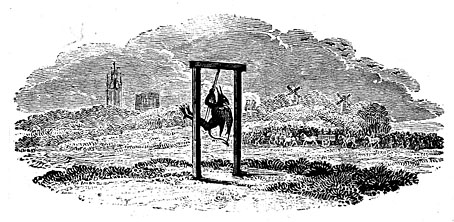

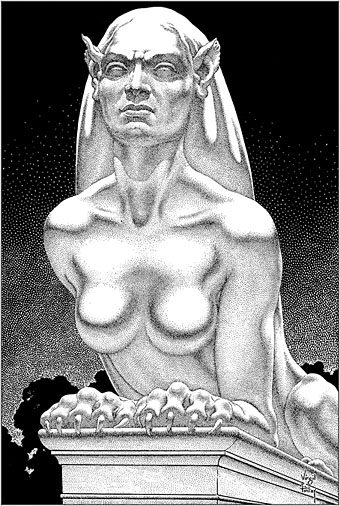

The Time Machine by HG Wells; Famous Fantastic Mysteries, August 1950.

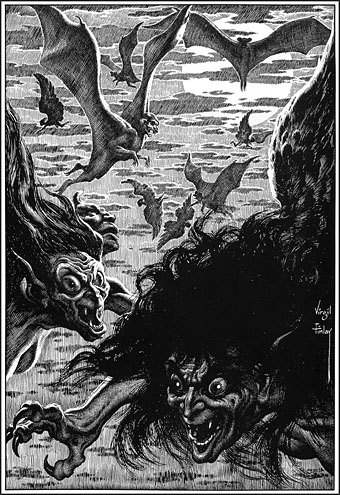

This one will be popular, I’m sure. One of the recent uploads at the Internet Archive is a massive collection of Virgil Finlay’s interior illustrations from the magazines that published most of his work—Weird Tales, Famous Fantastic Mysteries, Amazing Stories, etc, etc—together with the astrological illustrations he created later in his career, plus other material, including a few pieces that never appeared in print. Pencil drawings, lithographs and hundreds of meticulous renderings in ink on paper or scratchboard; 1888 illustrations in all. Whoever put the haul together has been much more thorough than I’d have expected. Rather than a stash of random drawings you get 10 separate folders (best appreciated in the cbz format; see the note below) with each illustration tagged with the name of the story it was illustrating, and the date of publication. The contents are a mix of reproductions from later reprints, together with cropped pages from magazine scans. Taken together, this must comprise almost all of Finlay’s published work excluding his magazine covers and other paintings.

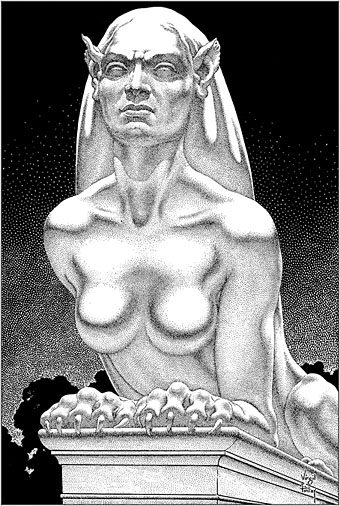

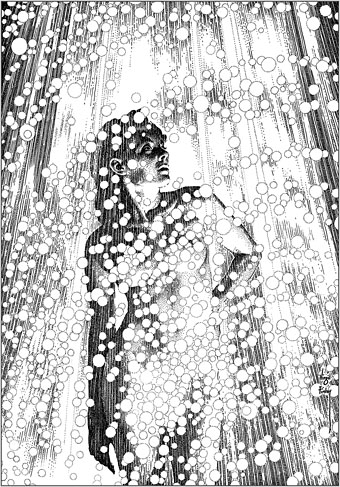

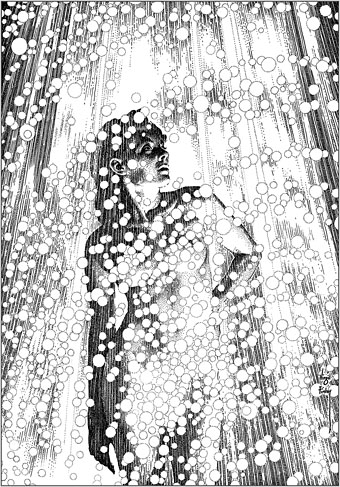

Earth’s Last Citadel by Henry Kuttner and CL Moore; Fantastic Novels Magazine, July 1950.

Virgil Finlay (1914–1971) can be a frustrating artist for anyone who admires his work. He was massively prolific, and maintained a high level of quality for almost 40 years; but his interior illustrations were often printed on pulp stock, the kind of paper that offers the worst kind of print reproduction, and which darkens and eventually crumbles into dust unless it’s carefully stored. Descriptions of his illustrations often note that his drawing style evolved to compensate for the deficiencies of the printing but much of his artwork was very finely rendered, and I’m not sure his minute stipple effects would have printed any better (or worse) than the traditional cross-hatching which he used from time to time. His drawings have at least been well-served by reprint collections, where the white art paper makes his striking compositions leap off the page. Inevitably, the best of these—Gerry de la Ree’s seven-volume collection from the 1970s, and a four-volume set from the 1990s—are all out of print. The sheer quantity of illustrations also presents a problem for any reprint collection: what to include…or leave out? All of which is a roundabout way of saying that this accumulation of his interior art may be unauthorised, and even frowned upon by some, but it benefits Finlay by keeping his work in circulation and showing the full range of his career.

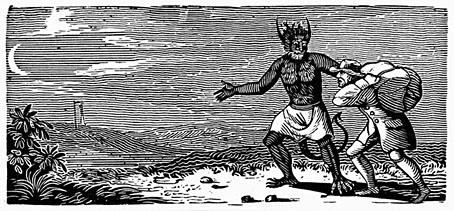

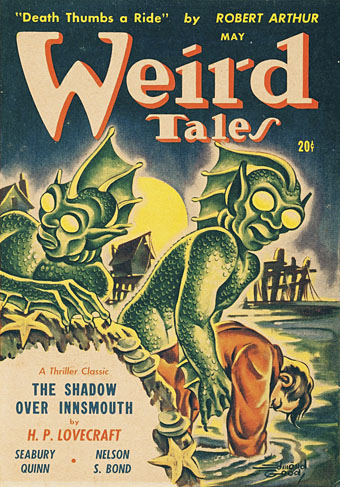

The Faceless God by Robert Bloch; Weird Tales, May 1936.

With 1888 illustrations to choose from, picking out a representative selection is a hopeless task, so what you see here are a few favourites. I said that Finlay maintained a high level of quality but there are unsuccessful Finlays, especially in the early years when his style was still evolving. (It should be noted that he was in his early twenties when he was creating pieces such as these. His errors are a lot less grievous than mine were at the same age.) One of the hallmarks of the Finlay style is a frequent use of photo-reference, especially for faces, and it’s the disjunction between faces and bodies which occasionally jars. Disparities between the size or angle of a head and a body are common in photo-collage but you don’t expect to see them in a drawing. Occasionally the disparities worked for him, as in his illustration for The Faceless God by Robert Bloch, a drawing that so impressed HP Lovecraft that he responded with a short poem praising both picture and artist. The reference images used for his later work are much more seamlessly integrated, and in the 1940s and 50s he seemed to be using posed models as frequently as the illustrators for the big American magazines.

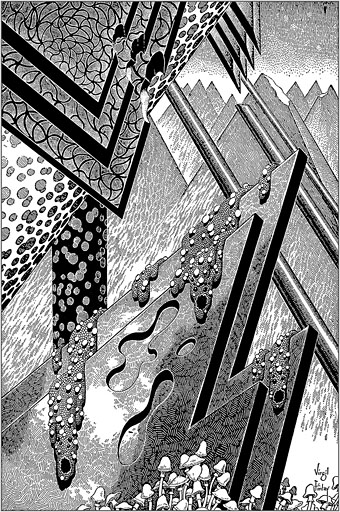

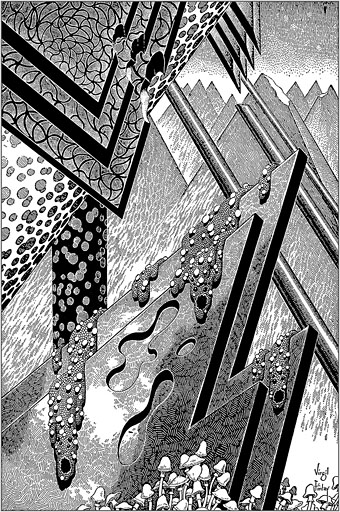

The Man Who Mastered Time by Ray Cummings; Fantastic Novels Magazine, March 1950. Remove the fungi from this illustration and you’d have an almost abstract image.

Regarding cbz or cbr files: these are simply folders filled with jpegs or pngs which have been zipped then given a new suffix. They can be browsed using a suitable comics-reader application; I use Simple Comic for the iMac and ComiCat for the tablet. The files can also be opened with any unzipping software to give you access to the images inside. I find these files so much easier to use than pdfs, especially for image-heavy publications, that I’ve taken to exporting pdf pages as jpegs then zipping a folder of the images into a cbr. One of the advantages of the cbr format is that the readers allow you to extract an image without unzipping the whole file. The only drawback with the Finlay files is that ComiCat doesn’t let you see the file name the way that Simple Comic does.

Full Moon by Talbot Mundy; Famous Fantastic Mysteries, February 1953.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The illustrators archive

• The Lovecraft archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Virgil Finlay’s Tarzan

• Virgil Finlay’s Salomé

• The monstrous tome