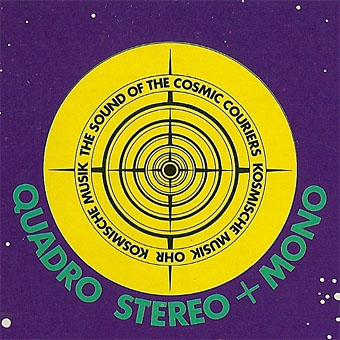

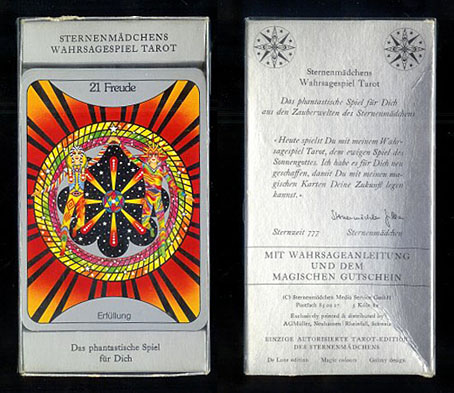

Revelation of the weekend has been the discovery that there are two sets of (for want of a better term) Krautrock Tarot cards. The first, Walter Wegmüller’s Zigeuner Tarot, is familiar for being included in the Tarot concept album released on the Kosmischen Kuriere label in 1973. The album was credited to Wegmüller but he only advised on the symbolism and acts as MC/narrator. Wegmüller’s cards are detailed and somewhat original, but their drawing is from the enthusiasm-over-technique school which goes against the grain of the rest of the album design and the accomplishment of the musicians.

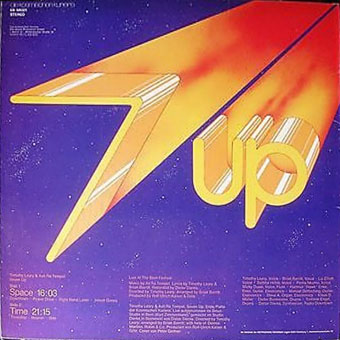

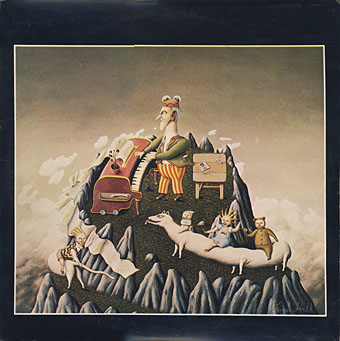

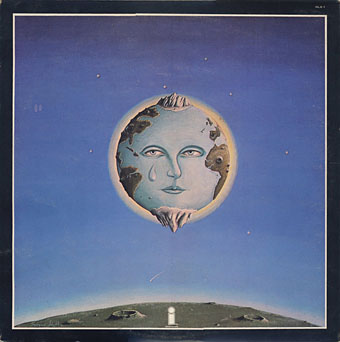

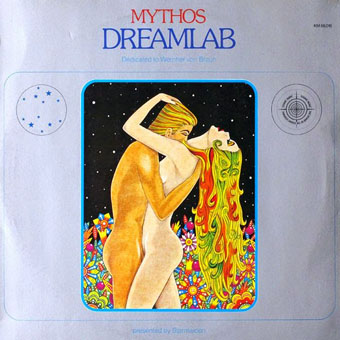

Dreamlab (1975) by Mythos. Design by Peter Geitner.

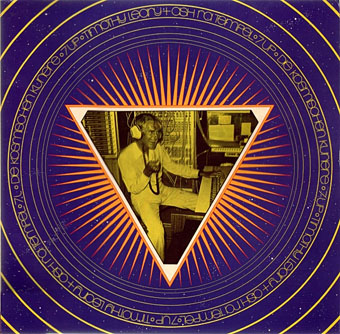

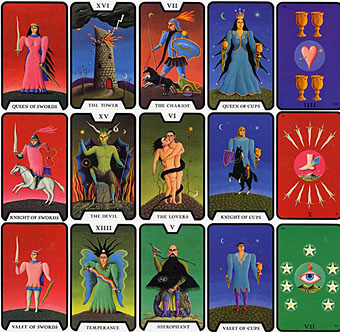

As noted a few days ago, the designer of the Tarot album was Peter Geitner working under the direction of a pair of very hands-on label bosses, Rolf-Ulrich Kaiser and Gille Lettmann. The story of Kaiser’s rise and fall has been recounted in some detail over the years (see here and here). Given the colourful saga, and the cast of notable musicians, writers and artists, I’m surprised to have seen no mention of the second Tarot set that Peter Geitner designed and illustrated in 1975 while the Kosmische Musik empire was imploding. One illustration (The Lovers) was even used as cover art for the Dreamlab album by Mythos.

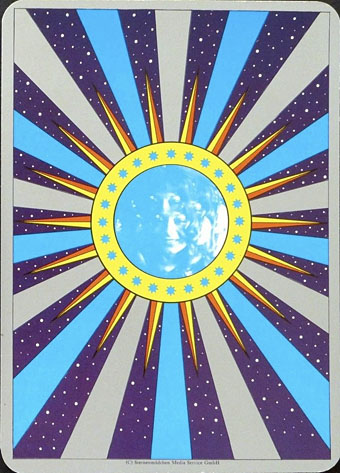

Card back for the Sternenmädchen’s Wahrsagespiel.

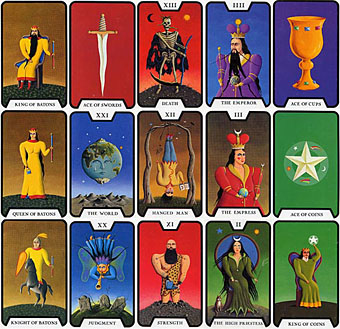

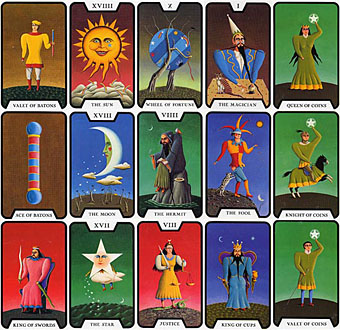

Sternenmädchen’s Wahrsagespiel (Star Girl’s Fortune Telling Game) is a specialised set of the Major Arcana presented as a spin-off from Gille Lettmann’s Sternenmädchen persona as featured on the Gilles Zeitschiff album; the back of the 22 cards features the photo of Gille from the album cover. I’ve said that Geitner illustrated the cards but some of the drawings may have originated as sketches by Gille Lettmann; information is scant but I’ve seen mention of her having been a textile or fashion designer. What’s most striking to me about these designs is how psychedelic they all are, more so than any of the Kosmische Musik album covers even though they maintain the cosmic themes of the record label. Many of those involved with the Kosmische empire were taking LSD at the time so this isn’t very surprising but psychedelia of this intensity was an outmoded thing by the mid-70s. Also of interest is the renaming of the cards which push the attributions away from medieval tradition and into the cosmos. I’ve not been able to find examples of all 22 designs but a list of the cards follows, together with examples of variable quality. The set was printed by AGM Müller but has never been reissued so it now commands high prices. (Many thanks to Jeff for drawing my attention to these!)