The Crystal Ball (c. 1900) by Robert Anning Bell.

Crystal balls in art, film and the pulp magazines.

The Crystal Ball (1902) by John William Waterhouse.

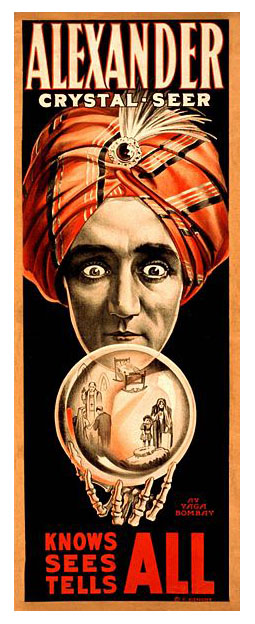

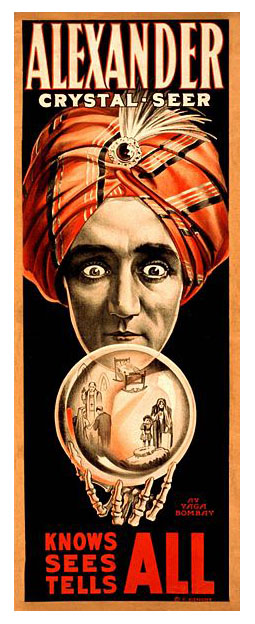

Alexander, Crystal Seer (1910).

A journal by artist and designer John Coulthart.

The Crystal Ball (c. 1900) by Robert Anning Bell.

Crystal balls in art, film and the pulp magazines.

The Crystal Ball (1902) by John William Waterhouse.

Alexander, Crystal Seer (1910).

Untitled etching by Etsuko Fukaya, 2005.

• “By the time Scorsese met Powell, in 1975, the British director had fallen on hard times and was largely ignored by the UK film establishment.” A London office used by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger is given the Blue Plaque treatment.

• Ambient reminiscences at The Quietus: Wyndham Wallace on the genesis of Free-D (Original Soundtrack) by Ecstasy Of St Theresa, and Ned Raggett on Aphex Twin’s Selected Ambient Works II.

• “Even Queen Victoria was prescribed tincture of cannabis,” writes Richard J. Miller in Drugged: the Science and Culture Behind Psychotropic Drugs. Steven Poole reviewed the book.

I don’t relate to standard psychologizing in novels. I don’t really believe that the backstory is the story you need. And I don’t believe it’s more like life to get it—the buildup of “character” through psychological and family history, the whole idea of “knowing what the character wants.” People in real life so often do not know what they want. People trick themselves, lie to themselves, fool themselves. It’s called survival, and self-mythology.

Rachel Kushner talking to Jonathan Lee

• Sound Houses by Walls is a posthumous collaboration based on a collection of “weird sonic doodles” by electronic composer Daphne Oram. FACT has a preview.

• The skeletal trees of Borth forest, last alive 4,500 years ago, were uncovered in Cardigan Bay after the recent storms stripped the sand from the beach.

• Stephen O’Malley talks to Jamie Ludwig about Terrestrials, the new album by Sunn O))) and Ulver. There’s another interview here.

• At BibliOdyssey: Takushoku Graphic Arts—graphic design posters by contemporary Japanese artists.

• The Unbearable Heaviness of Being: Dave Segal on the rumbling splendour of Earth 2.

• So Much Pileup: “Graphic design artifacts and inspiration from the 1960s – 1980s.”

• Lots of illustrations by Virgil Finlay being posted at The Golden Age just now.

• Mix of the week: Episode #114 by Lustmord at Electric Deluxe.

• Lucinda Grange’s daredevil photography. There’s more here.

• Experimental music on Children’s TV

• Kazumasa Nagai at Pinterest.

• Teeth Of Lions Rule The Divine (1993) by Earth | He Who Accepts All That Is Offered (Feel Bad Hit Of The Winter) (2002) by Teeth Of Lions Rule The Divine | Big Church (megszentségteleníthetetlenségeskedéseitekért) (2009) by Sunn O)))

Illustration by Lawrence for The Undying Monster (1946) by Jessie Kerruish.

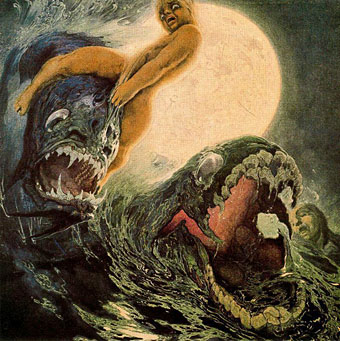

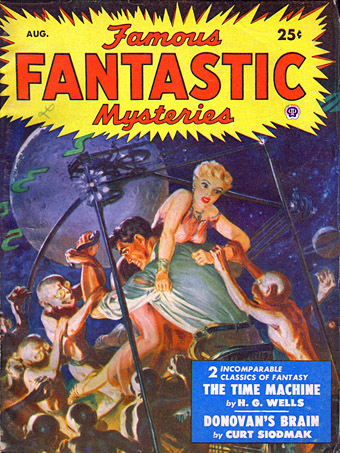

Another of those collisions between fine art and pulp fiction that I like to note now and then. The drawing above by Lawrence Sterne Stevens (from this page) I immediately recognised as borrowing its fish from the painting below by Néstor Martín-Fernández de la Torre (1887–1938), or Néstor as he’s usually known. Stevens was also usually credited by the single name Lawrence, and this is one of his many first-rate contributions to Famous Fantastic Mysteries. I’ve already noted a similar borrowing by his contemporary, Virgil Finlay, so this example isn’t too surprising. It’s unlikely that many of the readers eagerly devouring Jessie Kerruish’s tale would have been familiar with Néstor’s paintings. On the same Lawrence page there’s his illustration for Arthur Machen’s The Novel of the Black Seal which ran in the same issue.

Poema del Mar: Noche (1913–1924).

Néstor is distinguished by a predilection for aquarian scenes and writhing figures, all of which are presented in a very distinctive and recognisable style. He also happens to be one of the few major artists to come from the Canary Islands which no doubt explains his interest in the sea. The Poema del Mar series, and other works such as this satyr head, often find him numbered among the Spanish Symbolists although he’s rather late for that movement, and this assumes that every artist has to be placed in one box or another whether they belong there or not. These giant fish could just as well make him another precursor of the Surrealists, and they do occasionally receive a mention for their similarity to (and possible influence upon) Dalí’s enormous Tuna Fishing (Homage to Meissonier) (1966–67). There’s more of Néstor’s work over at Bajo el Signo de Libra (Spanish language).

Poema del Mar: Tarde (1913–1924).

Poema del Mar: Reposo (1913–1924).

Weird Tales, October 1933. Cover art by Margaret Brundage.

• Michael Moorcock’s novels are being republished this year by Gollancz in a range of print and digital editions. Publishing Perspectives asks Is Now a Perfect Time for a Michael Moorcock Revival? • Related: Dangerous Minds posted The Chronicle of the Black Sword: A Sword & Sorcery Concert from Hawkwind and Michael Moorcock. My sleeve for that album was the last I did for the band. • Obliquely related: Kensington Roof Gardens appear as a location in several Moorcock novels, and also provided a venue for the author’s 50th birthday party. If you have a spare £200m you may be interested in buying them once Richard Branson’s lease expires.

• One of my favourite things in Mojo magazine was a list by Jon Savage of 100 great psychedelic singles (50 from the UK, 50 from the US). This week he presented a list of the 20 best glam-rock songs of all time. For the record, Blockbuster by The Sweet was the first single I bought so I’ve always favoured that song over Ballroom Blitz.

• The Alluring Art of Margaret Brundage is a forthcoming book by J. David Spurlock about the Weird Tales cover artist. Steven Heller looks at her life (I’d no idea she knew Djuna Barnes) while io9 has some of her paintings. Related: Illustrations for Weird Tales by Virgil Finlay.

The masterpiece of Mann’s Hollywood period is, of course, Paracelsus (1937), with Charles Laughton. Laughton’s great bulk swims into pools of scalding light out of greater or lesser shoals of darkness like a vast monster of the deep, a great black whale. The movie haunts you like a bad dream. Mann did not try to give you a sense of the past; instead, Paracelsus looks as if it had been made in the Middle Ages – the gargoyle faces, bodies warped with ague, gaunt with famine, a claustrophobic sense of a limited world, of chronic, cramped unfreedom.

The Merchant of Shadows (1989) by Angela Carter. There’s more of her writing in the LRB Archive.

• Television essayist Jonathan Meades was back on our screens this week. The MeadesShrine at YouTube gathers some of his earlier disquisitions on culture, place, buildings and related esoterica.

• Sometimes snark is the only worthwhile response: An A-Z Guide to Music Journalist Bullshit.

• London venue the Horse Hospital celebrates 20 years of unusual events.

• The Politics of Dread: An Interview with China Miéville.

• How Giallo Can You Go? Antoni Maiovvi Interviewed.

• A guide to Terry Riley’s music.

• Three more for the glam list: Coz I Love You (1971) by Slade | Get It On (1971) by T. Rex | Starman (40th Anniversary Mix) (1972) by David Bowie

The Time Machine (1960).

The turning over of the calendar from one year to the next makes this day the ideal moment to write something about HG Wells’ celebrated story. Having re-read The Magic Shop before Christmas I decided to refresh my reading habit—lapsed these past months due to pressure of work—by revisiting more of Wells’ short stories, many of which I haven’t looked at for years.

As I said in that earlier post, it was The Time Machine that led me to Wells’ written work after being excited at an early age by George Pal’s 1960 film adaptation. Reading the story again I’m still astonished by how advanced it is compared to everything else being published in 1895. Michael Moorcock’s excellent introductory essay, The Time of ‘The Time Machine’ (1993), notes that time travel per se wasn’t a new idea for Victorian readers, there were many novels and stories using the theme, most of them merely displacing a character from one age to the next in a very simple manner. Wells’ innovation was the idea of a machine which would give the user mastery of Time itself. Moorcock also notes that Wells considered this to be his one great idea which he always felt he never exploited as fully as he wished. The need to make a living forced him to set down the story in some haste when it was accepted for serialisation in WE Henley’s New Review. (Moorcock’s introduction can be found in a recent collection London Peculiar and Other Nonfiction).

The other notable feature this time round—and this means more to me than it would to many other readers—was being struck by the way Wells’ story prefigures so much of the fiction William Hope Hodgson would be writing a decade or so later. It’s a commonplace among Hodgson scholars that The Night Land (1912) owes something to the scenes when the Time Traveller journeys beyond the age of the Eloi and Morlocks to a period when the Earth is dead and the Sun has swollen to a baleful giant. Some of the more cosmic moments of The House on the Borderland (1908) can also be traced back to these scenes. I’d argue that the Time Traveller’s earlier battles with the Morlocks prefigure and possibly influence similar battles in The Night Land, and the attacks of the Swine-Things in Borderland. There’s even a moment near the end of Wells’ story when the Time Traveller is menaced by giant crustaceans like those which infest Hodgson’s Sargasso Sea. This may not be a fresh observation but it’s not one I’ve seen elaborated before.

Regular readers will know it’s a habit here to seek out illustrations of favourite stories. In the case of The Time Machine there are hundreds to choose from so the following selection barely scratches the surface. Something I’d not noticed before when looking at comic strip adaptations is that none of the works derived from Wells’ story (George Pal’s film included) seem able to countenance the Time Traveller’s abandoning of Weena to the Morlocks when the pair become trapped outdoors at night; all show the Time Traveller doing his best to rescue her. William Hope Hodgson’s fiction is filled with rescues, sieges and the defence of the weak against marauding and inhuman forces; The Night Land concerns an epic and apparently suicidal rescue mission across the most inhospitable terrain imaginable. It may be stretching a point but it’s possible to see much of Hodgson’s fiction as being a riposte to this incident in Wells’ story.

Illustration by George Saunders (August, 1950).

Recurrent points of interest in illustrations of Wells’ story are i) How is the Time Machine itself depicted? (The author’s descriptions are evasive), and ii) How are the Morlocks depicted? Wells describes them thus:

‘I turned with my heart in my mouth, and saw a queer little ape-like figure, its head held down in a peculiar manner, running across the sunlit space behind me. It blundered against a block of granite, staggered aside, and in a moment was hidden in a black shadow beneath another pile of ruined masonry.

‘My impression of it is, of course, imperfect; but I know it was a dull white, and had strange large greyish-red eyes; also that there was flaxen hair on its head and down its back. But, as I say, it went too fast for me to see distinctly. I cannot even say whether it ran on all-fours, or only with its forearms held very low.

George Saunders’ small Gollum-like creatures are closer to Wells’ conception than many later depictions. Saunders’ Weena, on the other hand, is far too tall for the equally diminutive Eloi.

Virgil Finlay (1950).

This is still my favourite Time Machine illustration but then Finlay has a tendency to beat everyone when it comes to these assignments. His illustrations appeared inside the August, 1950 issue of Famous Fantastic Mysteries. Wells’ sphinx has wings which I imagine Finlay might have included if he wasn’t restricted by the space allowed for his illustration. He also provided the illustration of a Morlock below.