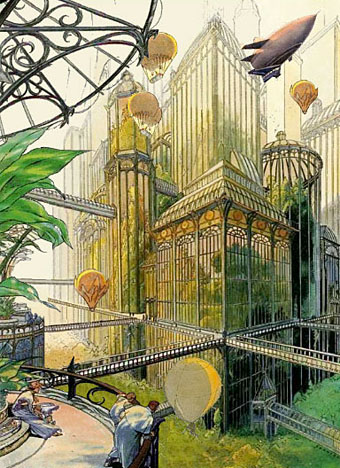

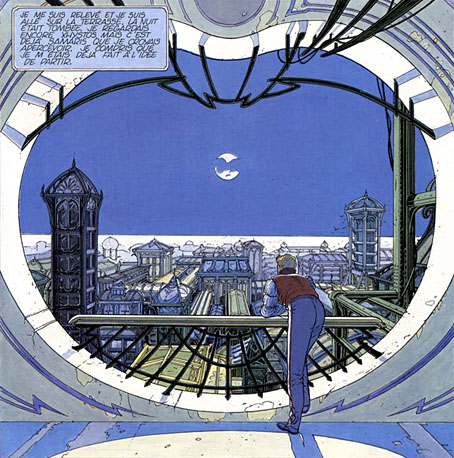

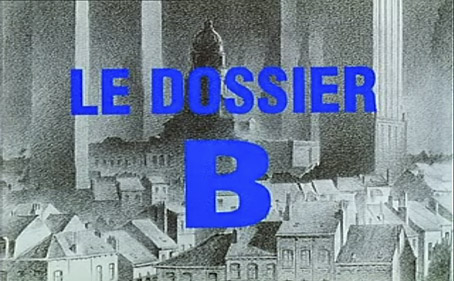

Almost ten years have elapsed since I devoted a week of blog posts to one of my favourite fantastic creations, the Obscure World/Obscure Cities of Belgian artist-and-writer team François Schuiten and Benoît Peeters. Schuiten and Peeters’ mythos is a multi-media project with a series of bande desinée albums as its core, a cycle of stories which introduce the reader to some of the cities in the Obscure World (a “counter-Earth” on the opposite side of our Sun), and which are connected by recurrent characters and motifs. Since the completion of the core series, Schuiten, with occasional help from Peeters, has expanded the mythos to encompass other books that flesh out some of the world’s invented history and its connections to our own world, together with other manifestations such as art exhibitions and music releases. Le Dossier B (1995) is a peripheral Obscure World production, a 54-minute TV documentary which entangles the genuine history of 20th-century Brussels with an invented secret society who believe in the existence of a twin city, Bruzel, that intersects with the Belgian capital.

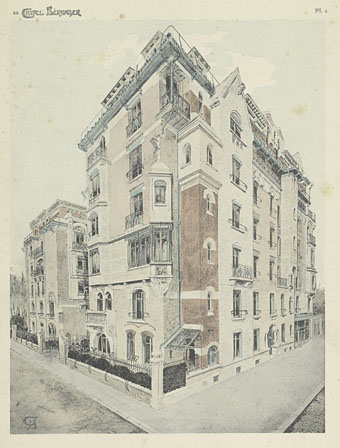

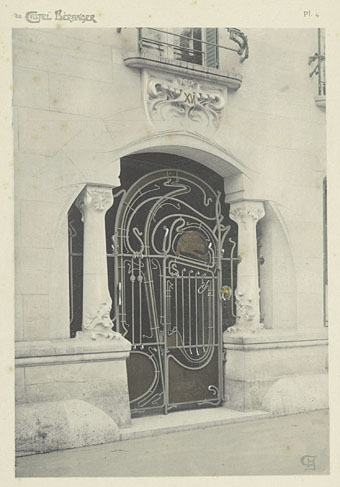

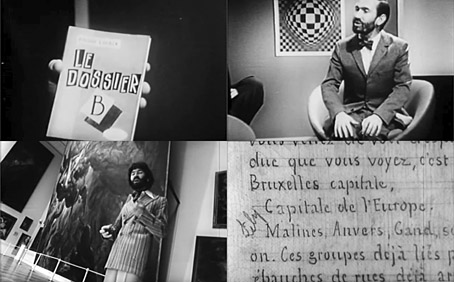

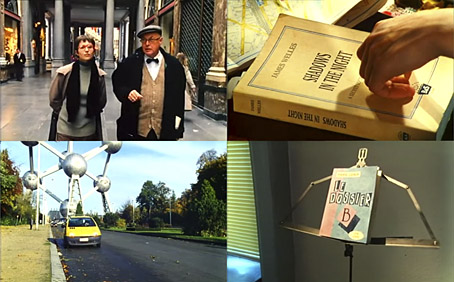

Le Dossier B was directed by Wilbur Leguebe from a script by Leguebe with Schuiten and Peeters. Valérie Lemaître plays the on-camera investigator, “Claire Devillers”, while artist and writer appear in roles that match their personalities. Schuiten is seen in silent footage as “Robert de la Barque”, an artist whose obsession with Brussels’ vast Palace of Justice provides clues to the Bruzel mystery via the eccentricities of its architect, Joseph Poelaert. Peeters appears later in the investigation as “Pierre Lidiaux” the author in 1960 of Le Dossier B (a book which has since vanished), his own study of the connections between Brussels and Bruzel. We first see Lidiaux being interviwed on a TV arts show, then later as the presenter of his own eccentric and unfinished film about Antoine Wiertz, the real-life Belgian painter of vast canvasses on morbid subjects whose museum Lidiaux explores. Aside from the well-realised historical fakery, one of the pleasures of Leguebe’s witty and imaginative documentary is the spotlight it throws on the history and culture of Brussels and Belgium. I hadn’t realised, for example, that the Wiertz Museum is so close to the European Parliament building which was still under construction when the film was being made. Elsewhere there are references to Magritte, Delvaux and Art Nouveau architect Victor Horta, and we catch a glimpse of work by another great Belgian painter, Jean Delville.

The last third of the film is based around the researches of one James Welles (Adrian Brine), a British historian whose book-length study, Shadows in the Night: A Secret Society in Belgium, explores the connections of yet more historical figures with the Bruzel mystery, including the aforementioned Horta and chemist Ernest Solvay. The historian’s surname may be taken as a deliberate choice: Orson Welles was the director of another documentary mixing fact and fiction, F for Fake, while Welles’ appearance as Falstaff in Chimes at Midnight provided Schuiten with the model for the central character in La Tour, one of the albums in Schuiten and Peeters’ Obscure Cities series.

Some of this territory is explored in another of the Obscure Cities albums, Brüsel, especially the building of the Palace of Justice and the concept of “Brusselisation”, a pejorative French term for the rapid demolition of historical quarters of a city to make way for new construction. Where Brüsel has the freedom of the comics medium to refashion the capital in a fantastic manner, Le Dossier B uses the material of our world to suggest another city (possibly the one depicted in the album) whose existence we never see. Apart, that is, for the suggestion near the end of the film that the Bruzel of the secret society is the Brussels of today, a city which has overwritten the Brussels of a century ago, just as the invented encyclopedia in Borges’s Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius gradually changes the world at large to match its contents.

Le Dossier B is available on DVD but seems to be sold out for now. Alternatively, it may be watched at YouTube in an unsubtitled copy that’s been uploaded in the wrong aspect ratio. The really determined may wish to do what I did: download the video, grab some English subtitles, then watch it in VLC with the aspect ratio set to 16:10. A lot of messing around but it works.

(My thanks to Brussels resident Anne Billson for the YT link!)

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Urbatecture

• Echoes of the Cities

• Further tales from the Obscure World

• Brüsel by Schuiten & Peeters

• La route d’Armilia by Schuiten & Peeters

• La Tour by Schuiten & Peeters

• La fièvre d’Urbicande by Schuiten & Peeters

• Les Murailles de Samaris by Schuiten & Peeters

• The art of François Schuiten

• Taxandria, or Raoul Servais meets Paul Delvaux