Secret Bloom (2014) by Natalie Shau.

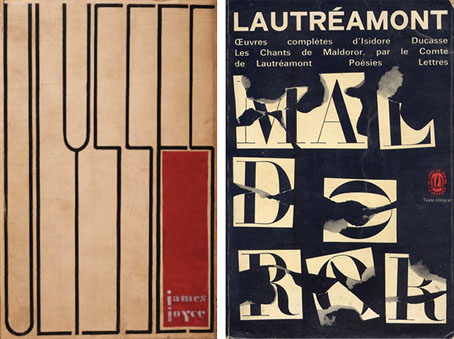

Bloomsday approachs. “Reading Ulysses changed everything I thought about language, and everything I understood about what a book could do,” says Eimear McBride whose debut novel, A Girl Is a Half-formed Thing, recently won the first Bailey’s women’s prize for fiction. McBride was interviewed by Susanna Rustin last month, shortly before the award was announced, and her novel has now become one of those minor causes célèbres for being rejected so often it was eventually published by a new imprint set up by a bookseller. “If the publishing industry doesn’t take a risk then who will?” asks Henry Layte, the bookseller in question.

Speaking of risk, David Hebblethwaite coincidentally wrote a post earlier this week asking where the formal challenge has gone in science-fiction writing. (He mentions McBride in passing.) Nina Allen followed up with a post of her own. I suspect the books are still being written but they’re no longer being accepted by editors and publishers who want even more adventure stories, “sympathetic” characters, and easy reads. Novels that only aspire to be written equivalents of action films or computer games are doomed to be less exciting than their more kinetic competitors. The struggle between the values of art and the values of entertainment is an old one but it shouldn’t be an either/or proposition. “Difficulty is subjective,” says Eimear McBride, “the demands a writer makes on a reader can be perceived as a compliment.”

Related: the following from Geoffrey Hill on “difficulty”:

We are difficult. Human beings are difficult. We’re difficult to ourselves, we’re difficult to each other. And we are mysteries to ourselves, we are mysteries to each other. One encounters in any ordinary day far more real difficulty than one confronts in the most “intellectual” piece of work.

• The Quietus pulled out all the stops this week, interviewing Annette Peacock, Iain Sinclair (again), Alan Moore (again), and asking Peter Strickland, the director of Berberian Sound Studio, for a list of his favourite albums. Given the above, it’s worth noting that all those people have produced challenging work of their own in different media.

• “The Satyrs Motorcycle Club was founded in 1954 with seven members, but little did anyone know it would become the oldest running LGBT organization (and oldest gay motorcycle club) in the world.”

• Trunk TV posted another great selection of television title sequences. The previous selection has been taken down for the usual tiresome copyright reasons so watch this one while you can.

• “Detroit techno and black metal have so much in common,” say Wolves In The Throne Room whose new album, Celestite, is predominantly a product of synthesizer technology.

• “Houghton Library’s copy of Arsène Houssaye’s Des destinées de l’ame (FC8.H8177.879dc) is without a doubt bound in human skin.”

• The secret of Nabokov’s sexual style: David Lodge reviews Nabokov’s Eros and the Poetics of Desire by Maurice Couturier.

• How long can you hold your breath? 2 models, 7 divers in an underwater shipwreck by photographer Von Wong.

• At Dangerous Minds: Paul Gallagher on The fantastic world of Sharmanka Kinetic Theatre.

• Wizards of the Coast: Benjamin Breen on John Dee and the occult in California.

• More photography: Peter Guenzel captures strange lights in forests.

• Mix of the week: Bleep podcast 121 presented by Margot Didsbury.

• I’m The One (1972) by Annette Peacock | Eros Arriving (1982) by Bill Nelson | The Dire And Ever Circling Wolves (2005) by Earth