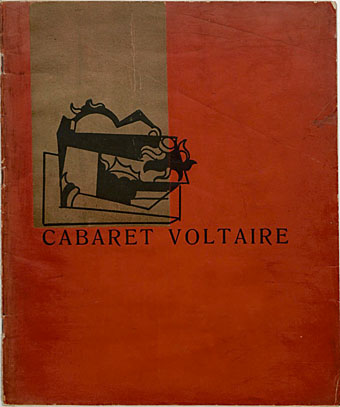

Cabaret Voltaire #1 (1916). Cover by Hans Arp.

Richard H. Kirk’s announcement that he’ll be performing at the Berlin Atonal festival as Cabaret Voltaire caused some raising of eyebrows recently, although if Stephen Mallinder isn’t involved I won’t be getting too excited myself. The last few releases under the Cabaret Voltaire name were credited to Kirk/Mallinder but from Plasticity (1992) on they don’t sound very different to Kirk’s solo releases from the same period. That’s not to say the music suffers but you have to wonder why the group name is being perpetuated if there’s nothing unique attached to it.

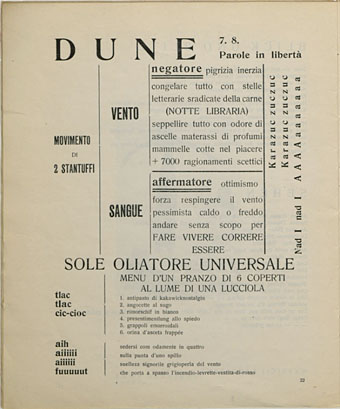

Dune, parole in libertà by Filippo Marinetti.

The group, old or new, will be the first thing that comes to mind for most people when they hear the name Cabaret Voltaire, something that might have surprised Hugo Ball who founded the original Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich almost a century ago. Cabaret Voltaire (the group) named themselves after Ball’s project, their intentions in the mid-1970s being similarly Dadaist. Early Cabs performances were more audience provocations than anything to do with entertainment; the music came later, and only after several years of very uncommercial tape experimentation, some of which can be heard on Methodology ’74–’78: Attic Tapes (2003). Thanks to Switzerland staying out of the war the original Cabaret didn’t get wrecked by bombs or destroyed by the Nazis, and is still active today. Ball also published a Cabaret Voltaire journal, two pages of which can be seen here. If this doesn’t look very dramatic to our eyes it needs to be remembered that everyone who first saw it would have been born in the 19th century so the contents would have seemed a lot more radical. A slim publication but with a formidable list of contributors: Guillaume Apollinaire, Hans Arp, Blaise Cendrars, Wassily Kandinsky, Filippo Marinetti, Amedeo Modigliani, Pablo Picasso, Tristan Tzara and others.

Also at Ubuweb (where else?) there are several recordings of Hugo Ball’s Dada poetry including a recital of Karawane by (of all people) Marie Osmond. Who knew there was a connection between the Osmonds and Cabaret Voltaire?

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Cabaret Voltaire on La Edad de Oro, 1983

• Doublevision Presents Cabaret Voltaire

• Just the ticket: Cabaret Voltaire

• TV Wipeout

• The Crackdown by Cabaret Voltaire