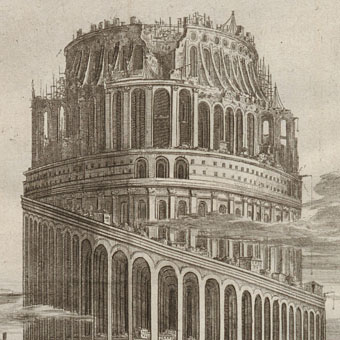

The Tower of Babel (c. 1563) by Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

Seeing as how I have a fetish for Towers of Babel I ought to have examined this one sooner, the copy at the Google Art Project being one which allows you to explore the surface of the picture in greater detail than the artist himself would have seen unless he was using a magnifying glass. I still find the Art Project interface awkward so the grabs here were taken from a massive jpeg at Wikipedia: 30,000 pixels across, or 243 MB, scaling up to around 1.84 GB in Photoshop which means it’ll make older machines grind in complaint.

The detail is astonishing even by Bruegel’s standards. I’d never realised before how much care is given to the individual actions of every single worker on the tower, however small. Bruegel’s close observation of the working habits of the people around him is here reflected in the myriad figures, all of whom are doing something purposeful. At this resolution you’re able to see that the workers have taken their wives and children up the tower with them—there’s the familiar line of washing hung out to dry—while various beasts of burden haul building materials up the spiral roadway. You could spend a long time exploring the details of the tower before even looking at the background where tiny boats are sailing the sea and the rivers, and more fortunate animals have been left to graze in fields.

Wikipedia has several more of these enormous images. It’s a shame there aren’t many more of Bruegel’s works available at this size, his other crowded paintings deserve equal scrutiny.

One of the builders on his lunch break.

A jug on a window sill.