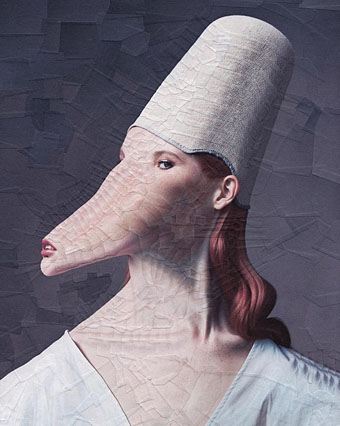

Untitled (2014) by Lola Dupré. Via.

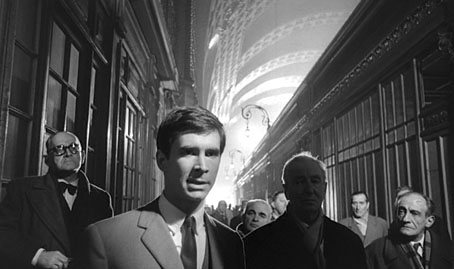

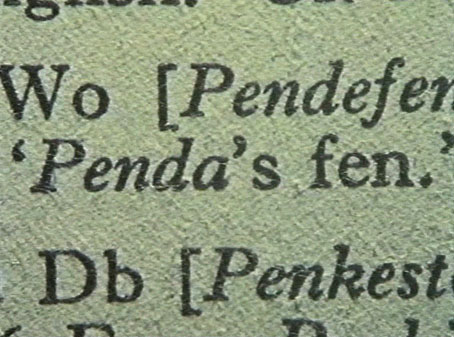

• Announcement of the week (if not the month/year) is the news that the BFI will be releasing all of the BBC dramas directed by Alan Clarke on DVD/Blu-ray in May. In addition to the long-awaited appearance on disc of Penda’s Fen (1974) we can expect a previously unseen director’s cut of Clarke’s last TV film, The Firm (1989), the DVD premier of Baal (1982) with David Bowie, plus many other works including some from the 1960s that were believed lost. (And it should be noted that this isn’t everything of Clarke’s; he also worked occasionally for ITV and later directed feature films for Channel 4.)

The BFI attention is a tribute to an exceptional director that’s overdue. Clarke has long been a cult figure among the British actors who worked with him, and among directors such as Harmony Korine and Gaspar Noé, but the tendency of TV to give one-off dramas a single screening has meant that much of his best work has been unavailable for years outside old VHS tapes. Clarke is important for having persistently chosen difficult subjects which he directed with a flair and intensity usually only found in cinema. When he died in 1990 the BBC repeated a handful of his films but the only ones given repeated DVD release have been the violent dramas with the big names attached: Scum (1979, with Ray Winstone), Made in Britain (1982, with Tim Roth), and The Firm (with Gary Oldman). Clarke’s oeuvre is much more than a parade of nihilistic villains, as will become evident later this year.

• A psychedelic video directed by Peter Strickland for Liquid Gate (ft. Bradford Cox) by Cavern of Anti-Matter. The debut album from Cavern of Anti-Matter, Void Beats/Invocation Trex, will be out later this month.

• Celebrating Dusseldorf, the city that birthed Krautrock. (Article loses points for not mentioning producer Conny Plank.)

All Rivette’s features might be regarded as different kinds of horror films; Céline et Julie vont en bateau is his first horror comedy. The anxiety and despair of Paris Nous Appartient and La Religieuse, L’Amour Fou and Spectre seem relatively absent, yet they perpetually hover just beyond the edges of the frames. We still have no privileged base of ‘reality’ to set against the fictions, each of which is as outrageous as the other; and along with Borges, we can’t really say whether it’s a man dreaming he’s a butterfly or a butterfly dreaming he’s a man—although we may feel, in either case, that he and we are just on the verge of waking.

Jonathan Rosenbaum on work and play in the house of fiction: Jacques Rivette’s Out 1 and Céline and Julie Go Boating

• Mixes of the week: Finders Keepers Radio Show Krautrock Special, and The Ivy-Strangled Path Vol. XV by David Colohan.

• At Dangerous Minds: Super strange sculptures (by Shary Boyle) only the dark and demented could love.

• Beautiful Brutalites: S. Elizabeth questions Arabella Proffer about her paintings.

• KTL is a musical collaboration between Peter Rehberg and Stephen O’Malley.

• Why study art when you can make it? The strange world of…This Heat.

• Sarah Galo on the explicitly sexual female artists that feminism forgot.

• Irmin Schmidt‘s favourite music (this week).

• LSD: My life-saving drug by Eric Perry.

• Der LSD-Marsch (1970) by Guru Guru | Krautrock (1973) by Faust | Düsseldorf (1976) by La Düsseldorf