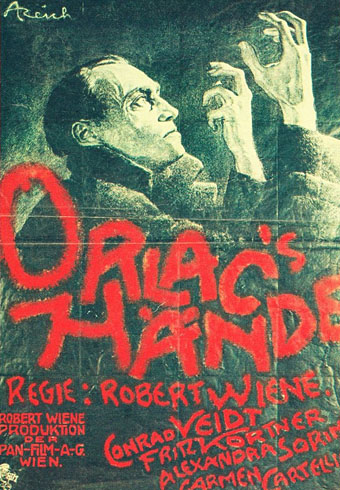

My weekend viewing included two films based on The Hands of Orlac (1920), a novel by Maurice Renard. This is one of those books that remains little read and seldom discussed even though its central idea—a concert pianist injured in a train wreck is given the hands of an executed murderer in a transplant operation—has prompted many film adaptations, almost enough to make the novel the origin of a sub-genre of hand-transplant horror. Robert Wiene’s The Hands of Orlac was the first screen adaptation made in 1924, and is another in the long list of silent films I’ve known about for decades but had to wait until now to see. The film is notable for reuniting the director of The Cabinet of Dr Caligari with Conrad Veidt, the actor who portrayed Caligari’s murderous somnambulist, Cesare, in a mute role that mostly required stalking around acutely-angled sets in a black body stocking.

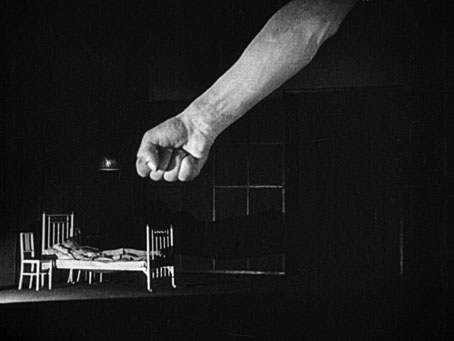

The Hands of Orlac: Paul Orlac (Conrad Veidt) is besieged by nightmares in his colossal hospital room.

Veidt has much more to do as the lead in The Hands of Orlac, giving a suitably tormented performance as the pianist convinced that his new hands retain the violent impulses of their former owner. The acting from Veidt and Alexandra Sorina as Orlac’s wife, Yvonne, is often wildly emotive, surprisingly so for a film made near the end of the silent era when the mannerisms of early silent pictures were being replaced by greater naturalism. Lotte Eisner in The Haunted Screen explains this in terms of the Expressionist influence which was still prevalent in German cinema, and which extends beyond lighting and set design. A scene in which Orlac is overwhelmed by his predicament is described by Eisner as “an Expressionist ballet”; when Orlac holds a dagger aloft this becomes an unmistakable mirroring of a climactic moment in Caligari.