The Tower of Babel from Turris Babel (1679) by Athanasius Kircher, showing how wide the Tower would have to be at its base to reach the Moon.

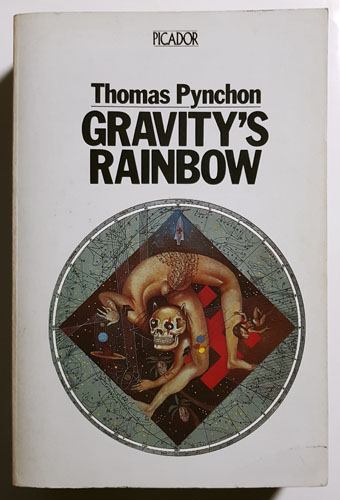

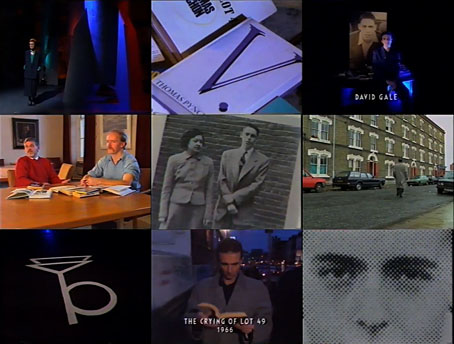

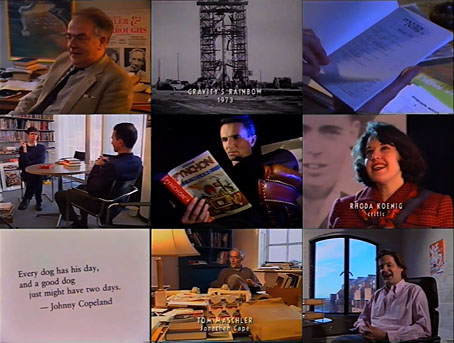

• The week’s literary resurrection: Penguin announced Shadow Ticket, a new novel by Thomas Pynchon. “Hicks McTaggart, a one-time strikebreaker turned private eye, thinks he’s found job security until he gets sent out on what should be a routine case, locating and bringing back the heiress of a Wisconsin cheese fortune who’s taken a mind to go wandering…”

• The week’s musical resurrection: Stereolab announced Instant Holograms On Metal Film, their first new album since Not Music in 2010. Aerial Troubles is the new single with a video which has prompted complaints in the comments about the use of AI treatments for the visuals.

• At Public Domain Review: Modern Babylon: Ziggurat Skyscrapers and Hugh Ferriss’ Retrofuturism, a long read by Eva Miller. Previously: The Metropolis of Tomorrow by Hugh Ferriss.

• This week in the Bumper Book of Magic: Ben Wickey is selling some of the original art from his Lives of the Great Enchanters pages.

• At Wormwoodiana: The Golden Age of Second-Hand Bookshops is now. Mark Valentine explains.

• “Alvin Lucier is still making music four years after his death – thanks to an artificial brain.”

• At Colossal: Hundreds of fantastic creatures inhabit a sprawling universe by Vorja Sánchez.

• Coming soon from Radiance Films: A blu-ray disc of Essential Polish Animation.

• Pattern design and illustration by Gail Myerscough.

• Steven Heller’s font of the month is Homage Script.

• New music: Sabi by Odalie.

• RIP Max Romeo.

• Babylon (1968) by Dr John | War In A Babylon It Sipple Out Deh (1976) by Max Romeo | Babylonian Tower (1982) by Minimal Compact