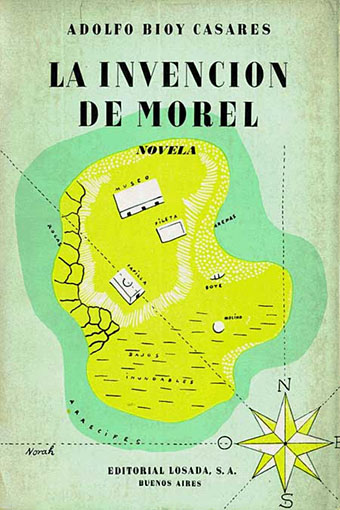

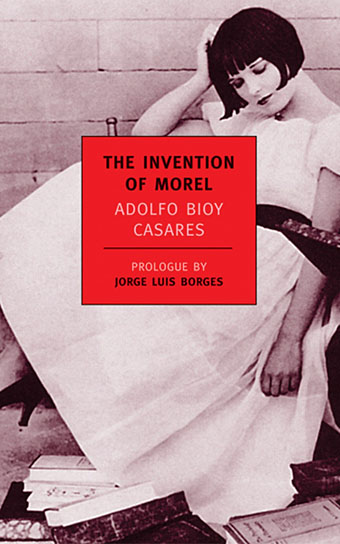

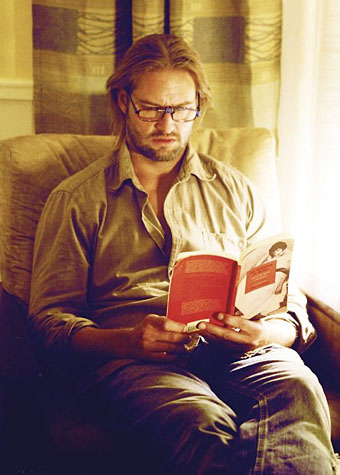

1: The Invention of Morel (1940), a novel by Adolfo Bioy Casares.

Cover art by Norah Borges.

A fugitive hides on a deserted island somewhere in Polynesia. Tourists arrive, and his fear of being discovered becomes a mixed emotion when he falls in love with one of them. He wants to tell her his feelings, but an anomalous phenomenon keeps them apart. (more)

Jorge Luis Borges declared The Invention of Morel a masterpiece of plotting, comparable to The Turn of The Screw and Journey to the Centre of the Earth. Set on a mysterious island, Bioy’s novella is a story of suspense and exploration, as well as a wonderfully unlikely romance, in which every detail is at once crystal clear and deeply mysterious. Inspired by Bioy Casares’s fascination with the movie star Louise Brooks, The Invention of Morel has gone on to live a secret life of its own.

Octavio Paz:

The Invention of Morel may be described, without exaggeration, as a perfect novel….Bioy Casares’s theme is not cosmic, but metaphysical: the body is imaginary, and we bow to the tyranny of a phantom. Love is a privileged perception, the most complete and total perception not only of the unreality of the world but of our own unreality: not only do we traverse a realm of shadows, we ourselves are shadows.

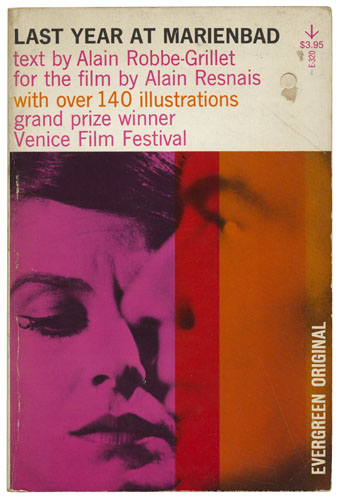

2: Last Year at Marienbad (1961), a feature film directed by Alain Resnais.

Alain Robbe-Grillet, Sight and Sound, Autumn 1961:

What are these images, actually? They are imaginings; an imagining, if it is vivid enough, is always in the present. The memories one “sees again”, the remote places, the future meetings, or even the episodes of the past we each mentally rearrange to suit our convenience are something like an interior film continually projected in our own minds, as soon as we stop paying attention to what is happening around us. But at other moments, on the contrary, all our senses are registering this exterior world that is certainly there. Hence the total cinema of our mind admits both in alternation and to the same degree the present fragments of reality proposed by sight and hearing, and past fragments, or future fragments, or fragments that are completely phantasmagoric.

Rosetta Stone to Last Year in Marienbad:

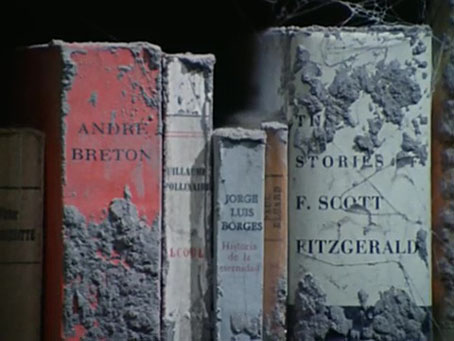

In the mid-Fifties, when Casares’ novel was translated into French, it was read by Robbe-Grillet. We know this since he wrote a favorable review of the book in 1955. In 1961, Resnais and Robbe-Grillet were interviewed by filmmaker Jacques Rivette, who commented on the link between Morel and Marienbad, parallels briefly acknowledged by Robbe-Grillet (who didn’t elaborate). Resnais and Robbe-Grillet had evidently never discussed this, as indicated by Resnais’ comment that he was unfamiliar with the book! An English translation of this interview was readily available to all New York critics in 1961, but none of them picked up on the significance of those few sentences.

Louise Brooks, Delphine Seyrig.

Ann Manov, The Invention of Marienbad: Resnais, Robbe-Grillet, Morel, and Adolfo Bioy Casares on the Left Bank:

L’Année dernière à Marienbad (1961) is an adaptation that became a theft. It is plainly based on La Invención de Morel (1940), and this was immediately apparent to the critics who first viewed it. The Cahiers du cinéma that came out with Marienbad is full of references to Morel, of critics saying how immediate the connection was. And on a biographical level, it’s pretty obvious: in 1953, the screenwriter Alain Robbe-Grillet asked his editor at Critique magazine if he could write about an interesting Argentinean novel; he wrote an admiring but mixed review about the importance of the themes of solitude, memory, and the modifiable past, and how he hoped another artist could do them more justice; and seven years later, he wrote a screenplay with the same setting, characters, motifs, and themes, complete with, in first drafts, Hispanic names.

But the orthodox view about this connection, on the exceedingly rare occasions it is mentioned outside of the Hispanic world, is summarily dismissive: as a recent master’s thesis summarizes, “Since the release of Last Year at Marienbad in 1961, some critics have taken to circumventing the difficulty of the film by drawing on The Invention of Morel as the alleged inspiration for the film.”

Without Morel, Marienbad is mostly an exercise in formalism; however, with the intertextual juxtaposition of the two, it becomes another, different work. It becomes an early false reality film, perhaps the first.

3: L’invention de Morel (1967), a TV film directed by Claude-Jean Bonnardot.

• The entire film on YouTube (with English subtitles).

4: Celine and Julie Go Boating (1974), a feature film directed by Jacques Rivette.

When we discussed how the second film should be integrated with the first, we considered various possibilities. At one stage the idea was to go much further in fragmenting the second film, particularly in dispersing the various elements, letting the montage range freely, thus permitting a variety of different meanings. At this point, naturally, we thought of Comedie Policiere and about a writer who has been much in view since L’Année dernière à Marienbad (and even before): Adolfo Bioy Casares and his novel The Invention of Morel. Of course we knew all this existed—Marienbad and the TSE and The Invention of Morel—but we were trying to find a motif for ourselves which would be both similar to theirs and at the same time different…

5: L’invenzione di Morel (1974), a feature film directed by Emidio Greco.

• The entire film on YouTube (Italian only).

6: The Invention of Dr Morel (2000), a short film directed by David Lamelas.

7: Lost (2004–2010), a TV series.

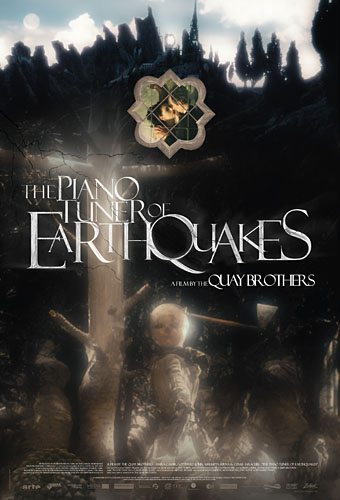

8: The Piano Tuner of Earthquakes (2005), a feature film directed by the Quay Brothers.

Virginie Sélavy: Was The Invention of Morel an influence?

The Quay Brothers: Yeah, it was very important. We couldn’t get the rights for it. We actually wrote to Adolfo Bioy Casares and he said, “sure, you can have it”, and then he wrote back a day later and he said, “I forgot, I gave it to somebody else”. (laughs) We found out that this guy, some Argentinean in Paris who’s had it for thirteen years, never got it off the ground but keeps renewing the rights. So Alan [Passes, co-writer of Piano Tuner] and the two of us said, well, let’s just work around the themes a little bit. So all you really have is the island, the tide, elements like that.

VS: I thought you also kept the idea of people being replaced by their images and living this kind of eternal but illusory, disembodied life.

QQ: Yes, exactly. Perpetuum mobile almost, because at the very end the character in The Invention of Morel asks that if anybody should invent a machine capable of reuniting their images, they help him enter into Faustine’s consciousness, which is a little bit what the Felisberto character is attempting at the end of Piano Tuner. He claims to have succeeded—he says, “we’re together, buried among the rocks”. In his imagination at least he’s done it. The Invention of Morel was actually a homage to Louise Brooks—Faustine really is Louise Brooks. Bioy Casares was fascinated by her.

VS: And there’s also the character of the mad inventor.

QQ: Yes, I think he features less in The Invention of Morel, he’s more like a shadow figure. (more)

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Marienbad hauntings