The Crystal Ball (c. 1900) by Robert Anning Bell.

Crystal balls in art, film and the pulp magazines.

The Crystal Ball (1902) by John William Waterhouse.

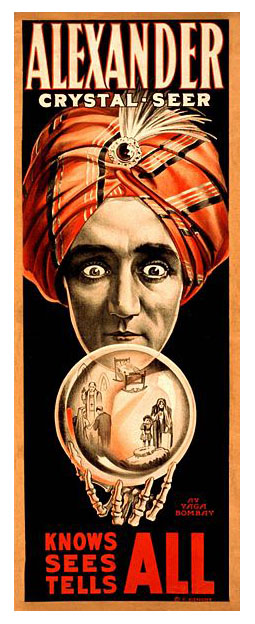

Alexander, Crystal Seer (1910).

A journal by artist and designer John Coulthart.

The Crystal Ball (c. 1900) by Robert Anning Bell.

Crystal balls in art, film and the pulp magazines.

The Crystal Ball (1902) by John William Waterhouse.

Alexander, Crystal Seer (1910).

Salome (1918) souvenir book.

A few of the Salomés recently added to the Google Art Project. The painting by Andrea Ansaldo shows a head that looks distinctly unwell, something that’s not so common in the world of glow-in-the-dark saints. Ansaldo’s Salomé, meanwhile, is so young and diminutive that she hardly seems capable of holding the platter. One way in which this particular theme has survived for so long is that the narrative thread is the sole thing that connects the many variations, all other details are open to interpretation.

Below there’s a more recent painting by Izabella Gustowska that makes the inevitable connection between Salomé and her Biblical sister, Judith.

Herodias Presented with the Head of the Baptist by Salomé (c. 1630) by Andrea Ansaldo.

Salomé (1870) by Henri Regnault.

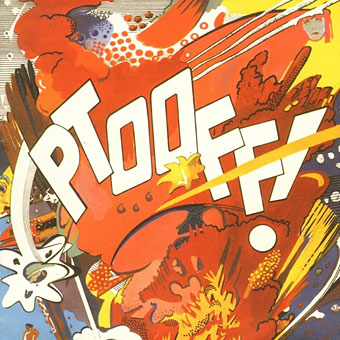

There’s a sub-genre of the psychedelic album cover in which florid, unfocused and vividly polychrome doodles by friends of the band are used as the principal artwork. (The cover of The Parable Of Arable Land [1967] by The Red Crayola is a typical example.) The art which decorates the fold-out sleeve of Ptooff! (1967), the debut album by British group The Deviants, isn’t quite in the doodle league but it treads a narrow divide between drug-addled scribbles and American comic-strip art à la Jack Kirby. Someone named “Kipps” receives the art credit. Viewed today the swirls and explosions on the sleeve’s outer panels also seem to predict the graffiti art which would flourish a decade later.

The Deviants were the first musical vehicle for writer and singer Mick Farren who died last week. At the time Farren was known as a journalist for International Times which explains the disembodied head of Theda Bara (from the paper’s logo) floating in the top right-hand corner of the front cover. The lysergic wildness continues inside with an incoherent scene and the promise that “APSARAS—is an Epic forthcoming—a marvel of the Universe—an illustrated saga of a Godwoman. On sale soon.” John Peel provided some sleeve notes. See the artwork at larger size here.

Charles Shaar Murray penned a memorial note for Mick Farren last week. My favourite track from Ptooff! is the opening song I’m Coming Home, a number that demonstrates the group’s ability to combine humour with hard-rock freakout.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The album covers archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• International Times archive

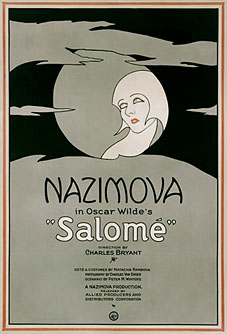

Salome (1918).

You can’t keep a bad girl down… Attempting to gather all the painted representations of Salomé would be a foolish enterprise, there are far too many especially when you reach the 19th century, an age whose misogyny found an ideal expression in the emasculating temptress. Searching through 20th century adaptations yields some interesting works, however.

Theda Bara’s film pre-dates the more flamboyant Nazimova version by five years, and since I haven’t seen it I’ve no idea how it holds up today. But from the look of the stills and posters it seems far closer to the usual historical fare than the stylised version which followed.

We tend to think of cinema as a modern medium, quintessentially 20th century, but the modern medium was born in the 19th century, and the heyday of the Silent Age (the 1920s) was closer to the Decadence of the fin de siècle (mid-1880s to the late-1890s) than we are now to the 1970s. This is one reason why so much silent cinema seems infected with a Decadent or Symbolist spirit: that period wasn’t so remote and many of its more notorious products cast a long shadow. Even an early science fiction film like Fritz Lang’s Metropolis has scenes redolent of late Victorian fever dreams: the vision of Moloch, Maria’s parable of the tower of Babel, the coming to life of statues of the Seven Deadly Sins, and—most notably—the vision of the Evil Maria as the Whore of Babylon. Woman as vamp or femme fatale was an idea that gripped the Decadent imagination, and it found a living expression in the vamps of the silent era, beautiful women with exotic names such as Pola Negri, Musidora (Irma Vep in Feuillade’s Les Vampires) and the woman the studios and press named simply “the Vamp”, Theda Bara (real name Theodosia Burr Goodman).

We tend to think of cinema as a modern medium, quintessentially 20th century, but the modern medium was born in the 19th century, and the heyday of the Silent Age (the 1920s) was closer to the Decadence of the fin de siècle (mid-1880s to the late-1890s) than we are now to the 1970s. This is one reason why so much silent cinema seems infected with a Decadent or Symbolist spirit: that period wasn’t so remote and many of its more notorious products cast a long shadow. Even an early science fiction film like Fritz Lang’s Metropolis has scenes redolent of late Victorian fever dreams: the vision of Moloch, Maria’s parable of the tower of Babel, the coming to life of statues of the Seven Deadly Sins, and—most notably—the vision of the Evil Maria as the Whore of Babylon. Woman as vamp or femme fatale was an idea that gripped the Decadent imagination, and it found a living expression in the vamps of the silent era, beautiful women with exotic names such as Pola Negri, Musidora (Irma Vep in Feuillade’s Les Vampires) and the woman the studios and press named simply “the Vamp”, Theda Bara (real name Theodosia Burr Goodman).

Alla Nazimova was another of these exotic creatures, and rather more exotic than most since she was at least a genuine Russian, even if she also had to amend her given name (Mariam Edez Adelaida Leventon) to exaggerate the effect. Like an opera diva or a great ballerina she dropped her forename as her career progressed, and is billed as Nazimova only in her 1923 screen adaptation of Oscar Wilde’s play, Salomé. Nazimova inaugurated the project, produced it and even part-financed it since the studios, increasingly worried by pressure from moral campaigners, regarded it as a dangerously decadent work. Nazimova had a rather colourful off-screen life and the stories of orgiastic revels at her mansion, the Garden of Allah, probably didn’t help matters.

Salomé lobby card (1923).