If you’re an obsessive cineaste there’s a good chance you maintain a mental list of the films you’d like to see, the films you’d like to see again, and the films you’d like to see reissued on DVD. The vagaries of distribution and ownership often conspire to make older films fall out of sight even when they’ve been produced and promoted by major studios, have had TV screenings and so on. This was famously the case with five of Alfred Hitchcock’s features—Vertigo and Rear Window among them—which managed to remain out of circulation for two decades; more notoriously there was Stanley Kubrick’s neurotic embargo on any screening of A Clockwork Orange in the UK which meant that my generation of Kubrick-watchers had to make do with a variety of pirate VHS recordings.

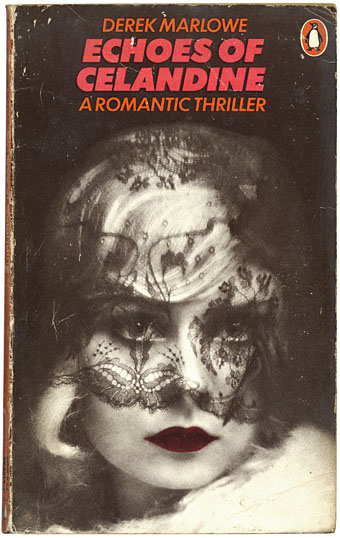

Penguin edition, 1973. Photo by Van Pariser.

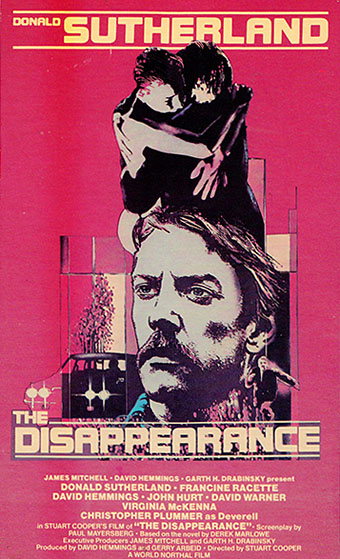

DVD reissues have chipped away at my “must see again” list with the result that Stuart Cooper’s The Disappearance (1977) recently found itself at the top of the catalogue. This film has never been as inaccessible as some: it received at least two TV screenings in the UK, and was available on VHS cassette for a time. There was also a DVD release although by the time I started looking for it the only available copies were secondhand ones commanding high prices. A year or so ago I read Derek Marlowe’s Echoes of Celandine (1970), the novel on which the screenplay is based, and as a result became more eager than ever to see the film again. Having finally watched a very poor-quality transfer of a VHS copy on YouTube I now feel sated, even if the experience was unsatisfying.

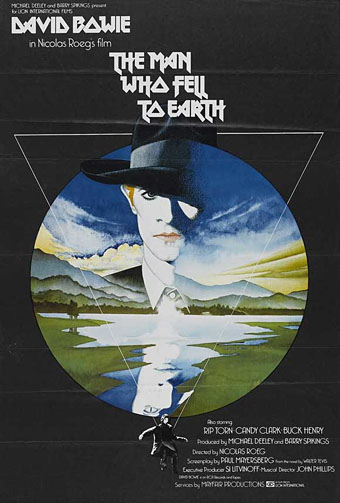

The Disappearance is one of those odd productions that ought to have all the ingredients to make a very memorable film but which never works as well as you might hope. The screenplay was by Paul Mayersberg, written between his two films with Nicolas Roeg, The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976) and Eureka (1983); there’s a great cast: Donald Sutherland, David Warner, Peter Bowles, David Hemmings (who also produced), John Hurt, Virginia McKenna, Christopher Plummer; Kubrick’s cameraman of the 1970s, John Alcott, photographed the film shortly after winning an Oscar for his work on Barry Lyndon; the source material is very good: Marlowe’s novel is described as “a romantic thriller” but when the quality of the writing easily matches any literary novels of the period such a description makes it sound more generic and pot-boiling than it is.

Continue reading “The Disappearance, a film by Stuart Cooper”