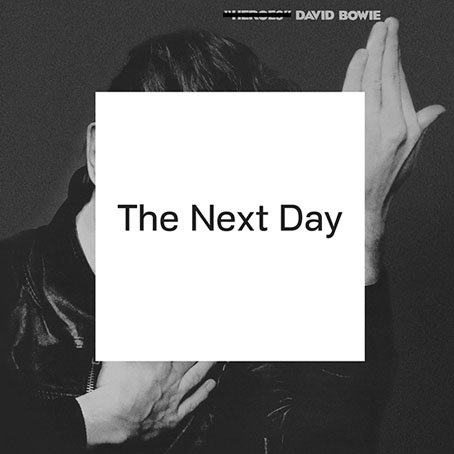

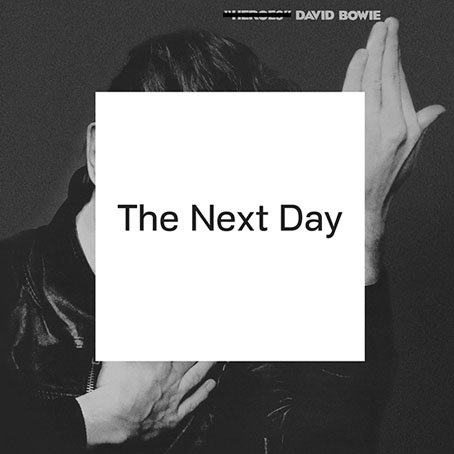

Gratifying this week to see album cover art under discussion even if the heat-to-light ratio was as unbalanced as it usually is when pop culture is the subject. Jonathan Barnbrook, who also designed the Heathen (2002) and Reality (2003) packaging for David Bowie, wrote about the thinking behind the new cover on his blog. (And for the time being let’s note that this is still only a cover design, we don’t know what else is on its way.)

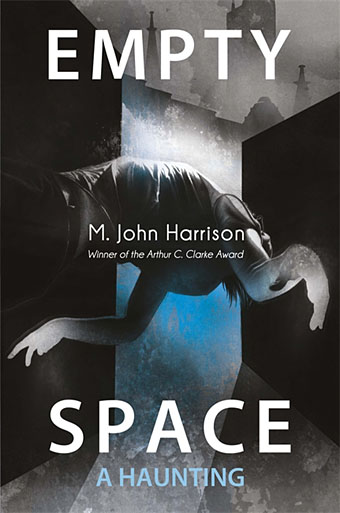

For my part I’ll point out that the artist-as-cover-image is the great cliché of album design, and the bigger the name the more the rule applies; Neville Brody complains about this in the first book of his work, as does Storm Thorgerson in the Hipgnosis books. In Bowie’s case the rule has been applied almost universally since his debut album in 1967, the only variations being illustrational ones or slight dodges like having his feet appear on the front of Lodger and his back facing the viewer on Earthling. Consequently the new design is a radical gesture from an artist who could have got away with a photo of himself du jour. By way of contrast, consider that Rod Stewart is a year older than David Bowie and presented the world with this artefact in October 2012.

Related: Hard Format responds to the cover, Chris Roberts on “Picasso resurrected in a Rolf Harris era“, and Alexis Petridis on The inside story of how David Bowie made The Next Day.

• The Quicksilver typeface, designed by Dean Morris when he was only 16, bought by Letraset and now an indelible feature of pop design from the 1970s. Morris describes his experience here (“they shunned rapidographs!”) and collects examples of the print history here.

When the days are short, we are closest to the medieval world. To the avoidance of mirrors where death improves our portraits every morning with a few more lines and shadows. What would once have been a sermon, a conjuring of hellfire, a phantom slide show, is now an entertainment. But before we can begin again, we have to kick free of the embrace of our inconvenient predecessors, that compost legion of the anonymous dead. They come uninvited, requiring us to sign up for what the late Derek Raymond called the general contract: a brief turn in the light, then extinction. Eternal darkness. How to live with such knowledge? William Burroughs admired the unswerving bleakness of Beckett’s gaze, the way he reduced compensatory illusions to zero. Nowhere left to crawl. And nothing to crawl on. Last breath is last breath. Stare into the abyss and the abyss will stare right back.

Iain Sinclair reviews The Undiscovered Country: Journeys Among the Dead by Carl Watkins

• Broadcast’s James Cargill on Morricone, Minidiscs and Scoring Berberian Sound Studio. Related: Melmoth the Wanderer posts a new mix, The Curious Episode of the Wizard’s Skull, and more spooky sounds are on their way from The Haxan Cloak.

• A Firm Turn Toward the Objective: Joanne Meister on meeting the great Swiss designer Josef Müller-Brockmann.

Twitter user @thisnorthernboy reworked Paul Emsley’s portrait of Kate Middleton. @barnbrook approved.

• The Beatles of Comedy: David Free on the Monty Python team.

• The history of the London Underground poster.

• Impossible Architecture by Filip Dujardin.

• At Pinterest: Art Dolls & Sculpture

• Grace Jones’ Nightclubbing album has been on repeat play this week: Warm Leatherette/Walking In The Rain | I’ve Seen That Face Before (Libertango) | Demolition Man