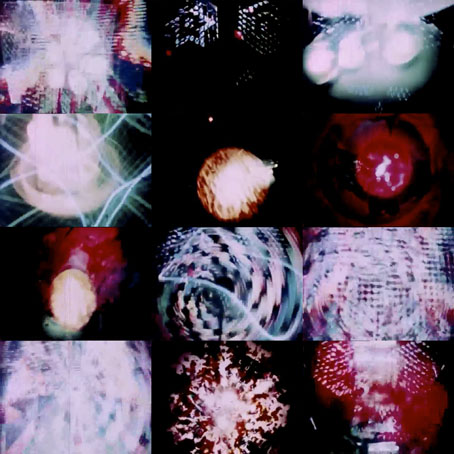

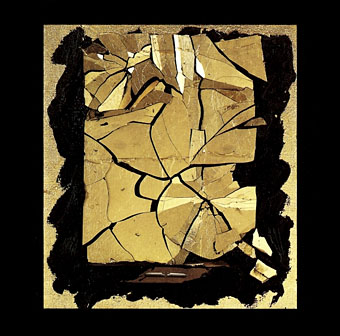

Cover of How To Destroy Angels (Remixes And Re-Recordings) (1992) by Coil. Artwork: Fine Balance (1986) by Derek Jarman.

• It’s that man again: “According to the late great short story writer Robert Aickman, the problem with our excessively modern world is not that it is strange, but that it is not strange enough.” Scott Bradfield on a writer who can no longer be described as neglected or overlooked.

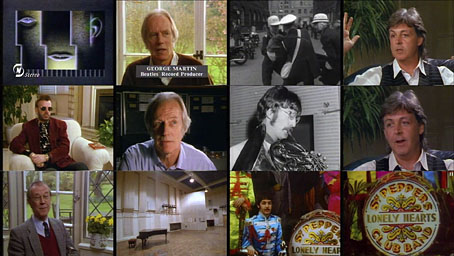

• Coil may have expired over a decade ago after the death of John Balance but the posthumous releases persist. Latest of these is How To Destroy Angels, an album-length presentation of music (or audio) by Coil and Zos Kia (John Gosling) from 1983/84.

• “Two decades ago, a renowned professor promised to produce a flawless version of one of the 20th century’s most celebrated novels: Ulysses. Then he disappeared.” The Strange Case of the Missing Joyce Scholar.

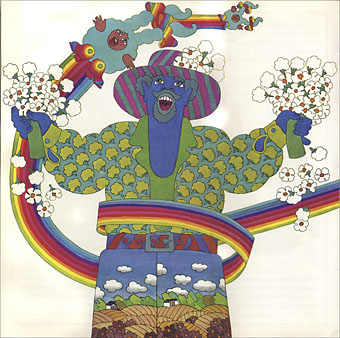

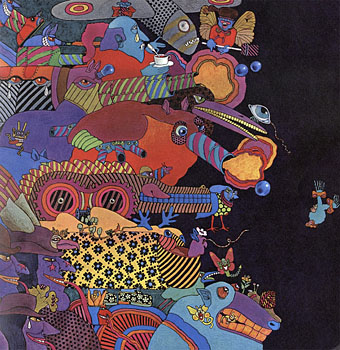

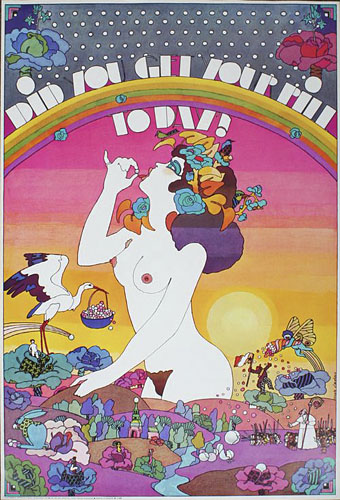

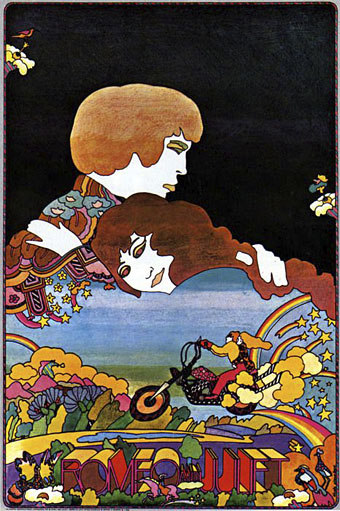

• At Dangerous Minds: The Fool: The Dutch artists who worked for The Beatles (and made their own freak folk masterpiece). Previously here: The art of Marijke Koger.

• RIP Nick Knox. The Cramps were always best when playing live, as here in 1986 when they performed songs from A Date With Elvis on Channel 4’s The Tube.

• “The McKenzie Tapes is a collection of live audio recordings from some of New York City-area most prominent music venues of the 1980s and 1990s.”

• Beyond the veil: two extracts from Death by Anna Croissant-Rust, one of two new books from Rixdorf Editions.

• Impulse Responses: composer Deru on scoring with the Cristal Baschet.

• Fleshback: Queer Raving in Manchester’s Twilight Zone Chapter 1–3.

• “Puzzler says he has cracked code to stolen Belgian masterpiece.”

• Mix of the week: FACT mix 657 by Beatrice Dillon.

• Jenzeits

• Death Have Mercy (1959) by Vera Hall | Oh Death (1964) by Dock Boggs | Oh Death (1967) by Kaleidoscope