Mouse Heaven: Minnie and Mickey.

Kenneth Anger’s paean to Disney rodent memorabilia, and one of his most recent works, turns up at the Grey Lodge. Mouse Heaven is a distinctly minor piece, an awkward mix of film and video which juxtaposes shots of mouse figurines with a song-based soundtrack. Scorpio Rising this isn’t but the editing is up to his usual standard, and it has a curious, if rather grotesque, charm.

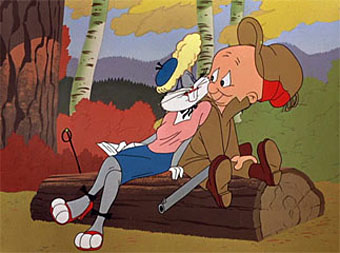

Rabbit heaven: Bugs drags up again.

I suspect I’m not the ideal audience for a film such as this, never having been very taken with Mickey and the rest of the Disney crew. This seems to be a generational thing. My parents are about Anger’s age and they watched Disney shorts regularly at the cinema, while older Americans would have seen the Mickey Mouse Club on TV in the 1950s. By the time my sisters and I were watching cartoons on television Disney had retreated into the pop culture background. Plenty of merchandise was available, of course, but the animations that gave birth to these characters were rarely seen on British TV since Disney was worried about over-exposure of their precious assets.

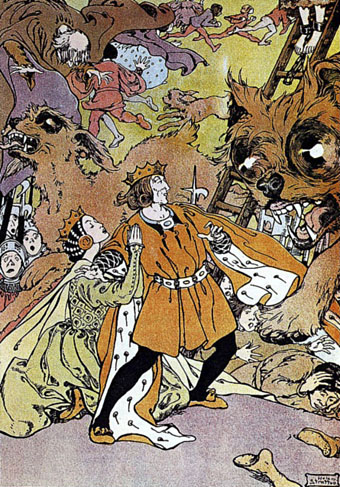

The consequence of this (which I doubt they realised) was that a new generation of kids could happily and eagerly watch all the Warner Brothers Merry Melodies (and MGM’s Tom & Jerry and Tex Avery cartoons) whereas I’ve still seen very few Mickey Mouse cartoons. Those that did turn up were either primitive (Steamboat Willie) or presented a Mouse character that was actually a suburban middle-class American. The contrast between Donald Duck’s irritating petulance and Daffy’s wisecracks, or between the Mouse in a house and a bisexual rabbit, could hardly be more striking. The last shred of any potential Disney charm was dispelled when I read the priceless demolition of Disneyworld and its inhabitants, Mickey Rodent!, by Harvey Kurtzman and Will Elder, in a reprint of MAD magazine:

Strolling in the foreground of the opening panel is Mickey himself, with a four-day stubble on his face and a snapped mouse trap on his snout; his left arm has a TV screen, smashed in the middle, with “Howdy Dooit” sunrays visible. (That’s an inside joke: in a previous issue, parodying “Howdy Doody,” Mickey was seen at the edge of the opening panel, grasping and shouting, “That’s MY sunray from MY movies behind his head and I wannit back!”) Around him a melodrama unfolds: Horace Horszneck is being dragged off to jail “for appearing without his white gloves.” The animal chorus behind him clucks, moos and barks their annoyance with “Walt Dizzy’s” rule about wearing white gloves at all times… “In this hot weather too!” “And it’s so hard to buy those furshlugginer three-fingered kinds!” (Read the rest of the description here and try and see the comic for yourself; it’s a masterpiece.)

There was no going back after that, and Wally Wood’s Disneyland Memorial Orgy was merely the icing on an already mouldering cake. So, sorry Kenneth, but I’m an apostate; Bugs Bunny rules my blue heaven.

• The Look traces the history of Wally Wood’s scurrilous poster from hippie to punk to Alison Goldfrapp

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Man We Want to Hang by Kenneth Anger

• Relighting the Magick Lantern

• The Realist

• Kenneth Anger on DVD…finally