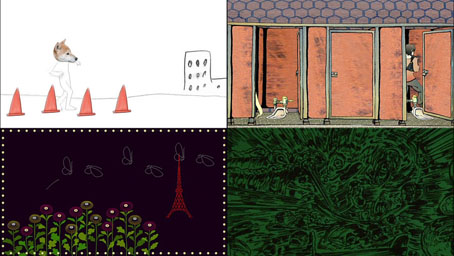

Tokyo Strut (Masahiko Sato, Mio Ueta), Tokyo Trip (Keiichi Tanaami)

Fishing Vine (Mika Seike), Yuki-chan (Kei Oyama).

Search for the phrase “Tokyo Loop” and you’ll be offered information about the Yamanote rail line which runs in a circle through Japanese capital. The Loop that concerns us here is very different, a collection of 16 short films made in 2006:

Tokyo’s centre for experimental and art cinema, Image Forum, under the guidance of program director Takashi Sawa and coordinator Koyo Yamashita, has a knack for putting together some clever screening packages together for the Image Forum Festival every year. Many of these packages, such as Thinking and Drawing, make their way into international festivals, and in some cases even onto DVD. Such is the case with the 2006 omnibus Tokyo Loop featuring the work of both established artists like Yoji Kuri, Taku Furukawa, Keiichi Tanaami, Nobuhiro Aihara, as well as exciting younger artists such as Kei Oyama, Mika Seike, Tabaimo, and Tomoyasu Murata.

Tokyo Loop came out of Image Forum’s desire to do something to celebrate the hundredth anniversary of Stuart Blackton’s animation “Humorous Phases of Funny Faces” (1906), considered by many the first publicly screened animated film. Sawa and Yamashita commandeered the help of Furukawa who contributed to the project with a film of his own and helped recruit other independent animation and experimental artists.

The 16 artists were asked to contribute a short film inspired by the city of Tokyo. The films would also be linked by the participation of Seiichi Yamamoto, a well-known musician from Osaka’s underground music scene who composed the score. Yamamoto corresponded with the artists during the production process. He composed the music in advance based upon the sketches and storyboards provided by each animator, then revised them to fit the final edit of the film. (more)

Dog & Bone (Kotobuki Shiriagari), Public Convenience (Tabaimo)

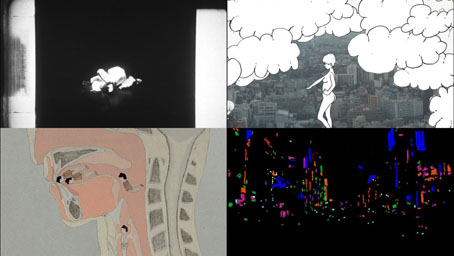

Tokyo (Atsuko Uda), Black Fish (Nobuhiro Aihara).

Everything in the collection is animated to some degree but the experimental factor dominates, with the films running through a range of different styles and techniques. I especially enjoyed Tokyo Strut, a minimal display of wireframe animation; and Nuance, a film where nocturnal drives through city streets are presented with flickering rotoscoped shapes and colours.

Unbalance (Takashi Ito), Tokyo Girl (Maho Shimao)

Manipulated Man (Atsushi Wada), Nuance (Tomoyasu Murata).

All the films are wordless, with scores that run through a variety of musical styles, from abrasive noise and glitchy electronics to simple melodies played with guitar and synthesizer. I didn’t recognise Seiichi Yamamoto‘s name at first but he’s a versatile and prolific musician whose collaborations with other artists (Boredoms among them) are copious enough for him to be lurking on some of the Japanese CDs on my shelves. One of his own bands, Omoide Hatoba, released Kinsei in 1996, an album I bought when it was released but have never played very much. Time to give it another airing.

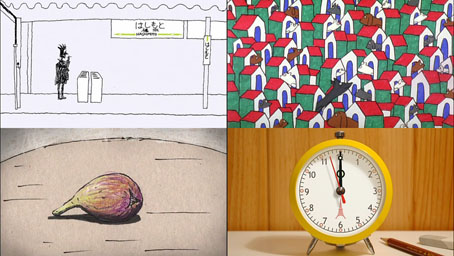

Hashimoto (Taku Furukawa), Funkorogashi (Yoji Kuri)

Fig (Kouji Yamamura), 12 O’Clock (Toshio Iwai).

Previously on { feuilleton }

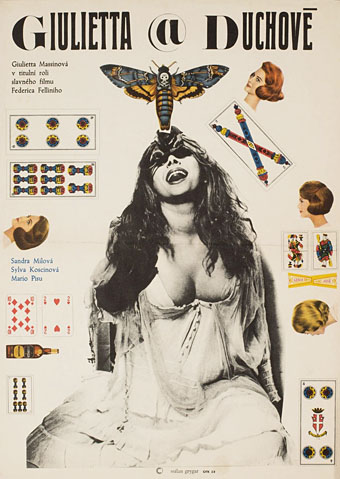

• Chirico by Tanaami and Aihara

• The Midnight Parasites by Yoji Kuri

• Sweet Friday, a film by Keiichi Tanaami

• Tadanori Yokoo animations