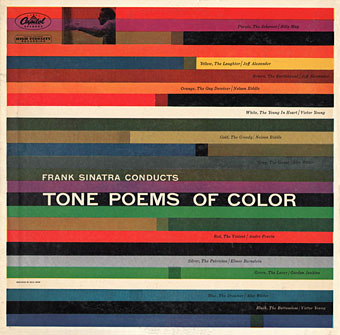

Frank Sinatra Conducts Tone Poems Of Color (1956).

The great designer and filmmaker Saul Bass is the subject of renewed attention with the publication this month of Saul Bass: A Life In Film & Design by Jennifer Bass and Pat Kirkham, the first comprehensive examination of the man’s work. A post at AnOther has an extract from Martin Scorsese’s foreword, and also a small selection of designs from the book among which was this tremendous Sinatra album cover that I’d not seen before. The album was a limited edition release in which a number of Sinatra’s composer friends produced pieces of music based on colour-themed poems by Norman Sickel. Sinatra had appeared in Otto Preminger’s The Man With the Golden Arm the year before, the film for which Saul Bass designed a title sequence and a poster that’s probably more visible (and imitated) these days than the film itself. (The arm from the poster is the main graphic on the cover of the new book.) Bass designed the posters, titles and ads for many other Preminger films, more than for any other director. A number of those films had soundtrack albums, of course, as did other films featuring Bass’s work. Usually the poster design was adapted for the album sleeve (something you can see at this Flickr set) but the Sinatra album had me wondering whether there were more albums with Saul Bass covers that aren’t film spin-offs.

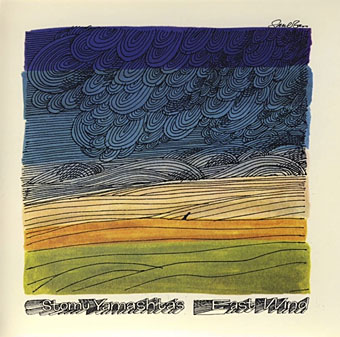

Freedom Is Frightening (1973) by Stomu Yamash’ta’s East Wind.

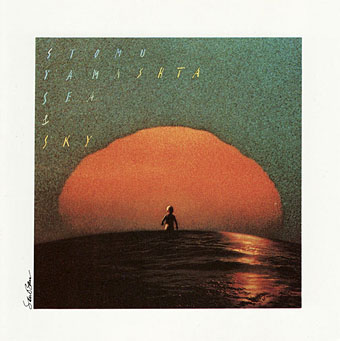

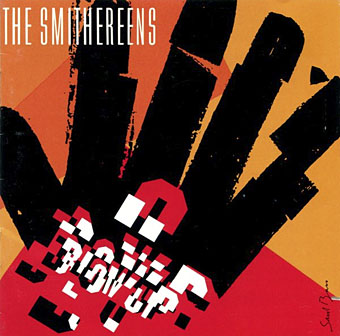

Searching around turned up a few more surprises: two covers a decade apart for Japanese jazz musician Stomu Yamash’ta, and a one-off for The Smithereens who were audacious enough to ask for a cover design in 1991, right at the time when Bass’s work was being noticed again thanks to Martin Scorsese. Outside of the soundtrack albums this seems to be all there is—unless you know better. As for Mr Scorsese, the Telegraph had more of his foreword from the new monograph. And speaking of books, here’s another Bass link: Henri’s Walk to Paris, a children’s picture book that I wish someone had bought me in the 1960s.

Sea And Sky (1984) by Stomu Yamash’ta.

Blow Up (1991) by The Smithereens.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The album covers archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Pablo Ferro on YouTube

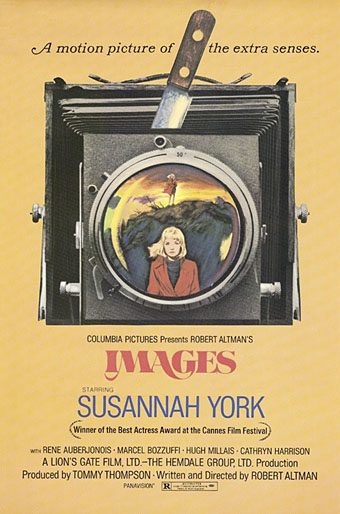

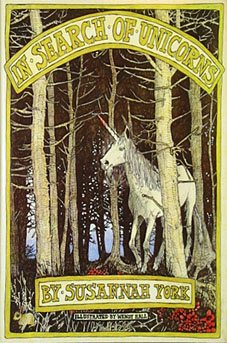

The screenplay for Images was all Altman’s work apart from Cathryn’s voiceovers where she reads (or writes in her head) parts of her novel. These were extracts from a real fantasy book for children, In Search of Unicorns, written by the actress, one of two she wrote in the 1970s. Those extracts add to the verisimilitude as well as being sufficiently naive and otherworldly to contrast with the very adult events being shown on the screen.

The screenplay for Images was all Altman’s work apart from Cathryn’s voiceovers where she reads (or writes in her head) parts of her novel. These were extracts from a real fantasy book for children, In Search of Unicorns, written by the actress, one of two she wrote in the 1970s. Those extracts add to the verisimilitude as well as being sufficiently naive and otherworldly to contrast with the very adult events being shown on the screen.