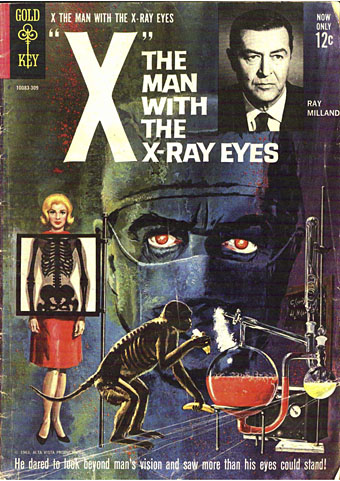

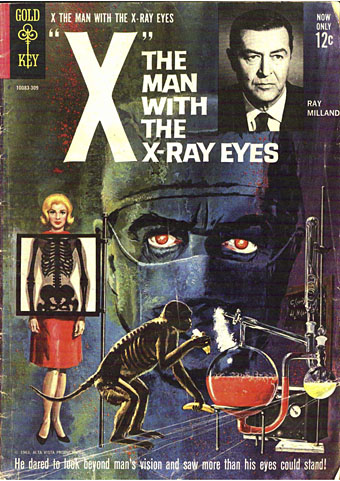

Cover art by George Wilson.

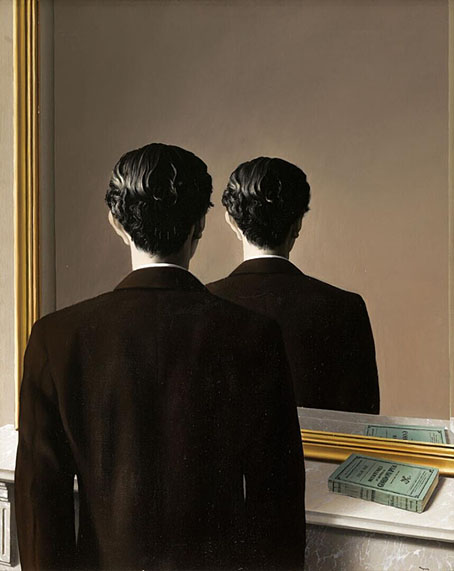

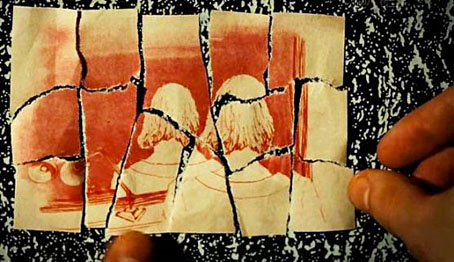

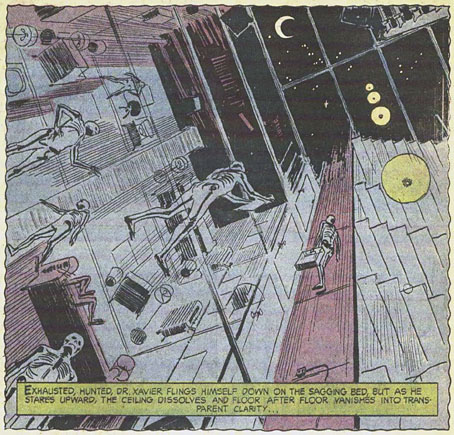

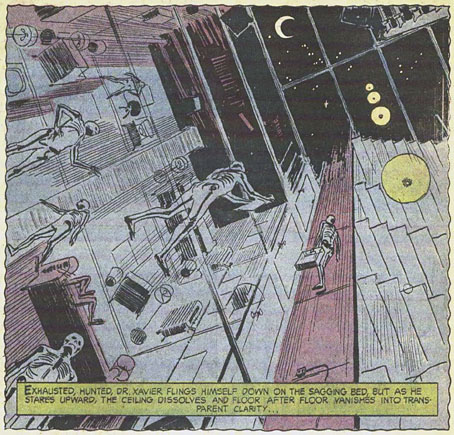

Cosmic weirdness isn’t something you expect to find in the tie-in comics published by Gold Key in the 1960s, but this adaptation of Roger Corman’s film contains a few such traces, as does the film itself. Having watched X: The Man with the X-ray Eyes again recently I was curious to know how artist Frank Thorne would manage with the scenes where Dr Xavier’s vision is showing him more of the world than he wants to see. Despite the general sketchiness of the drawing, in some of the panels these visions are more fully realised than they are in the film, it being easier to draw an unusual effect than capture it on celluloid. Roger Corman had a great idea, a talented co-writer in Ray Russell, and an authentically tormented performance from Ray Milland, but the film is hampered by the limitations of AIP’s budgets. When Xavier complains about the oppressive sight of people above him on the floors of his tenement building only the comic shows us what he sees.

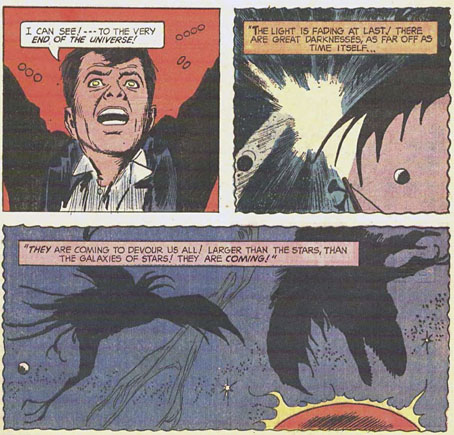

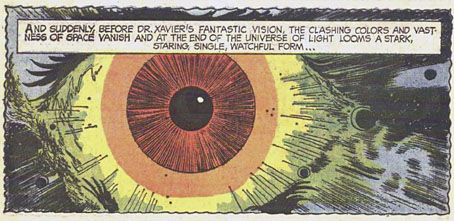

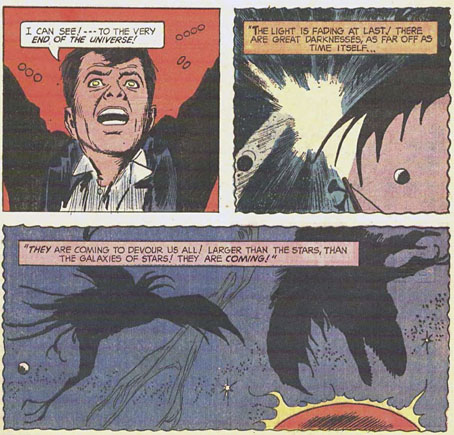

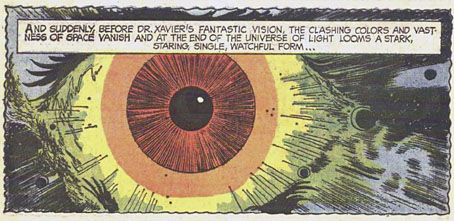

So too with the later scenes, by which time all of Corman’s point-of-view shots are the same combination of a diffracted lens (Spectarama!) and Les Baxter’s wailing theremin. Xavier’s description of a great watching eye “at the centre of the Universe” isn’t conjured so well by Corman’s visuals. The comic gives us an all-too-human eyeball floating in space, but before this there’s a panel of ragged shapes flapping through the interstellar void, as well as something never seen in the film when Xavier looks down into the Earth’s core.

The comic was written by Paul Newman (not that one), and was evidently adapted from a script rather than a print of the film. None of the characters or scenes resemble their cinematic equivalents, while Xavier’s eyes in the comic hardly change appearance. But the additions to the finale make me wonder whether there was a little more in the script than ended up in the film.

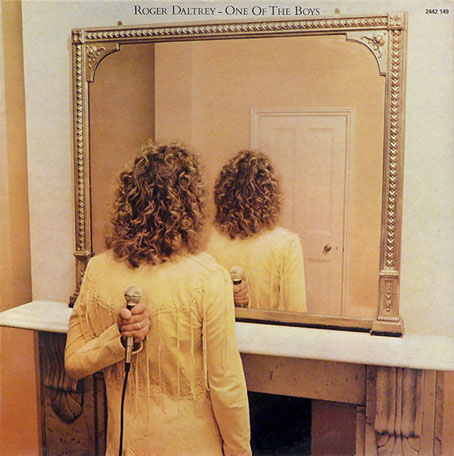

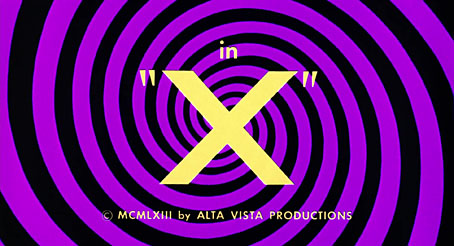

Corman made The Man with the X-ray Eyes in 1963, immediately after The Haunted Palace—the first film to adapt HP Lovecraft—and a few years before The Trip—the first feature film devoted solely to the psychedelic experience. Xavier’s journey into nightmare is a curious hybrid of Lovecraft and psychedelia: the titles are set against a swirling violet spiral, while the doctor’s Spectarama visions are precursors of the delirium experienced by Peter Fonda’s Paul in The Trip. (Corman’s initial idea for The Man with the X-ray Eyes had a jazz musician taking too many drugs.) At one stage in his LSD trip Paul looks in a mirror and announces that he can see inside his own brain, but in the earlier film we get to see inside Xavier’s brain for ourselves when he takes his eye drops for the first time, after which the camera passes through the back of the doctor’s head until we’re looking out of his eyes. This is so close to a moment in Gaspar Noé’s Enter the Void that I’ve been wondering whether Corman’s film is another of Noé’s cult titles like those you see named at the beginning of Climax.

As for the Lovecraftian quality, The Man with the X-ray Eyes misses an opportunity to do more with the scope of its central concept. Stephen King famously reported a rumour that the film had a suppressed line of dialogue from the very end, when Xavier tears out his eyes then screams “I can still see!” Corman denied that this was the case but admitted it was a good idea. King mentions this in Danse Macabre, in a description of the film which also interprets the story as being far more Lovecraftian—he uses that word—than it actually is. His suggestion (or mis-remembering) is that all the Spectarama effects are Xavier’s growing perception of the Eye at the centre of the Universe, even though Xavier only mentions this presence in the last few minutes.

The implications of this remain unexplored but Xavier’s final vision of cosmic horror is still truer to Lovecraft’s Mythos philosophy—a warning that the human race peers into the void at its peril—than almost anything else in cinema, and the revelation is made all the more disturbing by the appearance of Xavier’s eyes which by this point are solid black orbs. As King suggests, there’s another film altogether lurking under the surface of this one, a horror film with a cosmic reach. Hollywood still struggles to do anything substantial with Lovecraft’s fiction, but you know the way things are today we’ll be lucky to get anything weirder than more CGI monsters and lumbering kaiju. I wouldn’t want to suggest that Gaspar Noé remake The Man with the X-ray Eyes but if he ever wanted to create a psychedelic horror story then the cosmic route is the way to go.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Undead visions

• Trip texts revisited

• More trip texts

• Enter the Void