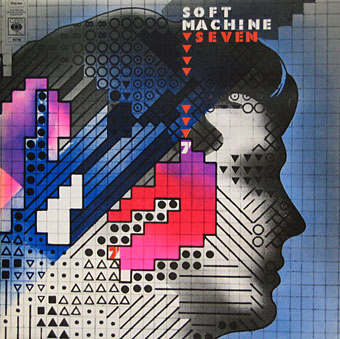

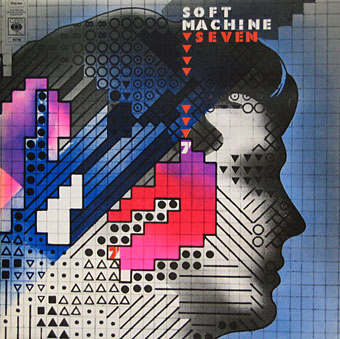

Seven (1973) by Soft Machine. Design by Roslav Szaybo.

You’re the great, grey man whose daughter licks policemen’s buttons clean,

You’re the man who squats behind the man who works the soft machine.

Mick Jagger, Memo From Turner (1968)

By coincidence this month I’d been re-reading some William Burroughs when I picked up a nice box set of five Soft Machine albums, part of a series of reissues that Sony have been doing recently. They’re very cheap and sound excellent, and also have the additional benefit of being a card slipcase holding the discs in card sleeves so there’s no nasty plastic packaging. The set comprises the Third (1970), Fourth (1971), Fifth (1972), Six (1973), and Seven (1973) albums. I have the band’s first two studio albums already so this has been an opportunity to get fully acquainted with the rest of their output up to the point where the machine started to run out of steam.

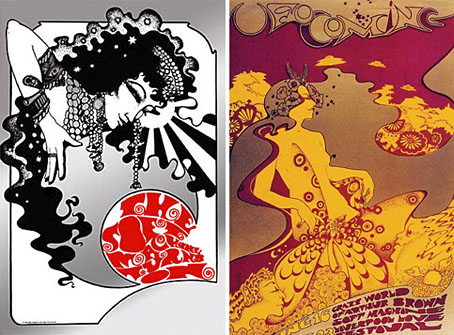

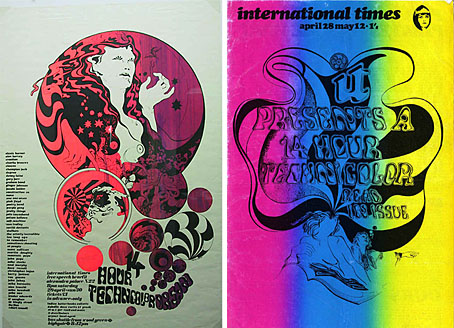

The Soft Machine (1968) with die-cut sleeve. Design by Byron Goto, Eli Allman, Henry Epstein.

Third and Fourth are freaked-out jazz fusion recorded when Robert Wyatt was still on drums; Fifth, which I had for years on vinyl, is post-Wyatt fusion of a more polite variety, great compositions but it sounds lightweight compared to Miles Davis’s On The Corner which was released the same year. Six, which I’d hardly heard at all, is a set of live recordings and four superb studio tracks. Seven is the weakest of the lot but it prompts this post on account of the cover which I always liked the look of when flicking past it in record shops. Seen today it still looks surprisingly advanced for 1973, and the intention behind the design is still mysterious. I used to regard it as vaguely “futuristic” despite knowing that the music was nothing of the sort. The accumulation of abstract symbols contained by a human head implies either a score for some aleatory composition (which again is belied by the short jazzy pieces within), or can perhaps be read as a “soft machine”, especially if one considers that the popular idea of electronics at this time involved patch-boards and banks of flashing lights. Ten years later with synthesizers in common use this kind of semi-cybernetic imagery was a lot more topical.

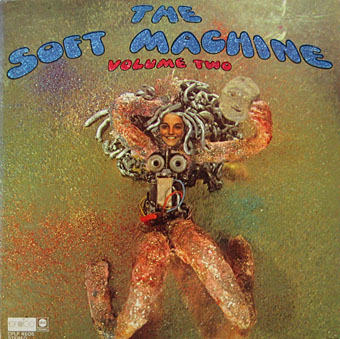

The Soft Machine Volume Two (1969). Design by Byron Goto, Henry Epstein.

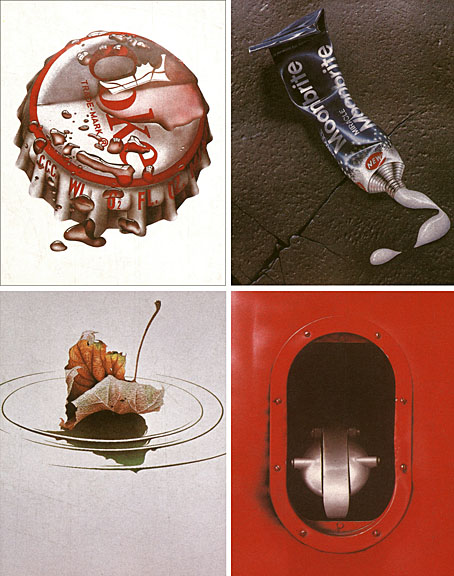

The first two Soft Machine albums both showed literal renderings of Burroughs’ “soft machine” idea albeit couched in the naked-woman-as-decoration style of the late 60s. Six has a horrible cover with an airbrushed attempt at a soft machine, one of those pictures common to the 1970s that you’re amazed was approved by band and record company.

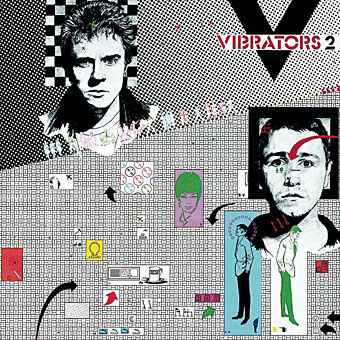

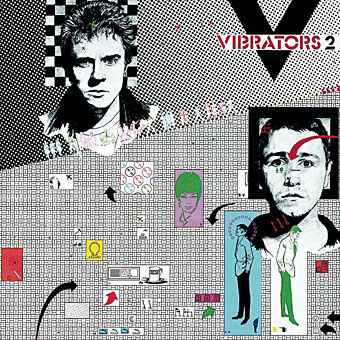

V2 by The Vibrators (1978). Design by Roslav Szaybo.

The design for Seven is credited to Roslav Szaybo, an in-house designer at CBS. Looking through Mr Szaybo’s other credits there’s little that resembles his Soft Machine cover until you arrive at the sleeve for V2, the second album by British punk band The Vibrators. This was another cover I always liked for similar graphical reasons to the Soft Machine sleeve; they also share a similar stencil typeface. Musically they’re worlds apart, of course, although William Burroughs’ influence on music carried on into the punk era (another Brit punk band named themselves Dead Fingers Talk) and beyond. It’s an influence reaching from the mid-60s with Soft Machine and his appearance on the cover of Sgt Pepper, into the 1990s with the many recordings he collaborated on or inspired from Bill Laswell, Hal Willner and others. His influence generally may have fallen off since his death in 1997 but it’s still a remarkable achievement for someone who never seemed to care much for music beyond the popular tunes he heard as a boy.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The album covers archive

• The William Burroughs archive