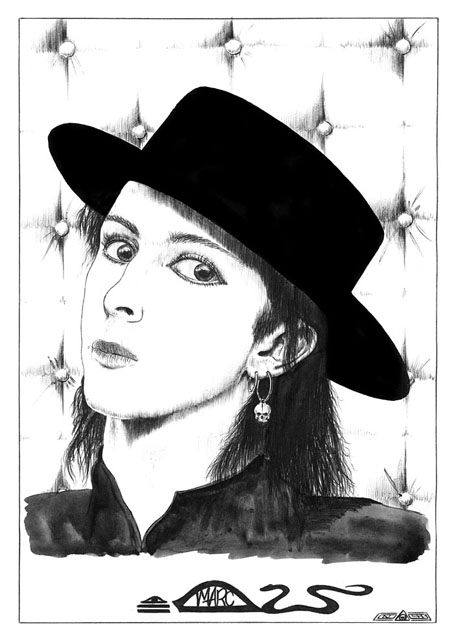

The Future Vol.2 (2016) by f1x-2.

• One of the notable things about the reaction to the original series of Twin Peaks was the way in which Americans were astonished that something so outré could be allowed on television. Here in the UK the response was a little more subdued; we had, after all been spoiled for years by The Prisoner, Sapphire and Steel, and numerous odd and challenging dramas by Dennis Potter and others. Pre-dating all of these was The Strange World of Gurney Slade (1960), a six-part series starring Anthony Newley that was unprecedented in its Surrealism. Andy Murray looks back at the series, and at the rest of Newley’s career.

• Andrew Dickson on Peter Ackroyd whose latest book, Queer City: Gay London from the Romans to the Present Day, is published later this month.

• Alyona Sokolnikova on a Soviet vision of the future: the legacy and influence of Tekhikia – Molodezhi (Technology for the Youth) magazine.

You know who weren’t cops? All the radicals and queers and artists and dreamers that were there while I grew up, my mom and dad’s old friends from New York and the wider bohemian world, the actors and the drag queens and the dilettantes and the ex junkies and the current junkies, the kind of queer people who wouldn’t get caught dead getting married, the people who actually made the “old New York” of the myth into what it was. They were smart and they were funny and they were tougher than I can imagine and they were possessed of an existential commitment to the idea that life is complicated and so we shouldn’t be quick to judge. They were tolerant, in the true sense, even while they were tireless advocates for actual justice. […] Now we’re Rudy Giuliani, trying to get offensive art pulled off the walls. Now we’re the book burners. Now we’re the censors. Now we attack the ACLU for defending free speech. Now we screech about community morals. Now we’re the prison camp screws. That’s us. Me, I could never be one of the good ones. Never. I can never live up to that ideal. I know I’m not good enough. I know when the judgment day comes, I go down. And so I decline. You can decline, too.

Planet of Cops by Freddie deBoer, or how inflexible morality makes everyone a cop

• Mixes of the week: FACT Mix 601 by Dark Entries, Secret Thirteen Mix 221 by Eli Keszler, and XLR8R Podcast 490 by Ben Lukas Boysen.

• At Dangerous Minds: Punk, Patti Smith, William Burroughs & capitalism: A “conceptual conversation” with RE/Search’s Vale.

• Emily Wells on the strange, irreverent worlds of Down Below and The Complete Stories of Leonora Carrington.

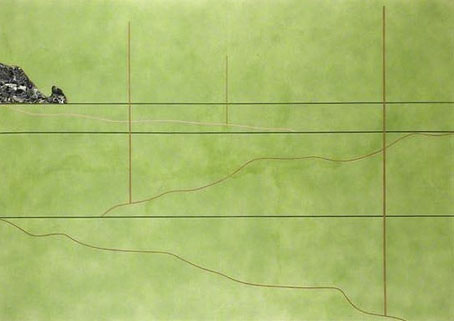

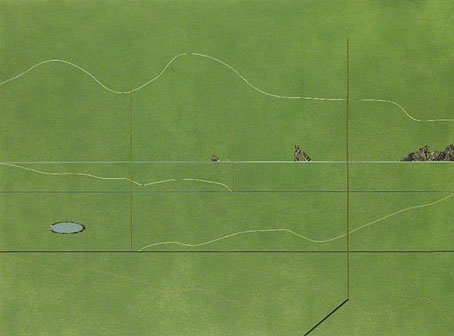

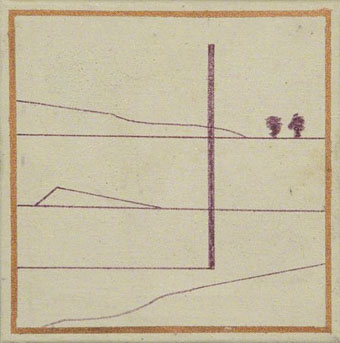

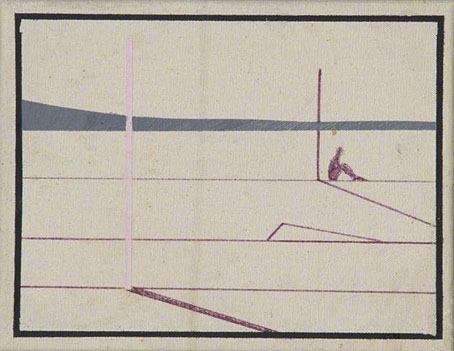

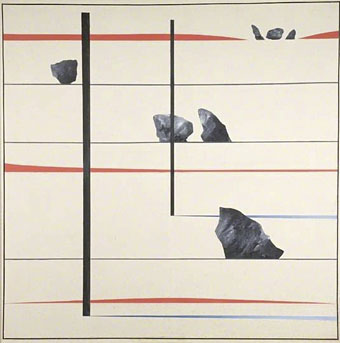

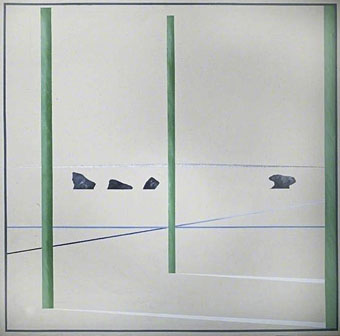

• Rick Poynor on Mike Halliwell’s montages based on JG Ballard’s The Atrocity Exhibition.

• “Why are the British so scared of cannabis?” asks Professor David Nutt.

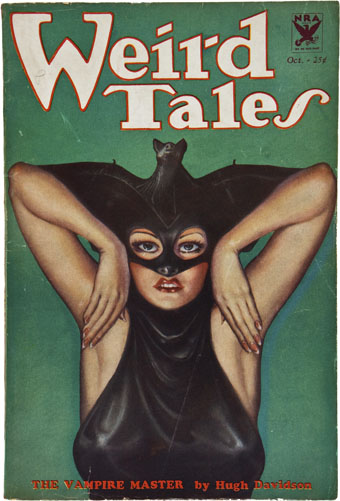

• Witchcraft and the Gay Counterculture (1978) by Arthur Evans.

• At Dennis Cooper’s: Jacques Rivette Day.

• Designing Penguin Modern Classics

• Future Dub (1994) by Mouse On Mars | Future Proof (2003) by Massive Attack | Future (2004) by Alva Noto