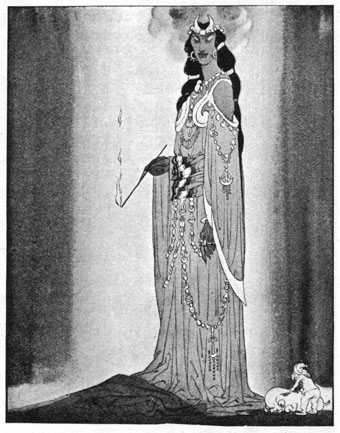

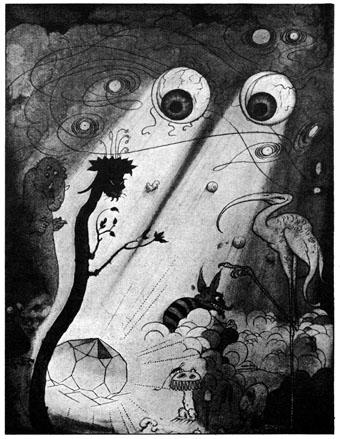

The Spirit of “Haschisch” by Sidney Sime.

Once upon a time, the discussion of drugs in British society wasn’t characterised by hysteria, paranoia and the repetition of falsehoods, but could encompass an open-minded curiosity. This is easier to do, of course, when the narcotics in question haven’t been subject to prohibition; it also helps if some of those narcotics have medicinal uses, as was frequently the case. The following article by HE Gowers, with illustrations by Sidney Sime, was published in The Strand Magazine for December 1905, a periodical famous for giving the world the adventures of the cocaine-using Sherlock Holmes. Also in issue 180 was an extract from Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sir Nigel (a turgid historical drama which the author bizarrely considered to be his masterpiece), The Adventure of the Snowing Globe by illustrator Warwick Goble, and Empire of the Ants, a chilling tale by HG Wells.

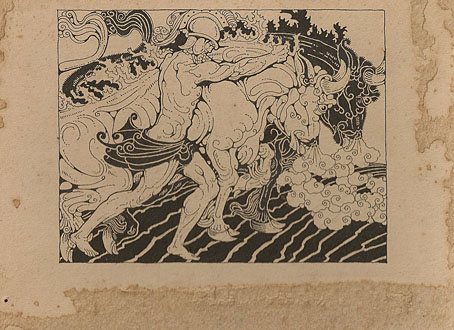

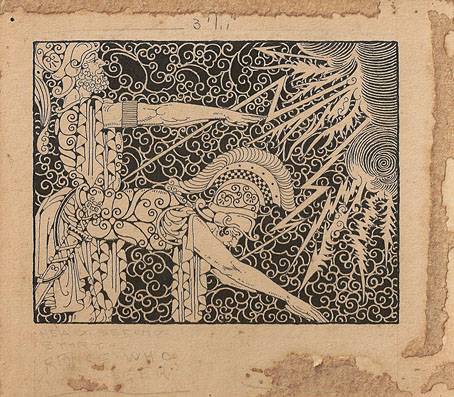

I was reminded of the Gowers piece earlier this week when Golden Age Comic Book Stories posted a selection of Sidney Sime’s Lord Dunsany illustrations. As well as working as a book illustrator, Sime was a regular contributor to magazines like Pall Mall and The Idler, and I’m fortunate to have a number of those otherwise unreprinted works in a scarce small-press collection which appeared in the 1970s. Sime’s illustrations here are taken from that volume which also included the partial text of the Gowers piece. With some searching around I was able to find the rest of the article and stitch the whole thing together. What’s nice about this essay is that the writing is for once as interesting as the illustrations; with Victorian and Edwardian magazines this isn’t always the case. Sime spent much of his life drawing unusual scenes but here he has a tough job to match the outré descriptions of what we’d have to class as episodes of Edwardian psychedelia. With the exception of Maurice Richardson’s Engelbrecht stories, this kind of outright weirdness wouldn’t be found in a British magazine for another sixty years.

* * *

HASCHISCH HALLUCINATIONS by HE Gowers

Illustrations by SH Sime

IN the eleventh century lived a fanatical Syrian sect who, under the intoxicating influence of haschisch, a native preparation of a plant called Indian hemp, committed many secret murders and fought recklessly against the Crusaders.

To-day many natives of Eastern lands fortify themselves with some form or the other—haschisch, bhang, gunjah, or churrus—of this drug. It has been repeatedly used in modern European medical practice, without, however, very consistent or satisfactory results.

A small dose of Indian hemp produces a feeling of cheerfulness and gives an increase of appetite; an overdose gives rise to strange errors of perception as to time and place, the patient’s heart-beats are much accelerated, intense thirst is generated, and often hallucinations of a most strange nature follow.

Mr. Bayard Taylor, in “Lands of the Saracen,” gives a graphic description of the effects produced on his travelling companion, Mr. Carter Harrison, and himself by a teaspoonful of paste made from a mixture of the dried leaves of cannabis indica (Indian hemp), sugar, and spices. About four hours after the haschisch was taken Mr. Harrison suddenly shrieked with laughter, and exclaimed excitedly:—

“Oh, ye gods! I am a locomotive!”

And then for over two hours he continued to pace to and fro the room in measured strides, exhaling his breath in violent jets, and when he spoke dividing his words into syllables, each of which he brought out with a jerk, at the same time turning his hands at his sides, as if they were the cranks of imaginary wheels.

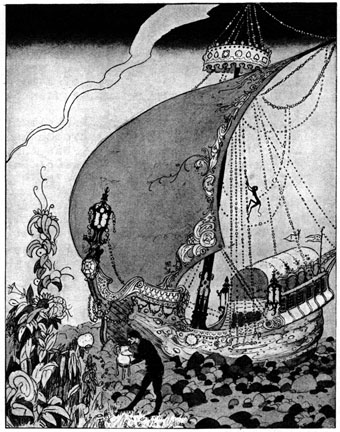

“He was moving over the desert in a barque of mother-of-pearl.

Mr Taylor’s hallucination was of a far more varied nature. He fancied himself at the foot of the pyramid of Cheops. He wished to ascend it, and was immediately at the top. Looking down, it seemed to be built out of plugs of Cavendish tobacco. Then other and stranger illusions followed. He was moving over the desert in a barque of mother-of-pearl, studded with jewels of surpassing size and lustre, and soon reached a waterless land of green and flowery lawns, where honey was drawn up in dripping pitchers. Later, when the drug began to make itself more powerfully felt, the visions were more grotesque and of less agreeable nature. His body seemed twisted into various shapes, and yet he had to laugh; his mouth and throat were as dry as if made of brass; his tongue seemed a bar of rusty iron. The excited blood rushed through his frame with a sound like the roaring of mighty waters; it was projected into his eyes so that he could not see, and beat thickly in his ears. His heart seemed bursting. He tore open his vest and tried to count the pulsations; but there were two hearts beating, one at the rate of one thousand beats per minute, the other with a slow, dull motion. Finally, he slept for thirty hours.

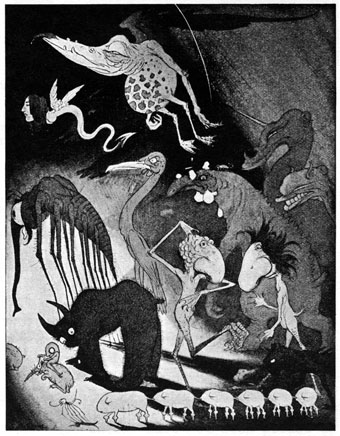

“All the menageries of monstrous dreams, trotted, jumped, flew or glided through the room.”

Another great traveller in the East, according to Théophile Gautier, says that after a large dose of haschisch, two images of each object were reflected on each retina and produced a perfect symmetry. Then all kinds of Pantagruelic dreams passed through his fancy. Goatsuckers, storks, striped geese, unicorns, griffins, nightmares, all the menageries of monstrous dreams, trotted, jumped, flew or glided through the room. He saw horns terminating in foliage; webbed hands; whimsical beings, with the feet of his armchair for legs and dial-plates for eyeballs; enormous noses, dancing the cachuca while mounted on chicken legs. He imagined he was the parakeet of the Queen of Sheba, and imitated, to the best of his ability, the voice and cries of that bird. Then, with inconceivable rapidity he sketched these gruesome creatures on the backs of letters, cards or any handy piece of paper. He found, when the effects of the drug were past, that one of his frantically-drawn sketches bore the inscription: “An animal of the Future.” It represented a living locomotive with a swan’s neck terminating in the jaws of a serpent, whence issued jets of smoke, with two monstrous jaws composed of wheels and pulleys; each pair of jaws had a pair of wings, and on the tail of this fearsome creature was seated the Mercury of the ancients.

“Take care; you’re spilling me!” emphatically exclaimed another experimenter, Mr. S.A. Jones, a few hours after taking ten grains of haschisch.

“What’s the matter, old man?” asked the friend who was with him in his bedroom.

“Stupid, you’ll spill me! Can’t you see I’m an inkstand, and that you’ll have the ink all over the white counterpane?”

And for an hour, in the person of an inkstand, he opened and shut his brass cover—it had a hinge—shook himself, and both saw and felt the ink splash against his glass sides.

One of the most common effects of haschisch, previously mentioned, is to make everything appear a great way off, and a few seconds seem so many hours, or even weeks. Among the many strange illusions experienced by Mr. Shirley Hibbard, these distorted ideas of time and distance play a prominent part. He says that his room became larger and larger, and the skulls of animals that ornamented his study walls became colossal, and seemed monsters of the oolitic age. He seemed to have been staring at them for years, but after looking at his watch and finding that he had been under the influence of the drug but twenty minutes, the illusion was temporarily dispelled… Then suddenly the watch began to expand, and ticked like the pulsations of a world. He seized a pencil with the intention of taking notes, but his limbs became convulsed, his toes shrank within his slippers, his fingers became the long legs of a convulsed spider, and the pencil dropped with a thunder-like crash. He looked out of the window and beheld a sublime spectacle. The horizon was infinitely removed; the sunset had marked it out with myriads of fiery circles, revolving, mingling together, expanding, and then changing into an aurora which shot up into the zenith and fell down in sparks and splashes among some trees, which became brilliantly illuminated. The landscape continued to expand. The trees shot higher and higher until their mingled branches o’erspread the gradually-darkening sky. With a mighty effort of will, he managed to look at the watch again, and discovered that only twenty-five minutes had passed.

He screamed: “Twenty-five minutes, twenty-five days, twenty-five months, twenty-five years, twenty-five centuries, twenty-five aeons. Now I know it all. I have discovered the elixir of life; I shall live for ever.”

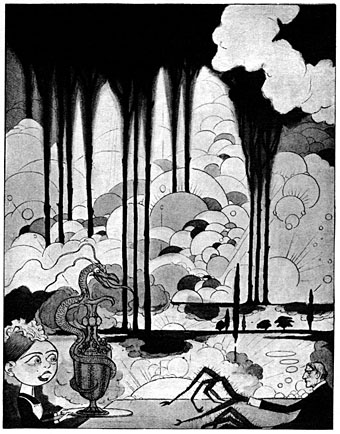

“The cup seemed a huge tankard, beautifully chased all over with dragons.”

As his heart was beating very fast he tried to count his pulse. The throbs were like the heaving of mountains; as he counted “One, two, three,” they became “One, two, three centuries,” and he shrieked at the thought of having lived from all eternity and of going to live to all eternity in a palace of coloured stalactites, supported by shafts of emerald resting on a sea of gold… A servant brought him a cup of coffee. He says the cup seemed a huge tankard, beautifully chased all over with dragons that extended all round the world. The girl appeared to stand for an hour smiling and hesitating where to place the cup, as the table was strewn with papers. He then removed a few papers, and heaved a sigh that dissipated the dragons and made odours fall in showers of rain; the servant put down the cup with a crash that made every bone in his body vibrate as if struck by ten thousand hammers. The maid stood aghast, and her rosy face expanded to the size of a balloon, and away she went like lightning while he stood applauding in the midst of thousands of fairy lamps, which he noticed were glow-worms. He drank the coffee, which caused sensations of insupportable heat, and found that forty minutes had gone by since he took the haschisch. He then went to bed—a difficult undertaking, as his legs seemed so very long. On undressing, his clothes flew away into space. As he got into bed it extended, and his body covered the whole earth. Then followed a sense of indescribable pain all over his body; his skin seemed to move to and fro upon his flesh, his head swelled to an awful size, and, finally, his body parted in two from head to foot… Unlike most persons Mr. Hibberd felt in his usual good health the next morning.

“He distinctly saw within himself the drug he had chewed.”

As will have been noticed from the last experience the intoxicating effect of haschisch is not continual; but, like madness, has its short lucid intervals. The doctor whose sensations are described below says that his attack was easily divisible into three stages, each increasing in strength and weirdness, and that there was a brief period of comparative sanity between each.

He distinctly saw within himself the drug he had chewed: it looked like an emerald, from which thousands of sparks were emitted. His eyelashes grew rapidly, and when about two feet long twisted themselves like golden threads around little ivory wheels, which whirled rapidly. Half animals and half plants his friends appeared; and a pensive ibis standing on one leg addressed a discourse on music in Italian, which the haschisch delivered in Spanish. Later, after a clear interval, his hearing was wonderfully developed. He could hear the sound of colour—green, red, blue, and yellow sounds struck his ear with perfect distinctness. For fear of razing the walls and bursting like a bomb he dared not speak. More than five hundred clocks (in reality, one) chimed the hour. He swam in an ocean of sound, wherein beautiful passages from the operas floated like islets of light. He felt as a sponge in the midst of the sea; every instant waves of happiness washed over him, entering and departing through his pores, for he had become permeable, and even to the smallest capillary vessel his whole being was filled with the colour of the fantastic medium in which he was plunged… According to his calculations this stage must have lasted three hundred years, for the sensations succeeded each other so rapidly and potently that the real appreciation of time was impossible. When the attack was over he found that it had lasted just a quarter of an hour! •

The Strand Magazine, 1905.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The illustrators archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Demon rum leads to heroin

• Sidney Sime and Lord Dunsany

• HP Lovecraft’s favourite artists

• German opium smokers, 1900