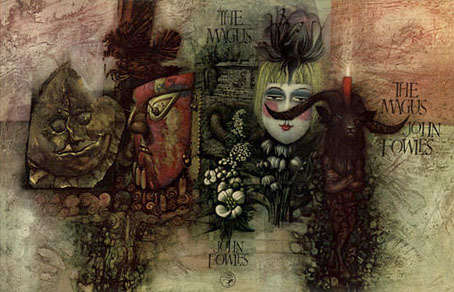

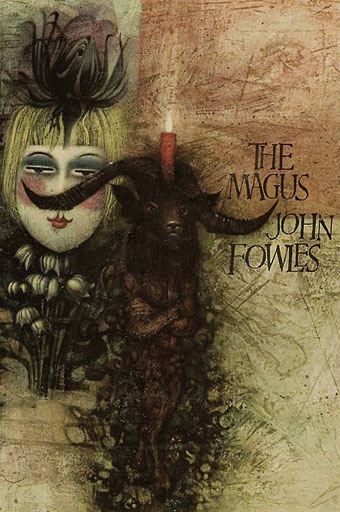

Dust jacket for The Magus (1966) by John Fowles.

I pulled my 1982 paperback of John Fowles’ The Magus from the bookshelf recently. After flicking through the pages I decided to start re-reading it, having realised that in the thirty years which have elapsed since I first read it I couldn’t remember much at all about it. One thing I did remember, however, was the cover of the first edition, a painting and design I’d admired in the past without knowing the name of the artist responsible.

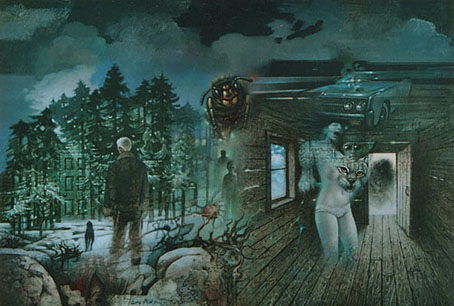

American illustrator Tom Adams is the artist in question, and looking at his painting again it further occurred to me that his cover deployed an evocative but not wholly specific assemblage of figures and objects that I’d often seen elsewhere, notably on the first edition cover of Peter Straub’s Ghost Story. So it was no great surprise to discover that Tom Adams was also responsible for that cover painting. The Fowles and Straub novels are big books which slowly reveal their layered mysteries. Adams’ approach to illustrating them strikes me as an ideal solution when neither of the novels can be easily reduced to a single image. (This hasn’t prevented subsequent designers from trying.) Fowles approved wholeheartedly of the painting but this isn’t a particularly fashionable technique at the moment, the trend being to try and condense complex narratives into a single motif.

Cover painting for Ghost Story (1979) by Peter Straub.

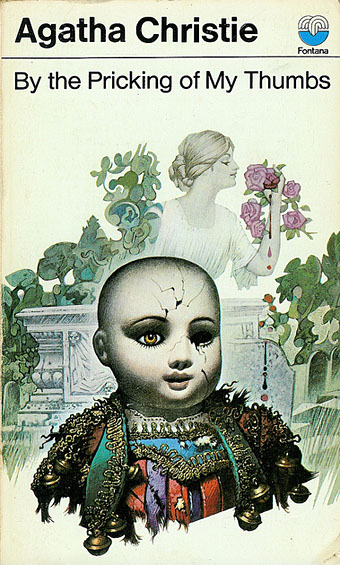

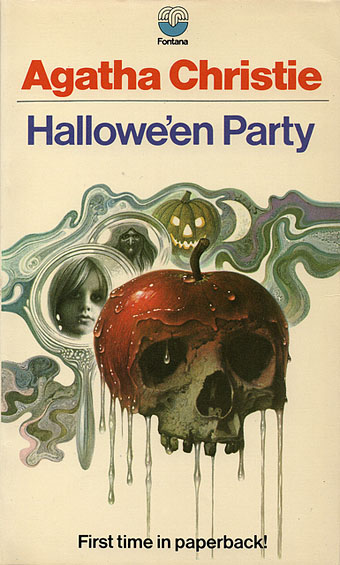

Looking for more of Adams’ art tipped me into an entire world of Agatha Christie book covers which were the artist’s main body of work for many years. Adams is understandably celebrated by Christie-philes (Paper Tiger published a book of his Christie covers in 1981) but outside Sherlock Holmes and Father Brown I’ve never had much of a taste for the classic detective story so this was a previously undiscovered niche. Here Adams sidesteps the chore of painting Christie’s meddlesome sleuths in favour of a remarkable display of grotesque Surrealism which—for a sceptic such as myself—makes the books seem potentially interesting. As with The Magus and Ghost Story there’s the same assemblage of evocative figures or objects but with an additional macabre twist. Many of these covers are so grotesque they could easily function as horror illustrations so it’s no wonder he was asked to illustrate the Straub. This Flickr page has many more examples (warning: wretched user-unfriendly Flickr layout in operation) as does this site. The artist has a website where prints of The Magus painting may be purchased.