The Dance of Salomé (1885) by Robert Fowler.

There’s always more to find… Unfortunately, Robert Fowler’s academic tableaux is a prime example of bad Victorian art: carefully modelled but overlit, dull and lifeless. And worst of all for the subject at hand: deeply unerotic. We’re supposed to believe that this woman wrapped in a bedsheet would exude enough eros to drive her father to lustful recklessness. This was the bloodless “good taste” against which Oscar Wilde and the Aesthetes set themselves.

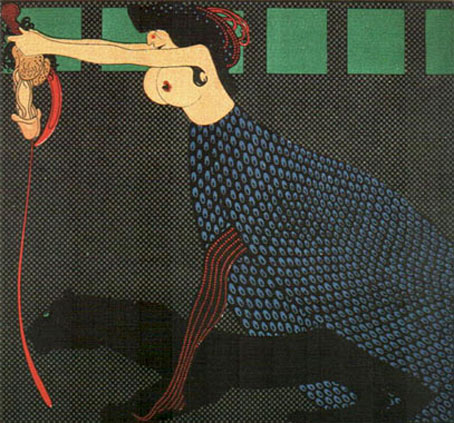

Salomé Dancing before Herod (1876) by Gustave Moreau.

Wilde’s idea of Salomé can be seen here in one of Gustave Moreau‘s many paintings on the theme. Wilde would have preferred Moreau’s paintings, or something similar, to adorn his published play but he ended up with Aubrey Beardsley instead. You only have to compare Beardsley’s Stomach Dance with Fowler’s painting to see why Aubrey’s art made such a dramatic impression in the 1890s.

Salomé (1890) by Ella Ferris Pell.

Ella Ferris Pell’s painting isn’t the only portrait of Salomé by a female artist of this period but it’s the one which Bram Dijkstra chose as the cover image for his excellent study Idols of Perversity: Fantasies of Feminine Evil in Fin-de-Siècle Culture (1986). Of this work Dijkstra writes:

In Pell’s painting a number of the most characteristic turn-of-the-century attributes of the biblical temptress are absent. She does not glare at us with a look of crazed sexual hunger; she does not have the wan, vampire features of the serpentine dancer; nor does she show herself to be a tubercular adolescent … Pell’s Salomé, a real life-woman, independent, confident, and assertive, was far more threatening, far more a visual declaration of defiance against the canons of male dominance than any of the celebrated viragoes and vampires created by turn-of-the-century intellectuals could ever have been. Such a woman could not be disposed of in as cavalier a fashion as the evil women in man’s mind. Her indomitable reality was this feminist Salomé’s most formidable weapon, far more dangerous than any imaginary decapitating sword.

Salomé (1909), two paintings by Robert Henri.

Finally, there’s this pair of paintings by American artist Robert Henri whose work resembles John Singer Sargent’s in its shadowed backgrounds and light brushstrokes. Salomé was no longer a perennial theme by this point but Maud Allan’s improvised dance performance, Vision of Salomé, was proving enormously popular at the time Henri painted these pictures which may explain his choice of subject. There’s little in the rest of his oeuvre along similar lines.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The Salomé archive