Atalanta and Hippomenes (c. 1612).

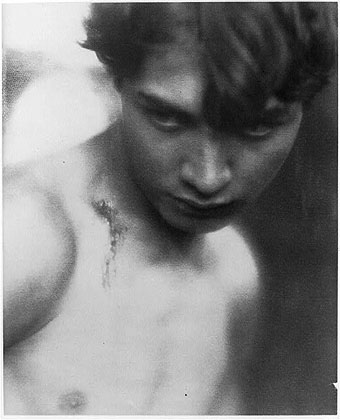

More golden apples appear in this painting by Guido Reni, not the most famous ones in art history—those would be all the Apples of Discord seen in the various Judgements of Paris—these are the fruit of the sacred tree in the Garden of the Hesperides which Hippomenes drops to prevent Atalanta from beating him in a race. The object of interest here isn’t the apples but the near-naked male, a favourite subject for Baroque artist Guido Reni whose work strikes viewers today as significantly homoerotic. This interpretation is by no means a recent one: Oscar Wilde was famously smitten with Reni’s depiction of Saint Sebastian (below) when he saw the painting in Genoa; in the 20th century the same painting (or one of Reni’s other Sebastians) excited the 12-year-old protagonist in Yukio Mishima’s novel Confessions of a Mask. Here’s what GLBTQ has to say about Reni:

Given the fierce homophobia prevailing in Europe during the Baroque era, historians seeking to reconstruct the lifestyles and works of queer artists often have to depend upon undocumented anecdotes and innuendoes.

Utilizing this type of evidence (including rumors about his supposed disdain of women, his possible romantic involvement with his long-time assistant, his interest in cross-dressing, and his “delicate” mannerisms), recent scholars interpret Guido Reni (1575–1642) as a gay artist.

The disdain of women is referred to in an earlier account, as are other pertinent details:

He was accustomed to paint with his mantle about him, gathered gracefully over his left arm. His pupils, of whom he had a great number—at one period no less than eighty, drawn from nearly every nation of Europe—vied with each other to serve him, esteeming themselves fortunate to have opportunities to clean his brushes or to prepare his palette. He had no dearth of models in the multitude of youths and disciples which surrounded him; but all that Guido cared of them was to refresh his memory by viewing their limbs and torsos, and after that he could adjust them and correct their imperfections.

In the same way any head sufficed him for a model. Being once besought by Count Aldovrandi to confide in him who the lady was of whom he availed himself in drawing his beautiful Madonnas and Magdalens, he made his color-grinder, a fellow of scoundrelly visage, sit down, and commanding him to look upward, drew from him such a marvelous head of a saint that it seemed as if it had been done by magic. Better than any other artist he understood how to portray upturned faces, and boasted that he knew a hundred ways of making heads with their eyes lifted to heaven. He often declared that his favorite, models were the ‘Venus of Medici’ and the wonderful heads in the Niobe group.

He was always in great fear of sorcery and poisoning, and for that reason could not endure women in his house, abhorring to have any dealings with them, and, when such were unavoidable, hurrying them through as rapidly as possible. Old women were his especial detestation, and he always fled from them, and lamented grievously if one of them should appear when he was about beginning or closing some commission.

From Guido Reni (1903)

That’s one way of either justifying your misogyny or explaining to the neighbours why your house is full of young men with no women.

Saint Sebastian (1615).

Speculation about the sexuality of artists from past centuries seldom leads anywhere but it can be a fun parlour game, provided you take accounts like the one above with a pinch of salt. In Reni’s case you’d have to point to the many paintings where a religious subject is used as the merest pretext for some shirtless male pulchritude. This was a common ploy in other areas of art: landscape painting evolved as a genre in its own right when post-Renaissance artists began to shrink the religious figures who were the ostensible subject of their commissions into the corner of a field or the shadows of a valley; the imagination could be given free rein by the expedient of painting an apocalypse or a Temptation of St Anthony.

Reni lets loose his temperament by returning to a range of religious subjects that happen to feature attractive youths. Even his picture of Sacred Love defeating Profane Love (below) shows a divine figure who seems to represent more of the libido than the subject should require. Elsewhere he follows Caravaggio with a youthful John the Baptist preaching in the wilderness in an almost total state of nature. Reni’s angels are some of the most androgynous figures you’ll find in Baroque painting; the model for his very girlish Archangel Gabriel also appears as Jesus in another painting, raising a somewhat scandalous implication as to the real paternity of Christ.

David with the Head of Goliath (1605).

The following selection of paintings is a prejudiced choice, of course. Some of these can be seen at a much larger size at the Google Art Project. Frivolous speculation aside, at his best Reni could be very good indeed as in this superb portrait of Saint Matthew with another androgynous angel. It’s no surprise to read that his work was in great demand throughout his life.

Continue reading “The art of Guido Reni, 1575–1642”