In the days before our present age of cultural plenitude, recordings by Greek composer Iannis Xenakis weren’t always easy to find. My haphazard introduction to contemporary composition came via record libraries and secondhand shops but even in these havens of obscurity discs of Xenakis music remained frustratingly elusive. Today I do own a few Xenakis CDs but there’s still a large portion of his work that I’ve yet to hear. After watching Mark Kidel’s documentary I’m persuaded once again that the gaps in my listening ought to be filled.

20th-century composition can be intimidating to the unitiated. Intimidating to listen to when so much of it is about finding new sounds, new structures, new modes of performance; and intimidating to read about when the discussion involves the analysis of very cerebral or technical conceptions. It can also disappoint when the results of those conceptions fail to hold the attention or excite the emotions. Many Xenakis compositions had their origin in mathematics or scientific theory but the musical results are consistently powerful and dramatic, even unnerving in a manner familiar from the works of Penderecki and Scelsi.

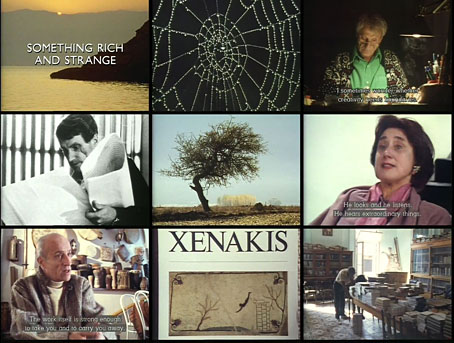

Mark Kidel’s hour-long documentary gives a small taste of the musical power and drama, especially in Roger Woodward’s performance of Eonta, a short composition for solo piano that’s astonishing to hear and see. Something Rich and Strange was made for the BBC in 1990 but it’s one I missed on its original broadcast so it’s good to find in a quality copy on the director’s Vimeo pages. The note there describes the film as a definitive portrait which sounds like a boast but there aren’t many Xenakis documentaries to choose from and it is very good, if a little too short for its subject. The film follows the composer and his wife, Françoise, as they journey to the Greek island of Spetsai where Xenakis spent several years at school in the 1930s. His reminiscences (or refusal of them) are interwoven with a sketch of his remarkable life which in its early years involved fighting with the Greek Resistance during the Second World War (and losing the sight in one eye as a result), fleeing to Paris in the post-war period after being condemned to death in absentia by the authoritarian Greek government, and working as an architect with Le Corbusier in the 1950s before deciding to devote the rest of his life to music. Kidel’s views of the Greek landscape wordlessly demonstrate the parallels between Xenakis’s music and the sounds of that landscape—goat bells, water lapping in a cave, a priest hammering a piece of wood—but we don’t hear much discussion of the composer’s musical evolution. His interest in electronic music, for example, is briefly mentioned but dismissed as being a direction he was unwilling to follow. But it was a direction he followed intermittently for at least a decade, and his electronic compositions would occupy several hours of your time if listened to in sequence. That’s the problem with trying to sum up a diverse career within the bite-sized limits of broadcast media; if the film was longer there would have been more time to address both the life and the details of the work. As it is, this is still an excellent introduction to a great composer.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Vasarely, a film by Peter Kassovitz

• A playlist for Halloween: Orchestral and electro-acoustic