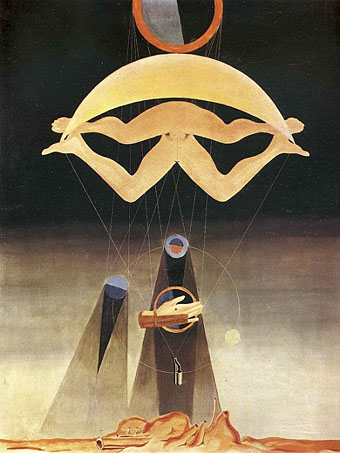

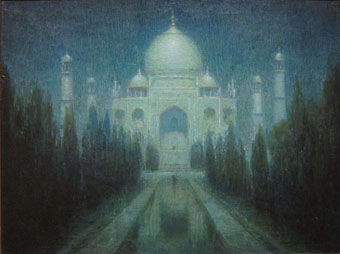

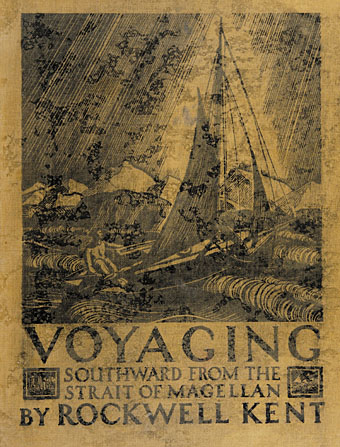

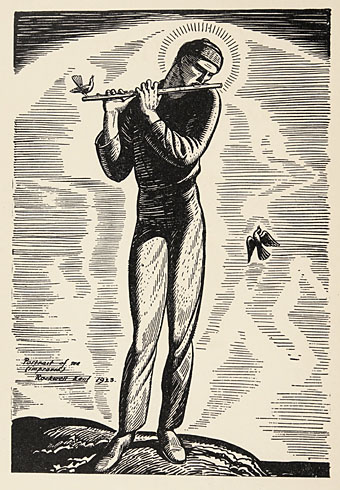

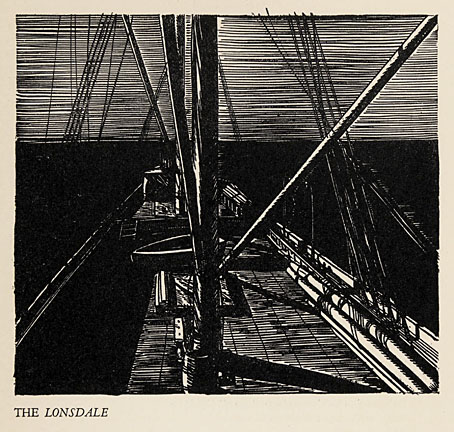

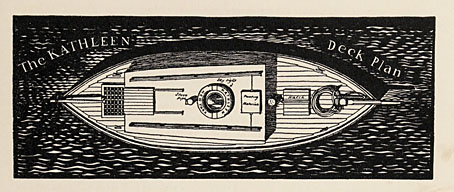

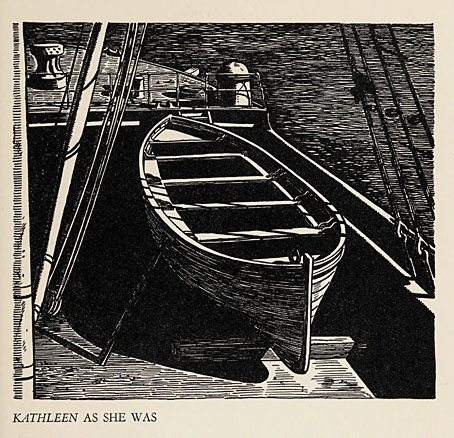

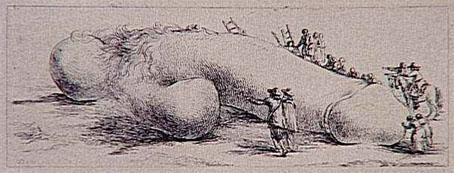

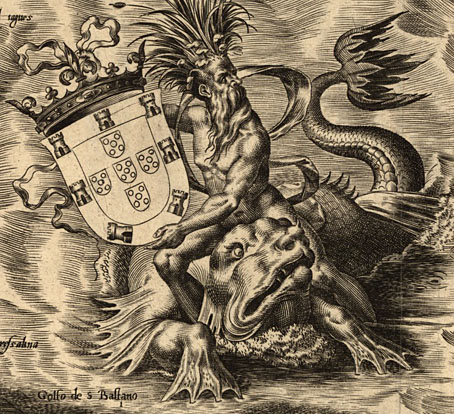

Wilderness: A Journal of Quiet Adventure in Alaska (1920) was Rockwell Kent’s first book, an illustrated memoir written by Kent and his wife, Frances Lee, which recounts several months the couple spent with their son on Fox Island in Resurrection Bay, Alaska. Most artists would illustrate something like this with drawings intended to evoke the remote location and its wildlife, and Kent does provide a number of documentary vignettes. Many of the full-page drawings are very different, however, being Blake-like renderings of nude figures representing a variety of moods and conditions. There’s a lot of this mysticism in Kent’s work, it’s what makes his art stand apart from the jobbing illustrators who were his contemporaries. You could also argue that Kent’s mystical nature and his love of voyaging to remote places, whether on land or sea, is why his Moby Dick from 1930 is the definitive illustrated edition. Don’t take my word for it, see for yourself.