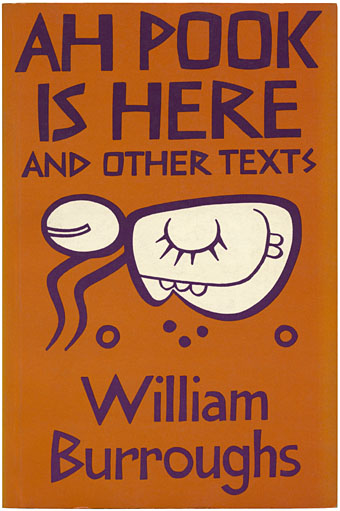

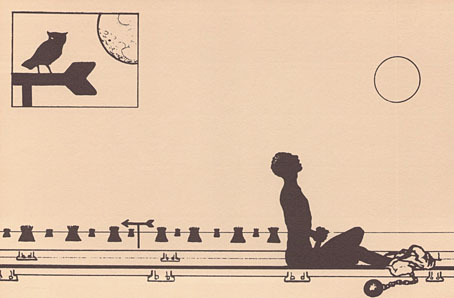

John Calder edition (1979). Design by Brian Paine incorporating a glyph of Ah Pook from the Dresden Codex.

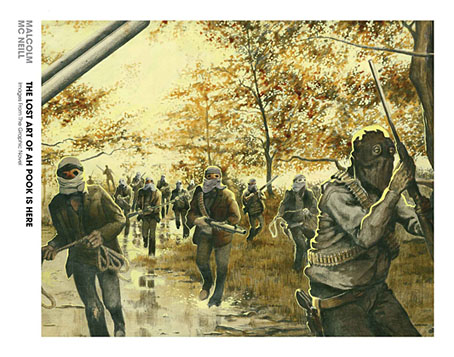

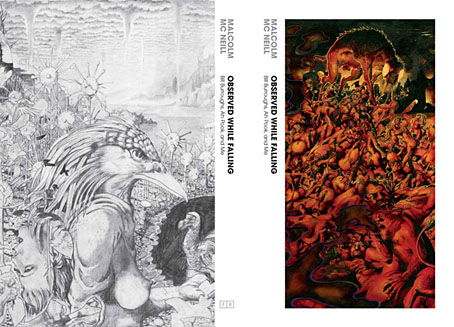

It would have been tempting to write “Ah Pook is finally here” but that’s not quite the case. Artist Malcolm McNeill sent Savoy Books the following preview images last week. What was originally going to be the long-awaited publication of McNeill’s collaboration with William Burroughs, Ah Pook Is Here, will now be two separate volumes published by Fantagraphics Books later this year: The Lost Art of Ah Pook Is Here which will comprise McNeill’s art without the accompanying text (apparently the Burroughs estate objected to its inclusion), and Observed While Falling—Burroughs, Ah Pook and Me, a memoir of the project’s creation. The loss of the text is an annoyance but not the end of the world, at least if you’re fortunate enough to own the scarce Calder book above which comprises a 40-page story that I imagine (and hope) may be read whilst viewing McNeill’s meticulous artwork. Amazon’s listing shows the two books scheduled for October 2012, and there’s now a website for the two books with further preview images.

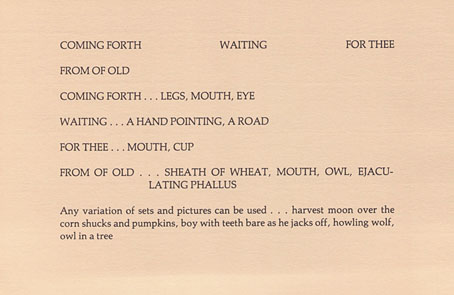

The 1979 Ah Pook Is Here is a fascinating collection, not least for the title piece which fits with the Wild Boys/Port of Saints narratives that Burroughs worked on during the 1970s. It’s also one of the better Burroughs anthologies so it’s always seemed odd that it’s remained resolutely out of print. Burroughs mentions McNeill’s artwork in a preface but doesn’t show any examples of his work. There is other artwork, however: in addition to some uncredited line drawings of figures like those in the Mayan codices there’s the whole of The Book of Breeething, a collaboration with artist Robert F. Gale from 1974. The latter concerns Burroughs’ interest in hieroglyphic communication, and attempts to show how one might convey short sentences through visual images alone, as in the pages below.

The Book of Breeething (1974).

The final piece in the book is The Electronic Revolution, an essay about using technology for guerilla purposes which was an inspiration for Cabaret Voltaire and others. All of this is choice and unusual material so it’s surprising that it’s been out of print for so long. In the case of Ah Pook Is Here it’s even more surprising to find it being prevented from republication despite Burroughs’ hope in his 1978 preface that the text would eventually be published along with the artwork. I’m sure the Burroughs estate have their own reasons for these manoeuvres but you can’t help but feel that this is another example of best intentions acting posthumously against the wishes of the artist they represent. A final irony can be found on the first page of Ah Pook Is Here where we see several mentions of a predatory agency that Burroughs warned against throughout his career, the thing he called CONTROL.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The William Burroughs archive