“Such stuff as dreams are made on”: Heathcote Williams and Toyah Willcox.

DVD viewing earlier this week was Derek Jarman’s wonderful adaptation of The Tempest which he directed in 1979. This is my favourite of Jarman’s films, partly because the play is my favourite Shakespeare (along with its polar opposite, Macbeth) and also because it’s a film infused with an occult sensibility which comes directly from the director’s own interests, rather than being the usual film or theatre conventions of what magic entails. An example of this is the grimoire which Prospero (Heathcote Williams) is seen leafing through which Jarman reveals in his autobiography, Dancing Ledge, to be his own 17th-century edition of Cornelius Agrippa’s Occult Philosophy. In his account of the filming he also describes his conception of Prospero as being based on Dr John Dee, the Elizabethan occultist who Shakespeare would certainly have known of, and may even have met since the pair both had business with Elizabeth I’s court. The most explicit reference to Dee comes in the shape of Prospero’s magical glass (above), based on Dee’s Monas Hieroglyphica, and a prop I’d dearly love to own. Dee was also a character in Jarman’s Jubilee (1978), and his Angelic Conversations gave a title to Jarman’s later filming of Shakespeare’s sonnets.

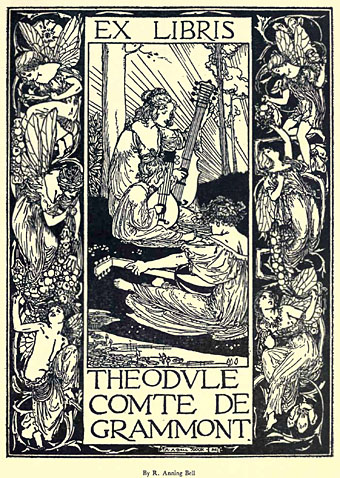

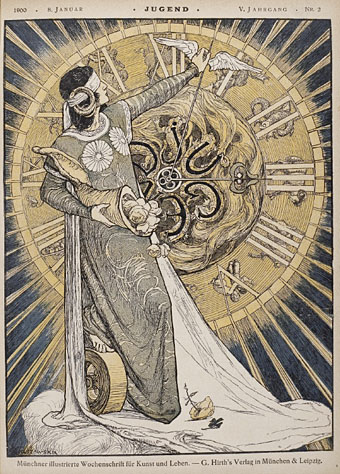

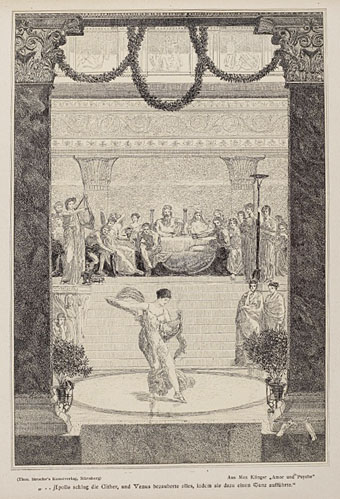

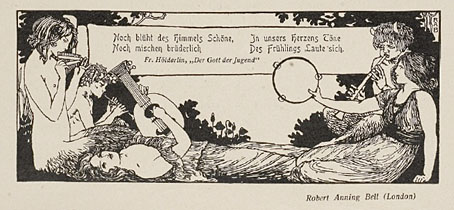

Seeing Jarman’s adaptation again had me thinking about the various representations of the characters. Ariel is generally depicted as a fairy type although he’s a lot more powerful than the fairies in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. As for Caliban, like Grendel in Beowulf, he’s an all-purpose monster whose predominant attributes seem to be whatever Ariel isn’t: ugly, earthbound, stupid, treacherous, and so on. I’d be tempted to propose the island’s quartet as representing the four elements—Prospero: water; Miranda: fire; Caliban: earth; Ariel: air—but I’m sure that’s not an original idea given the amount of academic trawling through the Bard’s corpus. Rather than dig for symbolism, what follows is a few pictures found during another trawl of my own through the Internet Archive, where the books aren’t drowned but patiently await their rediscovery.

Continue reading “The Tempest illustrated”