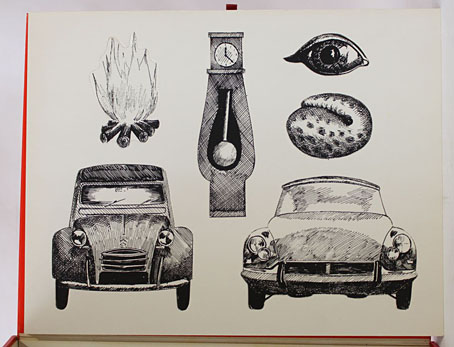

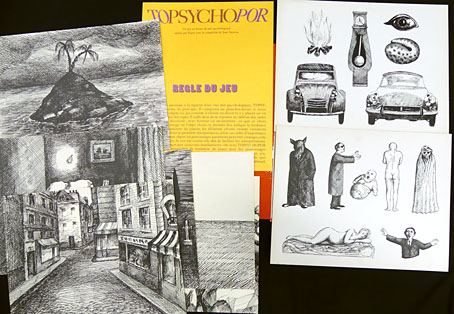

Published in Paris in 1964, “a game in the form of a psychological test produced by Topor with the help of Jean Suyeux”. A red box measuring 41 x 32 cm, containing 6 “decor boards” or stages which depict a street, a region of rocks, a cemetery, a bedroom, a plain and an island; plus two sheets of pre-cut characters: a fire, a clock, an eye, a shell, two Citroën autmobiles (a 2CV and a DS), a wolfman, a blind man, a baby, a naked man, Death, a sleeping woman, and a truncated man.

“Sans prétendre atteindre à la rigueur d’un vrai test psychologique, TOPSYCHOPOR en utilise les principes. Il comprend six planches-décors et treize personnages ou objets. Le jeu consiste à choisir un décor et à y placer un ou plusieurs éléments découpés. ll suffit alors de se reporter au tableau des interprétations pour découvrir—avec horreur ou ravissement—ce que ce choix signifie. Le personnage ou l’objet choisi en premier lieu indique la tendance dominante du caractère du joueur, les éléments choisis ensuite viendront nuancer et compléter la première interprétation, selon un ordre d’importance décroissant. Certains objets ou personnages paraîtront peut-êtrc étranges; cela ne doit pas étonner, ils ont été voulus tels afin de faciliter les interprétations. Vous verrez d’ailleurs que vous vous familiariserez vite avec TOPSYCHOPOR et bientôt vous ressentirez la tentation de jouer avec lcs personnages sans plus vous soucier de leur signification. Car ce jeu cache son jeu, un jeu auquel vous vous prendrez. Pour l’interprétation des récits que vous ferez alors, vous pourrez toujours consulter votre psychiatre habituel.”

Rules of the game (autotranslated): “Without claiming to achieve the rigor of a real psychological test, TOPSYCHOPOR uses its principles. It includes six decor boards and thirteen characters or objects. The game consists of choosing a decor and placing one or more cut elements in it. It is then enough to refer to the table of interpretations to discover—with horror or delight—what this choice means. The character or object chosen in the first place indicates the dominant tendency of the player’s character, the elements then chosen will come to qualify and complete the first interpretation, in order of decreasing importance. Some objects or characters may appear strange; that should not surprise, they were wanted such in order to facilitate the interpretations. You will see that you will quickly become familiar with TOPSYCHOPOR and soon you will feel the temptation to play with the characters without worrying about their meaning. Because this game hides its game, a game that you will take. For the interpretation of the stories that you will then make, you can always consult your usual psychiatrist.”

I don’t have a copy of this, unfortunately (and please don’t tell me you have one to sell). Picture searches kept turning up links to film festivals which was a little confusing until I realised that there’s a short film by Antonin Peretjatko, Mandico et le TOpsychoPOR, about a man encountering the game.