Murder, My Sweet.

One of the bonuses of the Big Noir Watch was getting to see just how many dream/nightmare/hallucination sequences there were in the listed films besides those I remembered from previous viewings. The dream sequence is almost as old as cinema itself but the often lurid and melodramatic nature of noir storylines makes dreams and nightmares another recurrent feature of the the landscape. Beleaguered, paranoid characters are liable to find the Expressionist roots of noir cinema lurking behind their closed eyelids, ready to tip them into an unstable world of blurred vortices and looming, underlit faces.

Stranger on the Third Floor.

Production credits referred to these sequences (when they refer to them at all) as montages, a rather confusing term when montage is another word for film editing in general. The sequences were invariably the work of people other than the director, either a montage specialist or a photographer familiar with optical printing and camera effects. Before Don Siegel became a notable noir director he was a montage creator at Warner Brothers; the sequence showing the invasion of France in Casablanca is one of his. He credited his montage work with teaching him all about cinema craft.

The following examples are all the sequences I noticed during the recent noir binge. If you know of any other good ones from the 1940s or 1950s then please leave a comment.

Stranger on the Third Floor (1940)

An aspiring reporter is the key witness at the murder trial of a young man accused of cutting a café owner’s throat and is soon accused of a similar crime himself.

Alain Silver and Elizabeth Ward mark the beginning of what they term “the noir cycle” with The Maltese Falcon in 1941. But many other writers choose Stranger on the Third Floor as the beginning of the genre that would dominate the 1940s. With good reason: the film is 60 minutes of non-stop fear and paranoia photographed by Nicholas Musuraca, one of the RKO cinematographers whose use of shadows would help define the noir style. The celebrated dream sequence is almost a film in itself, with huge, shadow-filled sets in which reporter Mike Ward (John McGuire) undergoes accusation, an unwinnable trial and a slow walk to the electric chair.

Murder, My Sweet (1944)

After being hired to find an ex-con’s former girlfriend, Philip Marlowe is drawn into a deeply complex web of mystery and deceit.

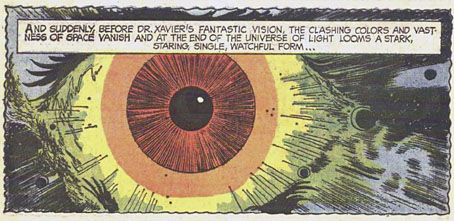

The first adaptation of Farewell, My Lovely changed the title so that viewers wouldn’t think it was another Dick Powell musical. As with The Big Sleep, the adaptation mangles the plot but it has its plus points, especially Mike Mazurki as Moose Malloy, an ex-wrestler whose performance as the overbearing ex-con is definitive. It also has this great hallucination sequence. In the novel Marlowe is blackjacked by rogue cops then wakes in a mysterious clinic with a head full of drugs. The film takes us inside Marlowe’s head during his unconscious episode, the Surrealist montage sequence being credited to Douglas Travers.

Conflict (1945)

An engineer trapped in an unhappy marriage murders his wife in the hope of marrying her younger sister.

Humphrey Bogart plays the scheming engineer who finds himself besieged by accusatory faces following a serious car crash. The sequence was directed by Roy Davidson with camera work by HF Koenekamp. Bogart’s dream includes repeated shots of swirling water racing down a plug-hole, a cheap vortex effect that reappears in later sequences.