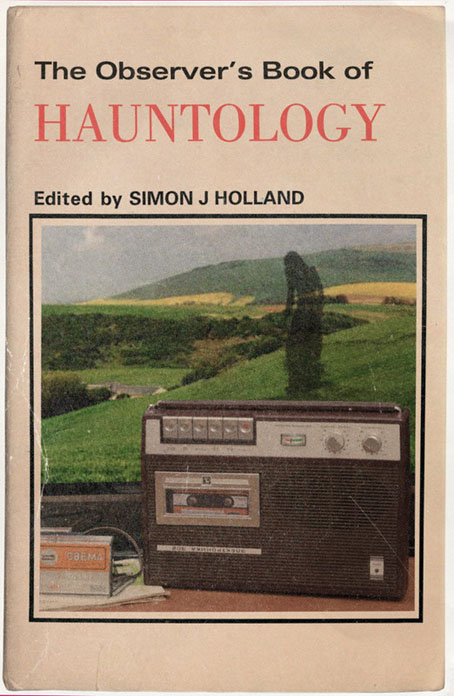

Goldmark hardcover, 1987.

The old maps present a sky-line dominated by church towers; those horizons were differently punctured, so that the subservience of the grounded eye, & the division of the city by nome-wound, was not disguised. Moving now on an eastern arc the churches of Nicholas Hawksmoor soon invade the consciousness, the charting instinct. Eight churches give us the enclosure, the shape of the fear; – built for early century optimism, erected over a fen of undisclosed horrors, white stones laid upon the mud & dust. In this air certain hungers were activated that have yet to be pacified; no turning back, as Yeats claims: “the stones once set up traffic with the enemy.”

—Iain Sinclair, Lud Heat

A serious house on serious earth it is

—Philip Larkin, Church Going

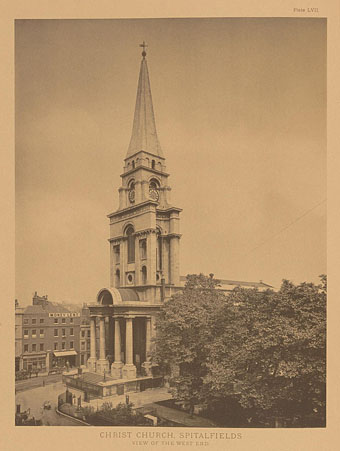

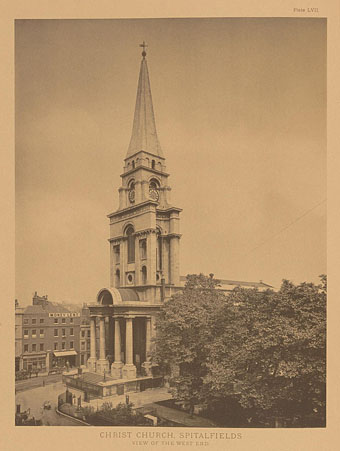

“Serious” is a word with many meanings. The Oxford English Dictionary gives one of these as “attended with danger; giving cause for anxiety”, a definition that wouldn’t suit Philip Larkin’s poem describing a visit to a moribund country church, but which is easily applied to a longer cycle of poems by Iain Sinclair. Lud Heat: A Book of the Dead Hamlets is the collection of writings that lifted Sinclair’s authorial profile out of the poetry ghetto in which he’d been situated throughout the 1970s. He published the first edition through his own Albion Village Press in 1975 but it wasn’t until the arrival of Peter Ackroyd’s Hawksmoor a decade later that wider public attention began to turn in Sinclair’s direction. Lud Heat set out for the first time a series of observations concerning the peculiar and sinister qualities of the churches built by Nicholas Hawksmoor in 18th-century London: Christ Church, Spitalfields; St George’s, Bloomsbury; St Mary Woolnoth; St George in the East; St Anne’s, Limehouse; St Alfege Church, Greenwich; plus those built in collaboration with John James: St Luke Old Street, and St John Horsleydown. The book separates the poetry with prose pieces—diary extracts, accounts of a film viewing and an art exhibition—that anticipate the author’s subsequent explorations of London’s margins and esoterica. Like many of Sinclair’s later writings, the texts in the early editions are accompanied by a variety of illustrations: engravings, contemporary photographs, and a map of London drawn by Brian Catling that posits a network of “lines of influence…invisible rods of force” connecting the churches with each other and with significant locations such as William Blake’s house, Cleopatra’s Needle and so on. Paperback reprints omitted the illustrations* but retained the map which was redrawn by Dave McKean. The new version gave greater emphasis to the Egyptian symbols that Sinclair and Catling had scattered across the city: jackal-headed Anubis as the presiding deity of the Isle of Dogs.

Photo by Charles Latham from London Churches of the XVIIth and XVIIIth Centuries (1896) by George H. Birch.

Lud Heat is a beguiling and potent book; it’s also a book that’s of its time in its suggestion of malefic “rods of force” scored across the capital. Sinclair’s map may be the earliest artistic development of a process begun in 1969 when John Michell published The View Over Atlantis, an elaboration of ideas set forth in another of his books, The Flying Saucer Vision. Michell’s free-wheeling speculations gave new life to the innocuous studies of Alfred Watkins, inflating amateur archaeological ruminations into full-blown Aquarian metaphysics. Where Watkins considered that “ley lines” (a term of his own invention) might have been ancient trading routes, Michell’s enthusiasm for the full range of Fortean phenomena transmuted the alleged paths into channels of unspecified “Earth energy”, flying-saucer guides, and the axes of a sacred geometry. Other crank scholars were eager to follow Michell’s lead, leaving an opening for Sinclair to adopt the conceit for its poetic resonances; the New Age trappings were inverted to reveal a darker pattern more suited to London’s history of plague, murder and mass destruction. (The Hawksmoor churches had been built to compensate for the devastations of the Great Fire of 1666; two of them were hit by bombs during the Blitz, with one being damaged beyond repair.)

This isn’t to suggest that Sinclair was borrowing directly from Watkins and Michell; in an interview he mentions an earlier precursor of both his map and Watkins’ ley lines in Prehistoric London: Its Mounds and Circles (1914) by Elizabeth O. Gordon. But something was in the air in the 1970s. Lud Heat appeared shortly before the release of a pair of albums that borrowed heavily from Michell’s books—Green (1978) by Steve Hillage, and Blake’s New Jerusalem (1978) by Tim Blake—while two TV serials exploited the idea of ley lines as channels of Earth energy, Children of the Stones (1977) and Nigel Kneale’s Quatermass (1979). Lud Heat stands apart from these works by concentrating on urban structures rather than isolated monoliths and ancient pathways. The suggestion that the city of London could be home to mysterious “rods of force” is an especially intriguing one, hence the appropriation of the idea by Peter Ackroyd in Hawksmoor and Alan Moore in From Hell. Any church of a sufficient size or age is a kind of time machine, maintaining in its appearance and its grounds a pocket of history separated from the changes that take place around it. The churches in Lud Heat are also batteries of stone, impregnated with the unspent energies of the dead who lie in their crypts. These latent forces overflow their containers, spilling into the streets beyond the church walls. Sinclair has always been adamant that his Lud Heat map is a fabrication; the degree to which he believes in the rest of his thesis is for the reader to decide. It is a fact that St George in the East is close to the location of the Ratcliffe Highway Murders of 1811 (Sinclair includes a illustration of the murderer’s corpse in Lud Heat), while Christ Church, Spitalfields, sits at the centre of maps of the Jack the Ripper murders; the fifth and most brutal of these occurred a short distance from that colossal porch on the opposite side of Commercial Street. “Dead Hamlets” also has many meanings.

Continue reading “Serious houses: The Lud Heat Tapes, 1979”