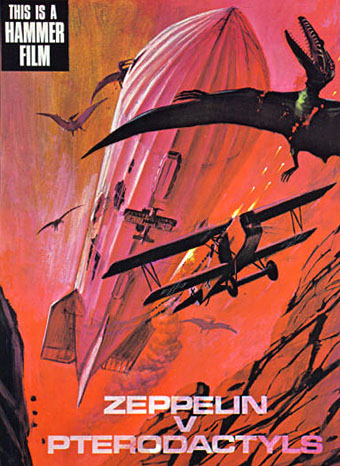

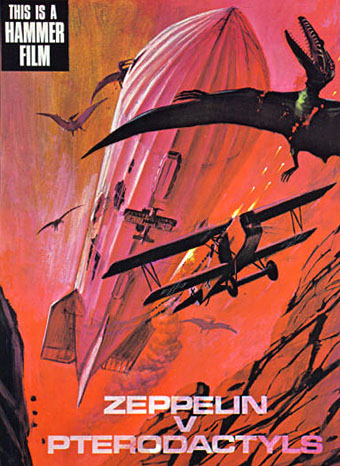

An unmade high-concept from Hammer Films’ early Seventies dalliance with pulp adventure, if you must know. Via Boing Boing via Jess Nevins via Airminded where we learn:

The story was along the lines of THE LAND THAT TIME FORGOT, with a German Zeppelin being blown off-course during a bombing raid on London and winding up at a “lost continent”-type place.

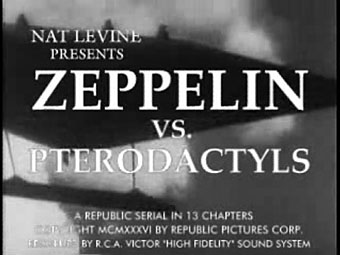

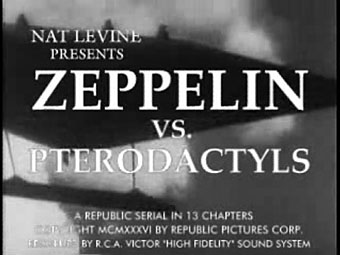

Rather like the Civil War balloon that’s blown off-course in Jules Verne’s Mysterious Island then, which ends up on Captain Nemo’s volcanic island of giant birds and insects. Of course, the mere fact that a film was never made is no obstacle for YouTube’s army of diligent mash-up artists and you can see Zeppelin v. Pterodactyls re-imagined as a 1936 Republic Serial here. (And on a pedantic professional note, an older font should have been used for the titles since Hermann Zapf didn’t design Palatino until the 1940s.)

It was another horror company, Amicus Productions, that produced The Land that Time Forgot (1975) (and its ER Burroughs-derived sequels, At the Earth’s Core [1976] and People that Time Forgot [1977]) so this Hammer concept may have been an attempt to follow Amicus’s lead and exploit the momentary flush of enthusiasm for ERB and co. Or perhaps they thought that Zeppelin movies were the next big thing after Michael York’s First World War adventure, Zeppelin, in 1971. No one in Hollywood these days would dare finance a film with a title like this. The same dumbing-down imperative that gave us Harry Potter and the Sorceror’s Stone (because Americans can’t be trusted to know what the Philosopher’s Stone is) would no doubt want “pterodactyls” replaced by “dinosaurs” or the wording of the whole thing reduced to ZvP.

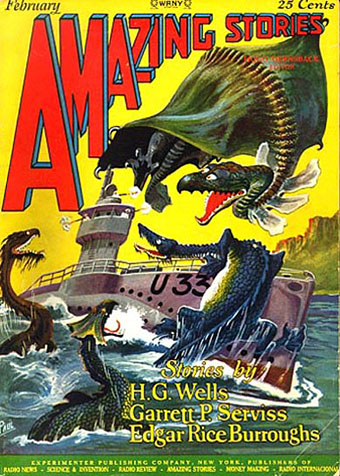

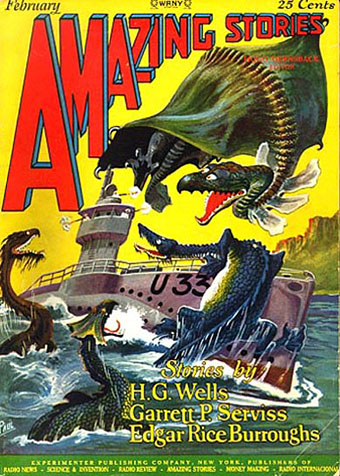

U-boat vs. dinosaurs! Illustration by Frank R Paul for a 1927 reprint of The Land that Time Forgot.

The Land that Time Forgot was scripted by Michael Moorcock and New Worlds‘ (and Savoy Books) illustrator James Cawthorn. The pair did a decent job with the story although the film as a whole is let-down by silly monster effects, the pterodactyl (or is it a pteranodon?) in this instance being a lifeless thing swinging from a crane. Moorcock and Cawthorn worked together on Tarzan Adventures which Moorcock was editing as a teenager so they appreciated the material at least. This wasn’t the only connection New Worlds had with pulp cinema, more surprisingly JG Ballard had provided a story for Hammer in 1970 with When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth. Hammer missed an opportunity in not hiring Moorcock for something seeing as he’d just written one of the first retro-dirigible (and pre-Steampunk) novels, The Warlord of the Air, in 1971. UK film producers had some of the best writers in the world under their noses yet could only offer them trash to work on. No wonder the British film industry went down the tubes in the Seventies after the American funding dried up.

My favourite pulp adaptation from Hammer is The Lost Continent based on Uncharted Seas by Dennis Wheatley. A typical Hammer product in the way the story is frequently preposterous yet the whole thing is made with the utmost seriousness. Amazon summarises the plot, such as it is:

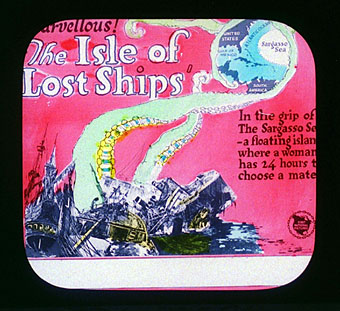

This film starts out like The Love Boat on acid, as a cast of unpleasant characters, all with horrible secrets, take a chartered cargo ship to escape their troubles. Unfortunately, the leaky ship is carrying an explosive that can be set off by sea water and it sinks, stranding many characters in a Sargasso Sea populated by man-eating seaweed, giant monster crabs and turtles, and some Spanish conquistadors who think the Inquisition is still on.

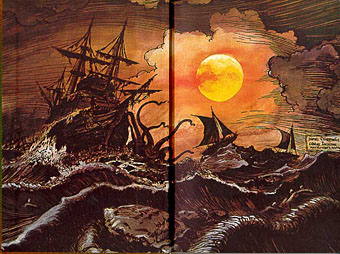

Eric Porter is the ship’s captain, a very good actor who was superbly sinister and convincing as Professor Moriarty in Granada TV’s Sherlock Holmes adaptations. The Lost Continent was Wheatley’s shameless plundering of William Hope Hodgson’s Sargasso Sea tales, the book being originally written in 1938 when Hodgson was less well-known than he is today. Until the Pirates of the Caribbean films this was about the closest thing on screen to Hodgson’s world of drifting weed, lost galleons and man-eating monsters, so there you have its cult value. Just be ready with the fast forward button if you try and watch it.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Moorcock on Ballard

• Coming soon: Sea Monsters and Cannibals!

• Revenant volumes: Bob Haberfield, New Worlds and others

• Druillet meets Hodgson

• Davy Jones

• The Absolute Elsewhere