Fantastic Sea Carriage (1556) by Johannes van Doetecum the Elder.

• I’ve grown increasingly tired of Kubrick-related micro-fetishism (despite contributing to it myself with previous posts) but this piece at Film and Furniture about the history of David Hicks’ Hexagon carpet design is a good one.

• “In hindsight, we can see how rarely one technology supersedes another…” Leah Price on the oft-predicted, never arriving death of the book.

• From Rome To Weston-Super-Mare: Eden Tizard on Coil’s Musick To Play In The Dark.

“It is,” the editor of the London Sunday Express had written nine years earlier, sounding like HP Lovecraft describing Necronomicon:

the most infamously obscene book in ancient or modern literature….All the secret sewers of vice are canalized in its flood of unimaginable thoughts, images and pornographic words. And its unclean lunacies are larded with appalling and revolting blasphemies directed against the Christian religion and against the name of Christ—blasphemies hitherto associated with the most degraded orgies of Satanism and the Black Mass.

Regarded as a masterpiece by contemporary writers such as TS Eliot and Ernest Hemingway, celebrated for being as difficult to read as to obtain, Ulysses had been shocking the sensibilities of critics, censors, and readers from the moment it began to see print between 1918 and 1920, when four chapters were abortively serialized in the pages of a New York quarterly called The Little Review. Even sophisticated readers often found themselves recoiling in Lovecraftian dread from contact with its pages. “I can’t get over the feeling,” wrote Katherine Mansfield, “of wet linoleum and unemptied pails and far worse horrors in the house of [Joyce’s] mind.” Encyclopedic in its use of detail and allusion, orchestral in its multiplicity of voices and rhetorical strategies, virtuosic in its technique, Ulysses was a thoroughly modernist production, exhibiting—sometimes within a single chapter or a single paragraph—the vandalistic glee of Futurism, the decentered subjectivity of Cubism, the absurdist blasphemies and pranks of Dadaism, and Surrealism’s penchant for finding the mythic in the ordinary and the primitive in the low dives and nighttowns of the City.

Michael Chabon on the US trial of James Joyce’s Ulysses

• Mix of the week: Through A Landscape Of Mirrors Vol. III—France II by David Colohan.

• Another Not The Best Ambient And Space Music Of The Year Post by Dave Maier.

• Sarah Angliss and friends perform Air Loom at Supernormal, 2019.

• Out next month: The World Is A Bell by The Leaf Library.

• Amy Simmons on where to start with Pier Paolo Pasolini.

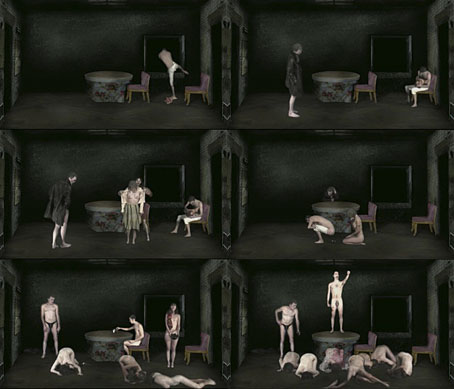

• At Dennis Cooper’s: Candy Clark Day.

• Uccellacci E Uccellini (1966) by Ennio Morricone | Liriïk Necronomicus Kahnt (1978) by Magma | Ostia (The Death Of Pasolini) (1986) by Coil