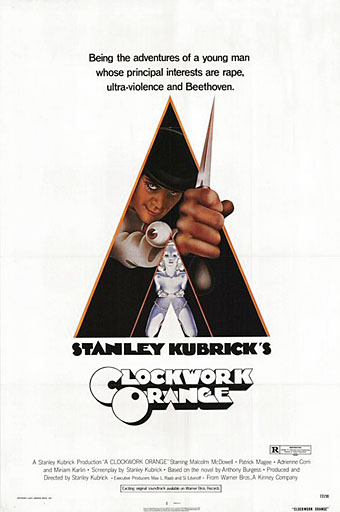

Philip Castle’s poster design. Castle also created the artwork for Full Metal Jacket.

Searching through old magazines whilst researching the epic Barney Bubbles post turned up this, a short reaction by Anthony Burgess to the success of Stanley Kubrick’s Clockwork Orange. Burgess became increasingly ambivalent about the attention brought about by Kubrick’s adaptation, not least because of the way it dominated the rest of his career; some of that ambivalence is already in evidence here.

Juice from A Clockwork Orange

by Anthony Burgess

Rolling Stone, June 8th, 1972

WHEN IT WAS first proposed about eight years ago, that a film be made of A Clockwork Orange, it was the Rolling Stones who were intended to appear in it, with Mick Jagger playing the role that Malcolm McDowell eventually filled. Indeed, it was somebody with the physical appearance and mercurial temperament of Jagger that I had in mind when writing the book, although pop groups as we know them had not yet come on the scene. The book was written in 1961, when England was full of skiffle. If I’d thought of giving Alex, the hero, a surname at all (Kubrick gives him two, one of them mine), Jagger would have been as good a name as any: it means “hunter,” a person who goes on jags, a person who doesn’t keep in line, a person who inflicts jagged rips on the face of society. I did use the name eventually, but it was in a very different novel—Tremor of Intent—and meant solely a hunter, and a rather holy one.

I’ve no doubt that a lot of people will want to read the story because they’ve seen the movie—far more than the other way around—and I can say at once that the story and the movie are very like each other. Indeed, I can think of only one other film which keeps as painfully close to the book it’s based on—Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby. The plot of the film is that of the book, and so is the language, although naturally there’s both more language and more plot in the book than in the film. The language used by Alex, my delinquent hero, is called Nadsat—the Russian suffix used in making words like fourteen, fifteen, sixteen—and a lot of the terms he employs are derived from Russian. As these words are filtered through an English-speaking mind, they take on meanings and associations unknown to Russians. Thus, Alex uses the word horrorshow to designate anything good—the Russian root for good is horosh—and “fine, splendid, all right then” is the neuter form we ought really to spell as chorosho (the ch is guttural, as in Bach). But good to Alex is tied up with performing horrors, and when he is made what the State calls good it is through the witnessing of violent films—genuine horror shows. The Russian golova—meaning head—is domesticated into gulliver, which reminds the reader he is taking in a piece of social satire, like Gulliver’s Travels. The fact that Russian doesn’t distinguish between foot and leg (noga for both) and arm and hand (ruka) serves—by suggesting a mechanical doll—to emphasise the clockwork-view of life that Alex has: first he is self-geared to be bad, next he is state-geared to be good.