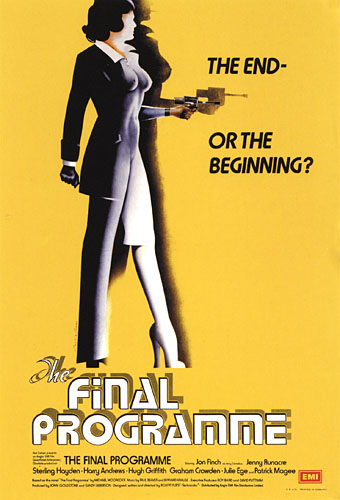

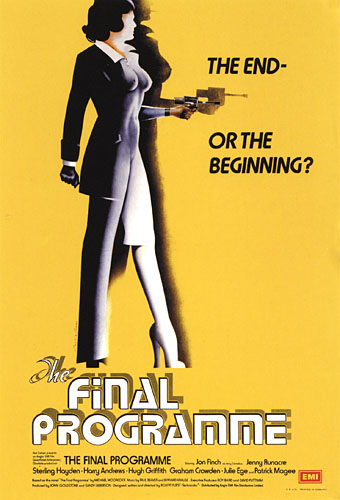

The Final Programme (1973). Philip Castle’s poster art implied the androgynous finale of Moorcock’s novel which the film itself evaded.

They were musty-smelling 10p messages from the futuristic past, complete with cover designs (and content) that were unlike anything I’d seen before. I’m fairly certain that this was how I first came across Michael Moorcock, in an early-70s Mayflower paperback, with a psychedelic cover by Bob Haberfield.

(…)

Moorcock steered New Worlds towards a set of concerns that chimed with the times; this was the period ruled by Marshal McLuhan and RD Laing, and the exploration of “inner space” seemed just as interesting as the “outer space” of satellites and moonshots. This turn was controversial, not just with die-hard pulp fans, but, surprisingly, with people such as the pop artist Richard Hamilton, another denizen of the London scene. “He thought we were turning science fiction into something namby-pamby, losing its roots,” Moorcock says. “He wanted explosions and spaceships and robots.”

• When Hari Kunzru met Michael Moorcock, a major feature on a great writer and cultural catalyst. Kunzru posted the full transcript of their conversation here. Jovike’s Moorcock Flickr set has many of the lurid Mayflower covers.

• Moorcock is among the contributors to the forthcoming Thackery T. Lambshead Cabinet of Curiositities. io9 posted a list of contents (and one of my pics) while co-editor Jeff VanderMeer added some detail.

• So long to The White Stripes whose dissolution was announced earlier in the week. We know they’ll be back one day. Jay Babcock gave them their first major interview for the LA Weekly in 2000 which he’s reposted here.

• Mister Blues (1962) by Lasry-Baschet aka Structures Sonores, a rare 7″ single showcasing the unique glass-and-metal sounds of the Cristal Baschet. Young Teddy Lasry on clarinet was playing in prog-jazz outfit Magma a few years later. Related: John Payne on Magma and The Mars Volta.

Here’s one thing that changed me: a close reading of Flannery O’Connor’s Mysteries and Manners. In it, she says that, “it is the business of fiction to embody mystery through manners,” manners being those concrete details — depictions of the real — in story. “Mystery through manners…” I had never heard a modern author seeking deep metaphysical mystery through realism before. Well, sure, Robert Musil, Bruno Schulz, Robert Walser, and a handful of other personal faves. By deep mystery I mean, mystery about our relationship with the planet, not anthropocentric mystery. I get sick of thinking about humans quickly, as we only constitute about 1% of what’s happening in our universe, if that much, and it was refreshing to me to hear O’Connor critiquing Henry James’ idea that modern people should aspire to know nothing of mystery, to be completely rooted in humanity. That notion makes me feel like hurling myself off a cliff. In her opinion, great literature seeks to embrace and express mystery through its mimicry of actual mannerisms. Mystery — fantasy — through the real. And with that, the borders between fantasy and realism were completely transgressed in my brain. Suddenly, I saw them as two good means to the same end. This made me excited to write real human situations again.

Trinie Dalton is interviewed here.

• And speaking of mystery through the real, there’s London Intrusion, a sequence of metropolitan adumbrations by China Miéville. Am I the only person to spot an intrusion of a different kind in the presence there of one of Eugène Atget’s Parisian views? There’s a doorway to Viriconium in that curious wedge of buildings but nobody can tell you where.

• Rupert Murdoch—A Portrait of Satan. Adam Curtis on top form looking at the Dirty Digger’s career and a reminder of why some of us have always called one of his rags The Scum. A key point for me: Murdoch’s insecure railing against “elites”, a favourite term of aspersion on his Fox News network.

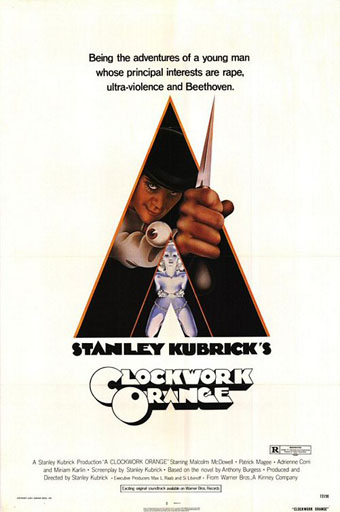

• Rick Poynor asks What Does JG Ballard Look Like? Related: “…only two people in Bucharest are going to read this.” Eduardo Paolozzi in conversation with JG Ballard and Frank Whitford, 1971.

• How many days does Bill Murray’s character really spend reliving Groundhog Day?

• Silent Porn Star explores The Translucent Beauty of Androgyny.

• Ballets Russes brought back to life on film, and also here.

• Dewanatron Electronic Music Instruments.

• RIP Tura Satana. Remember her this way.

• Warm Leatherette (1978) by The Normal | Warm Leatherette (1982) by Grace Jones | Warm Leatherette (1998) by Chicks On Speed.