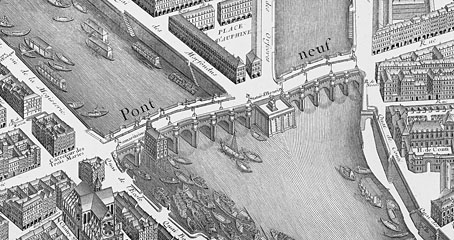

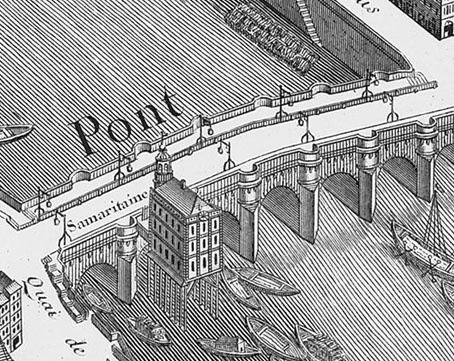

Yesterday’s map of Portmeirion presented a style of mapping I’ve always enjoyed, with the scale of buildings and roads exaggerated in order to give a better impression of the various locations for navigation purposes. The most elaborate example of this kind of isometric projection—indeed, the undoubted nonpareil—is the Turgot Map of Paris, named after its commissioner Michel-Étienne Turgot. The map was issued originally in a series of 20 engraved plates from 1734–1736, and for a long time I only knew of it via the (frustratingly uncredited) details printed on endpapers of the German first edition of Perfume by Patrick Süskind. Once again the web managed to solve another of those nagging artistic riddles.

We’re told that one Louis Bretez was contracted by Monsieur Turgot to draw up the plans of the city which apparently took him two years. Once you start scrutinising the detail it’s surprising it didn’t take a lot longer. Claude Lucas was responsible for the meticulous engravings which show how Paris appeared before Baron Haussmann set to work demolishing many of the medieval streets.

Wikimedia Commons has the entire map in a variety of sizes up to a hefty 6,552 × 5,101 pixels. At the Kyoto University Library it’s possible to view the plates individually with each plate subdivided into detailed views. There’s also a 1908 reprinting of the plates at the Internet Archive. Despite the depredations of Hausmann and co., central Paris has survived a lot better than many other European cities. London suffered so badly during the Second World War it’s a shame we don’t have an equivalent view of the pre-Luftwaffe capital.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The etching and engraving archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• In the Village

• Compass roses

• Charles Méryon revisited

• The art of Sydney R Jones, 1881–1966

• Perfume: the art of scent