Pop Surrealism, 1949.

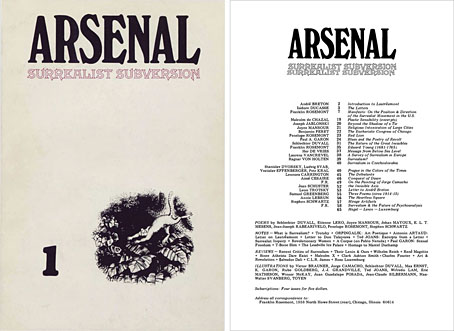

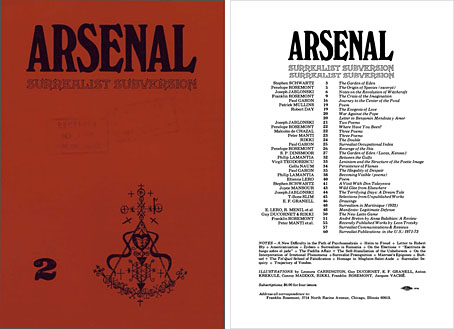

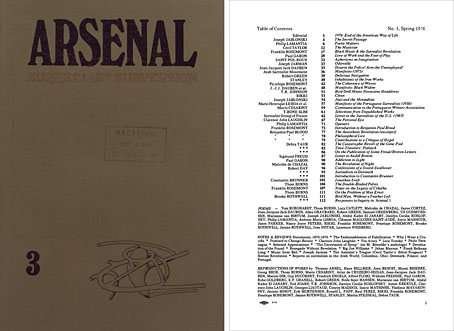

More from the Chicago Surrealists. The discovery of the first item comes via a comment from Paul (thanks!) in the post about Arsenal magazine which directed my attention to Monoskop where there’s another publication, Cultural Correspondence, related to the Chicago Surrealist Group. Cultural Correspondence was a US journal which ran for 14 issues from 1975 to 1981. Searching around for more information revealed an archive of the entire run at Brown University:

A journal born from the collapse of the New Left and hopes for a new beginning of a social movement, but also of left-wing thinking about culture, Cultural Correspondence was in many ways a unique publication.

Its founding editors, Paul Buhle and Dave Wagner, had both served on the editorial board of the journal Radical America, founded in 1967. Buhle had been the founder of that bi-monthly journal, creating it out of a network of activist-intellectuals in the Students for a Democratic Society; Wagner was officially “Poetry Editor,” but after its shift from Madison, Wisconsin, to the Boston area in 1971, he became a member of an expanded board of editors. Together they taught at the Cambridge-Goddard Graduate School, then Wagner left for Europe and Buhle left the editorial board, moving to Yonkers. An exchange of letters from these locations spawned the notion of a new publication. It was to be the first radical magazine put out by members of a generation that had since childhood watched television and appreciated as well as enjoyed a considerable portion of it, also films and “pulp” literature.

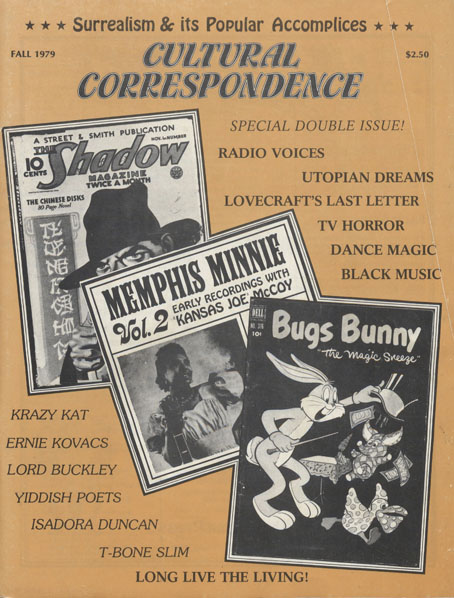

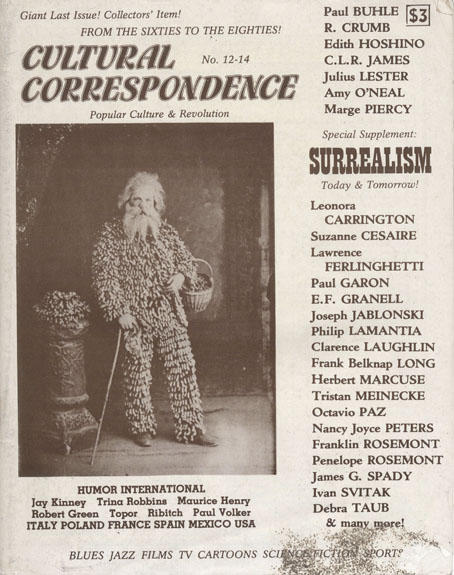

The issue at Monoskop was the penultimate one (numbered 10/11), guest-edited by Franklin Rosemont who took the opportunity to give the readers an exploration of “Surrealism and Its Popular Accomplices”. The final issue (numbered 12–14) continued the theme with a Surrealist supplement.

Even without the Surrealist content, Cultural Correspondence is an interesting magazine, closer to the era’s underground magazines than an arts publication, especially in its attention to the underground cartoonists. Given my general antipathy to arts magazines I find this very much in its favour. The Rosemont-edited issue shows a different side of the Chicago group when compared to the more pugnacious Arsenal, with no sign of the scowling ideologues that fill the pages of the Surrealist journal. HP Lovecraft turns up once again (musings about Surrealism from his very last letter), together with Rosemont’s beloved blues musicians. Rosemont also reprints the short essay about pulp fiction by Robert Allerton Parker, Explorers of the Pluriverse, which appeared in the catalogue for First Papers of Surrealism.

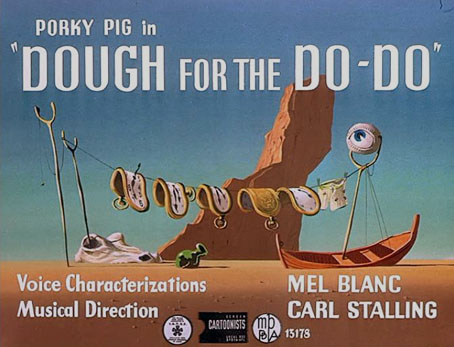

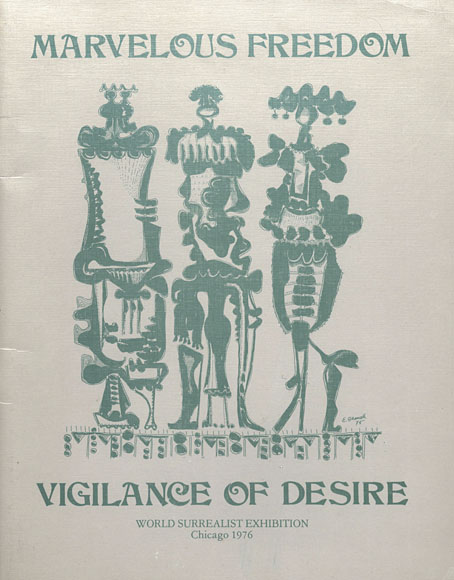

Meanwhile, at the Internet Archive there’s Marvellous Freedom, Vigilance of Desire, the exhibition programme for the World Surrealist Exhibition which was staged in Chicago in 1976. Penelope Rosemont refers to this event several times in Surrealist Women so it’s great to be able to see some of the artworks which are only described in brief in the book. Many exhibition catalogues are mere lists of pictures with an essay or two but this one looks like it took the First Papers of Surrealism catalogue as its model, being filled with essays, poems, small illustrations and so on. The early Surrealist exhibitions were never satisfied with scattering artworks around an otherwise empty room, several of them extended their themes into the exhibition space in early manifestations of the installation or environment concept. For the Chicago event the visitor passed through “Sleepwalker’s Hill” into the “Corridor of the Forgotten Future”, which led to the heart of the exhibition and eleven “Domains of Surrealist Vigilance” dedicated to significant figures: Lewis Carroll’s Alice, the Duchess of Towers (from one of Andre Bréton’s favourite films, Peter Ibbetson), Sade’s Juliette, Harpo Marx, T-Bone Slim, Peetie Wheatstraw, Robin Hood, Bugs Bunny, Alfred Jarry’s Doctor Faustroll, Melmoth the Wanderer, and the Surrealists’ favourite master criminal, Fantômas. The imperishable wise-cracking rabbit had already appeared in the pages of Arsenal, as well as on the cover of the first issue of Cultural Correspondence, but this is where he becomes a genuine Surrealist icon.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The Surrealism archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Arsenal: Surrealist Subversion