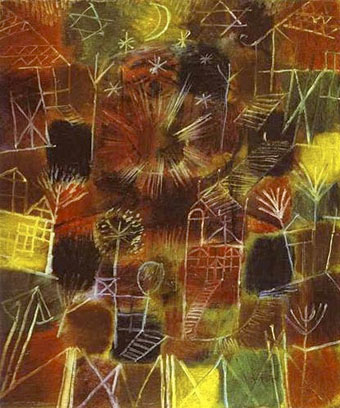

Angelus Novus (1920) by Paul Klee.

• “Compared to [László] Krasznahorkai’s earlier fiction, Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming is funnier and more stylistically accessible—despite its length and seemingly endless sentences—but it is also his most unremittingly ruthless work,” says Holly Case. Elsewhere: “Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming may not bring joy or consolation, but reading it is a mesmerisingly strange experience: a slab of late modernist grindcore and a fiercely committed exercise in blacker-than-black absurdity,” says Sukhdev Sandhu.

• Zeitraffer (“Time-lapse“) is an exhibition devoted to Tangerine Dream which opens at the Barbican, London, in January. Also coming in January is a new album, Recurring Dreams, by the current iteration of the group which will be available on CD and double vinyl. I was impressed by the last TD release, Quantum Gate, so I’m looking forward to this even if it is only a reworking of popular pieces from the Virgin years.

• RIP Gershon Kingsley, an electronic music pioneer best known for the silly but fun albums he made with Jean-Jacques Perrey, and for being the composer of that evergreen synthesizer novelty, Popcorn.

The first major study in English of ancient Greek sexuality—especially the way relationships between men were both common and celebrated as a perfect embodiment of love—A Problem in Greek Ethics helped set the stage for the modern-day gay rights movement. But it did so surreptitiously, behind closed doors, as required by the times. Symonds printed it privately in 1883; a print run of just 10 copies reduced the risk that it would fall into the wrong hands. The typesetter complained about the content. Symonds circulated it cautiously, to people he trusted or had reason to think would be discreet. Until now, researchers believed that only five copies survived.

Rachel Wallach on the discovery of a sixth copy of John Addington Symonds’ landmark study

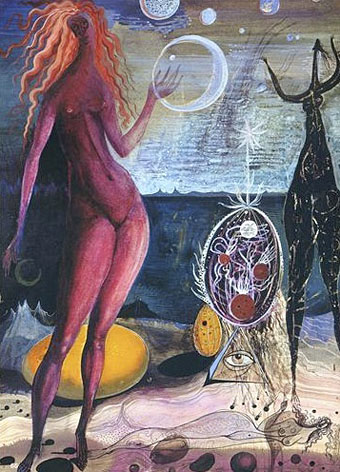

• Contagious Magick of the Super Abundance is a book of art by the late Ian Johnstone, former partner of John Balance and cover artist for some of the last releases by Coil.

• Dennis Cooper‘s favourite fiction, poetry, non-fiction, film, art, and internet of 2019. Thanks again for the link here!

• At the BFI: Hannah McGill on the umbrellas of cinema, and Jasper Sharp on 10 essential films by Yasujiro Ozu.

• Bobby Krlic, aka The Haxan Cloak, talks to Claire Lobenfield about creating the soundtrack for Midsommar.

• Joker and Chernobyl composer Hildur Gudnadóttir: “I’m treasure hunting”.

• Joshua Rothman on how William Gibson keeps his science fiction real.

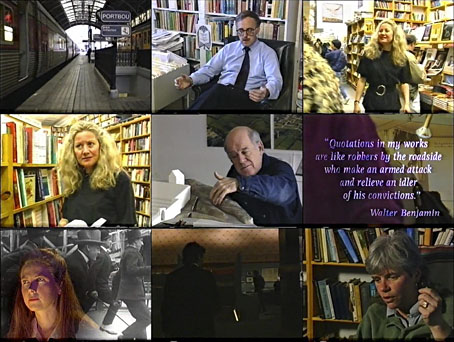

• Samantha Rose Hill on Walter Benjamin’s last work.

• Scientific phenomena photographs of the year.

• The Dream Before (1989) by Laurie Anderson | Angel Tech (1994) by The Grid feat. Sheila Chandra | Angel Tech (1994) by Pete Namlook & Bill Laswell