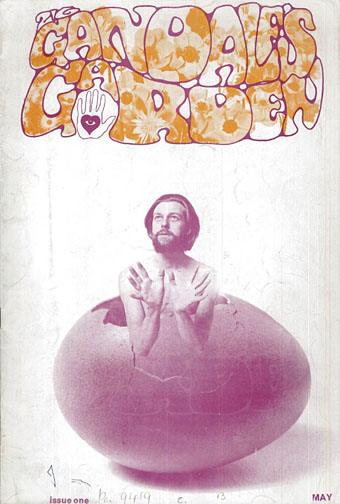

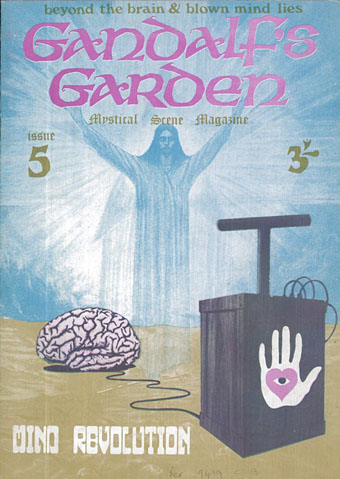

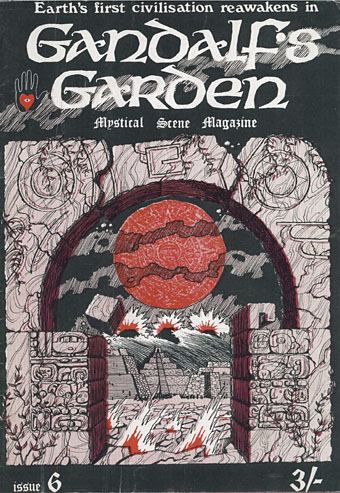

It’s taken a while but this short-lived underground magazine has finally been scanned and posted online. (It’s actually been available since 2019 but I only just discovered it.) Gandalf’s Garden was a small British publication, edited by Muz Murray, that preferred the definition “overground” to “underground”. Six issues were published in London from 1968 to 1969. There was also an affiliated shop of the same name situated in the World’s End area of Chelsea.

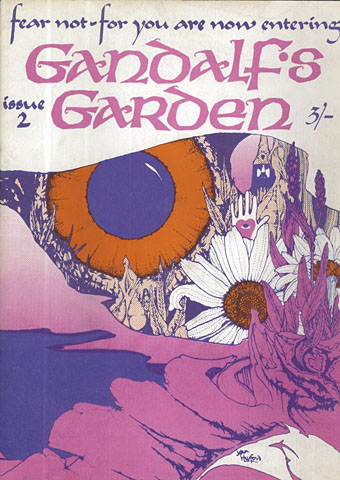

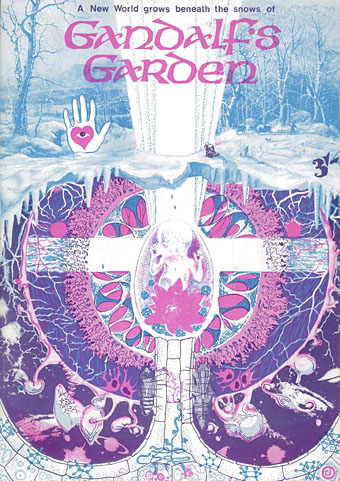

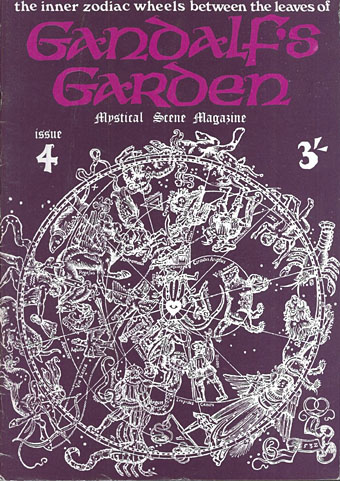

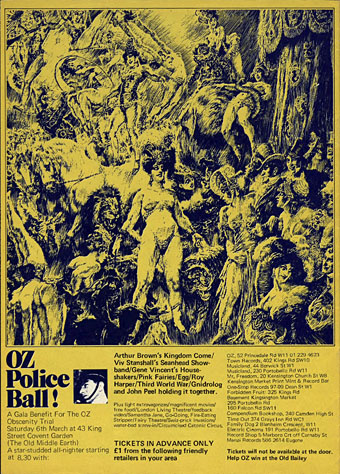

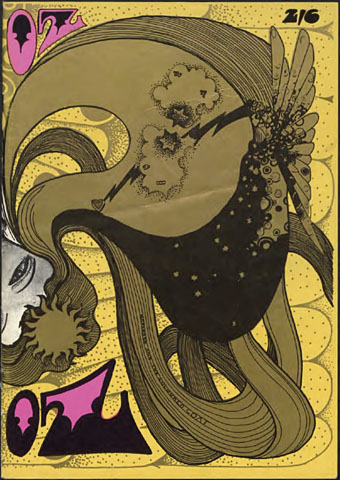

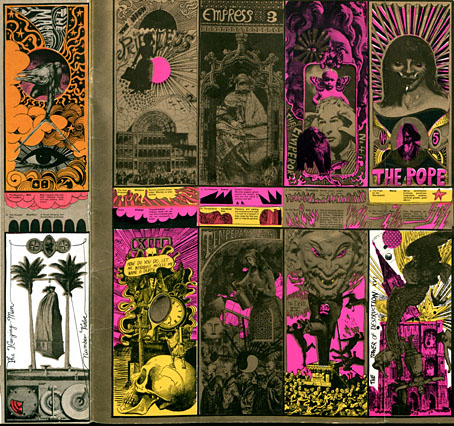

Having only seen a few sample pages before now it’s been good to look through the magazine’s entire run. The editorial attitude was very different to the often strident and aggressive Oz, with whom it shared a cover artist, John Hurford. Political revolution was a recurrent obsession in the pages of Oz—for some of the writers, anyway—and for a few months seemed like a tangible possibility following the events in Paris in May, 1968. The political stance of Gandalf’s Garden was more concerned with a revolution in the head, reflecting the philosophical side of hippy culture: Eastern religion, occultism, Earth mysteries and so on; issues four to six were subtitled “Mystical Scene Magazine”. The most well-known contributor was BBC radio DJ John Peel who wrote a short column for the first couple of issues, a reminder that the Peel public persona in the late 1960s was very different from the sardonic champion of all things punk ten years later. “Never trust a hippy” unless that hippy can make you famous by playing your singles on his radio show…

Peel doesn’t say much about music in his columns, but music was a staple subject of the underground mags, so Gandalf’s Garden has interviews with the Third Ear Band, Marc Bolan, The Soft Machine and Quintessence. Meanwhile, Donovan pops up in the letters page, sending the staff good wishes and his greetings to “Lemon” Peel.

There’s also a letter from Brinsley Le Poer Trench, 8th Earl of Clancarty, asking to be put on the magazine’s mailing list. Trench was a notable flying-saucer obsessive (previously) who I expect would have enjoyed the features by Colin Bord about the UFO worshippers of the Aetherius Society, and the lost continent of Mu. I only found out recently that Bord began his writing and photography career in these pages (see this Wormwoodiana post which leads to this interview with Janet Bord). Janet and Colin Bord put together a series of popular guides in the 1970s and 80s to Britain’s mystic and mythic sites, good books on the whole if you approach them with a sceptical frame of mind. The Bords never ventured as far into the crankosphere as John Michell but they follow the Michell thesis about Alfred Watkins’ ley lines being channels of “Earth energy” rather than trading routes. (Archaeologists have never accepted any of these theories.) The readers of Gandalf’s Garden were the target audience for this kind of thing—issue four has a feature about Katharine Maltwood’s spurious but fascinating “Glastonbury Zodiac”—and sure enough there’s an ad for Michell’s landmark treatise, The View Over Atlantis, in the final issue. In this respect the magazine was probably ahead of its time, folding just as a wave of general interest in all manner of esoteric subjects was about to break. With better funding (and a replacement for its franchise-baiting title) Gandalf’s Garden might have found a niche as an early New Age publication.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Oz magazine online

• The Trials of Oz

• Early British Trackways

• The art of John Hurford