left: Maggi Hambling’s Oscar Wilde monument near Covent Garden, London.

“Yes, we shall win in the end; but the road will be long and red with monstrous martyrdoms.” Oscar Wilde, after his release from Reading Gaol in 1897.

“Forty years ago in Britain, loving the wrong person could make you a criminal. Smiling in the park could lead to arrest and being in the wrong address book could cost you a prison sentence. Homosexuality was illegal and hundreds of thousands of men feared being picked up by zealous police wanting easy convictions, often for doing nothing more than looking a bit gay.

“At 5.50am on 5 July 1967, a bill to legalise homosexuality limped through its final stages in the House of Commons. It was a battered old thing and, in many respects, shabby. It didn’t come close to equalising the legal status of heterosexuals and homosexuals (that would take another 38 years). It didn’t stop the arrests: between 1967 and 2003, 30,000 gay and bisexual men were convicted for behaviour that would not have been a crime had their partner been a woman. But it did transform the lives of men like Antony Grey, who had fought so hard for it, meaning that he and his lifelong partner no longer felt that every moment of every day they were at risk.”

From “Coming out of the dark ages” by Geraldine Bedell, The Observer.

The Sexual Offences Act of 1967, passed forty years ago today, was a compromised victory, as the quote above notes. The age of consent was set higher for gay men at 21 (these laws and restrictions applied to men only?lesbian sex had never been forbidden), you couldn’t be a member of the armed forces, you had to conduct your business with one other person only and in private (ie: at home; no hotel liaisons). The new act also only applied to England and Wales; Scotland had to wait until 1980 while in Northern Ireland (often a backwater where gay rights are concerned) the law wasn’t changed until 1982.

Yet it was a start, and it’s surprising and heartening to see how far things have travelled since 1967, especially when we seemed to be moving in reverse with the iniquities of the Thatcher years. Tony Blair’s government can be accused of many sins but it was never homophobic, and gave us an equalised age of consent, civil unions and finally scrapped Thatcher’s Section 28 law forbidding “the promotion of homosexuality”. Yes, gay-bashing still occurs, gay teens are bullied at school and we still have people like this idiot spouting nonsensical drivel. But Britain finally feels like a civilised place these days, more than it ever did.

It took over a century Oscar, and the road was long and red, but we made it.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Joe Orton

• The Poet and the Pope

• Queer Noises

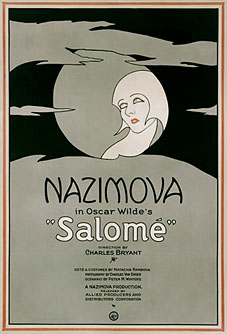

We tend to think of cinema as a modern medium, quintessentially 20th century, but the modern medium was born in the 19th century, and the heyday of the Silent Age (the 1920s) was closer to the Decadence of the fin de siècle (mid-1880s to the late-1890s) than we are now to the 1970s. This is one reason why so much silent cinema seems infected with a Decadent or Symbolist spirit: that period wasn’t so remote and many of its more notorious products cast a long shadow. Even an early science fiction film like Fritz Lang’s Metropolis has scenes redolent of late Victorian fever dreams: the vision of Moloch, Maria’s parable of the tower of Babel, the coming to life of statues of the Seven Deadly Sins, and—most notably—the vision of the Evil Maria as the Whore of Babylon. Woman as vamp or

We tend to think of cinema as a modern medium, quintessentially 20th century, but the modern medium was born in the 19th century, and the heyday of the Silent Age (the 1920s) was closer to the Decadence of the fin de siècle (mid-1880s to the late-1890s) than we are now to the 1970s. This is one reason why so much silent cinema seems infected with a Decadent or Symbolist spirit: that period wasn’t so remote and many of its more notorious products cast a long shadow. Even an early science fiction film like Fritz Lang’s Metropolis has scenes redolent of late Victorian fever dreams: the vision of Moloch, Maria’s parable of the tower of Babel, the coming to life of statues of the Seven Deadly Sins, and—most notably—the vision of the Evil Maria as the Whore of Babylon. Woman as vamp or

Irony never rests in the world of religion these days. I suspect Oscar would be pleased by this attention, he had an audience with Pius IX when he was a young man and wrote a poem,

Irony never rests in the world of religion these days. I suspect Oscar would be pleased by this attention, he had an audience with Pius IX when he was a young man and wrote a poem,