Death in Genoa | Simon Callow plays Oscar Wilde in a drama available as a free download.

Tag: Oscar Wilde

The end of Orpheus

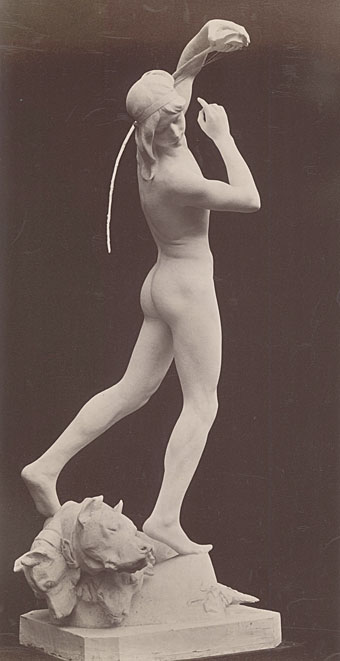

Orphée endormant Cerbère by Henri Peinte (1887).

It’s often difficult to imagine a perfectly innocent motive when looking at works such as these. Did the world really need another statue of Orpheus or is the true intention revealed by those carefully sculpted buttocks, with the mythology added as a convenient subterfuge? We’ll never know, of course, and that’s part of the fun. Orpheus, Narcissus, Icarus and the rest gave 19th century sculptors and painters the excuse to portray unclad men and youths in a manner which would have been highly suspect—scandalous, even—had the subjects been shown in a contemporary context. In Oscar Wilde’s definition, art reflects the spectator; in Philip Core’s definition, camp is a lie which tells the truth. Camp art, therefore, can tell a truth about the artist whilst reflecting the concerns of the spectator. As it turns out, this work by Henri Peinte (1845–1912) had its delights, camp or otherwise, concealed by a prudish sheet of cloth when cast in bronze, a common fate of reproductions intended for home display.

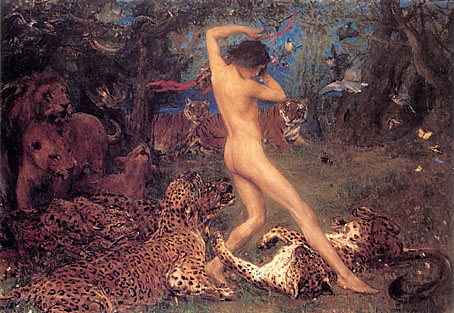

Orpheus by John Macallan Swan (1896).

The Encyclopaedia Orphica collects many of the numerous representations of Orpheus, including this equally lithe depiction by John Macallan Swan (1847–1910) with a pose reminiscent of Peinte’s sculpture. Swan’s painting of the poet charming the savage beasts combines two of his recurrent themes, wild cats and unclothed males. Was he another Uranian with a camp sensibility or is this mere academic innocence? Whatever the answer it’s easy to see why Jean Cocteau—who once said “I am a lie that tells the truth”—made Orpheus his pagan saint.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The gay artists archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Antonin Mercié’s David

• Reflections of Narcissus

• Narcissus

• La Villa Santo Sospir by Jean Cocteau

Tite Street then and now

This LIFE magazine photo of Oscar Wilde’s home at 34 Tite Street, Chelsea, is fascinating for Wilde aficionados in being a far more detailed view of the “House Beautiful” exterior than one ever finds in books about the writer. No information as to when it was taken but from the look of the print it was probably some time just before or after 1900.

Google Earth lets us examine Tite Street as it is today, with Oscar’s house looking relatively unchanged aside from the blue plaque which informs people that he once lived there. What you can’t see in this picture is the opposite side of the street which now contains a particularly dreary housing development from the 1960s. Oscar and his contemporaries in the area—many of whom were artists—wouldn’t have been impressed at all.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The Oscar Wilde archive

Wildeana

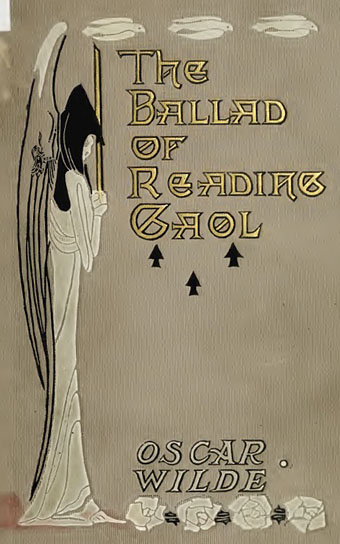

The Ballad of Reading Gaol (1907).

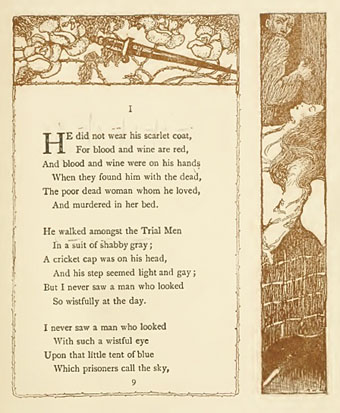

I finished reading Neil McKenna’s excellent biography recently, The Secret Life of Oscar Wilde, a book which makes an ideal companion to Richard Ellmann’s 1987 life of Wilde. Whilst reading about the two trials I remembered that among five pages of digitised Wilde volumes at the Internet Archive there’s a 1906 book, The Trial of Oscar Wilde: From the Shorthand Reports whose contents are what you’d expect from the title. Browsing through the other files there revealed further items of note such as this edition of The Ballad of Reading Gaol published a year later and illustrated throughout by J Latimer Wilson. The page layout of text plus a narrow picture is uncommon, and from the date of publication it’s interesting to see that despite Wilde’s shattered reputation there was still money to be made printing his books.

The Ballad of Reading Gaol (1907).

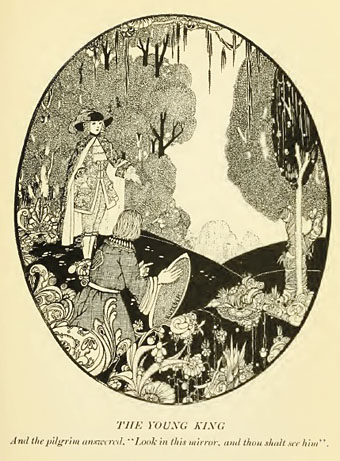

Among the other volumes are two finely illustrated editions of his short stories. The edition of A House of Pomegranates below comes with drawings by Ben Kutcher, an artist about whom I know nothing other than his style is very similar to that of the great Harry Clarke. The introduction is a surprise, a serious appraisal of Wilde’s life by HL Mencken who admired the way the author stood against the prevailing morality of the day. There’s also an edition of The Happy Prince and Other Tales from 1920 illustrated by Charles Robinson.

The House of Pomegranates (1918).

These books are mainly of note for their decoration, however. Of more interest to Wilde enthusiasts is a first edition of Robert Hichens’ The Green Carnation from 1894. Hichens was a friend of Wilde and Lord Alfred Douglas and, according to McKenna’s book, a fellow Uranian (ie: gay) who knew the pair well enough to be able to pen a scandalous roman à clef based on their relationship, helping to confirm for public opinion much that was suspected about Wilde’s outrageous lifestyle. Both Wilde and Douglas disowned Hichens and repudiated the novel but, coming a year before the Queensbury libel trial, it did neither of them any favours. Those curious to read the exploits of “Esmé Amarinth” and “Lord Reginald Hastings” may download a copy here.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The Oscar Wilde archive

• The book covers archive

• The illustrators archive

Salomé scored

Alla Nazimova as Salomé (1923).

I wrote a while ago about Alla Nazimova’s luscious silent film production of Oscar Wilde’s Salomé, a suitably Decadent affair with an allegedly all-gay cast, and costume and stage design based on Aubrey Beardsley’s celebrated illustrations. The film is currently touring England and Wales with a new score for four musicians by composer Charlie Barber, an extract of which can be heard here. I like the Middle Eastern sound of this, a shame the film isn’t coming to Manchester.

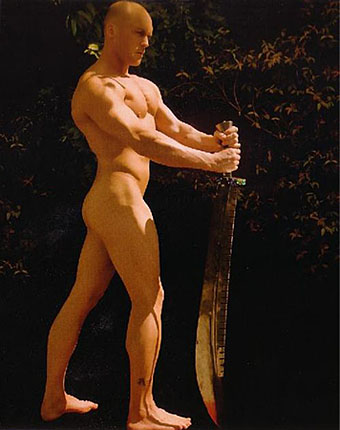

By coincidence, artist Clive Hicks-Jenkins sent these photos of an impressive Duncan Meadows and his equally impressive sword as additions to the burgeoning Men with swords archive. Meadows is shown as the executioner in a Royal Opera House production of the Strauss opera, appearing at the end of the drama bearing the head of John the Baptist. Given the way that Salomé’s body has always been the focus of attention in this story, Meadows’ appearance makes a striking change, one which Wilde himself might have appreciated.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The men with swords archive

• The Salomé archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Equus and the Executionist