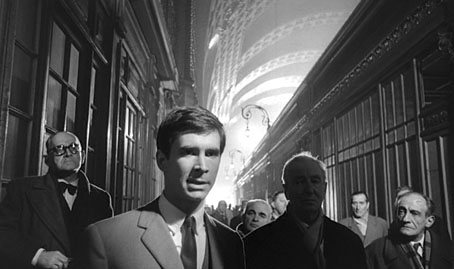

Kafka (1991).

This week I completed the interior design for a new anthology from Tachyon, Kafkaesque, edited by John Kessel and James Patrick Kelly. It’s a collection of short stories either inspired by Franz Kafka, or with a Kafka-like atmosphere, and features a high calibre of contributions from writers including JG Ballard, Jorge Luis Borges, Carol Emshwiller, Jeffrey Ford, Jonathan Lethem and Philip Roth, and also the comic strip adaptation of The Hunger Artist by Robert Crumb. When I knew this was incoming I rewatched a few favourite Kafka-inspired film and TV works, and belatedly realised I have something of a predilection for these things. What follows is a list of some favourites from the Kafkaesque dramas I’ve seen to date. IMDB lists 72 titles crediting Kafka as the original writer so there’s still a lot more to see.

The Trial (1962), dir: Orson Welles.

Orson Welles in one of his Peter Bogdanovich interviews describes how producer Alexander Salkind gave him a list of literary classics to which he owned the rights and asked him to pick one. Given a choice of Kafka titles Welles says he would have chosen The Castle but The Trial was the only one on the list so it’s this which became the first major adaptation of a Kafka novel. Welles always took some liberties with adaptations—even Shakespeare wasn’t sacred—and he does so here. I’m not really concerned whether this is completely faithful to the book, however, it’s a first-class work of cinema which shows Welles’ genius for improvisation in the use of the semi-derelict Gare d’Orsay in Paris as the main setting. (Welles had commissioned set designs but the money to pay for those disappeared at the last minute.) As well as scenes in Paris the film mixes other scenes shot in Rome and Zagreb with Anthony Perkins’ Josef K frequently jumping across Europe in a single cut. The resulting blend of 19th-century architecture, industrial ruin and Modernist offices which Welles called “Jules Verne modernism” continues to be a big inspiration for me when thinking about invented cities. Kafka has been fortunate in having many great actors drawn to his work; here with Perkins there’s Welles himself as the booming and hilarious Advocate, together with Jeanne Moreau, Romy Schneider and Akim Tamiroff.